The Ballad of Harlan County

By Elyssa East

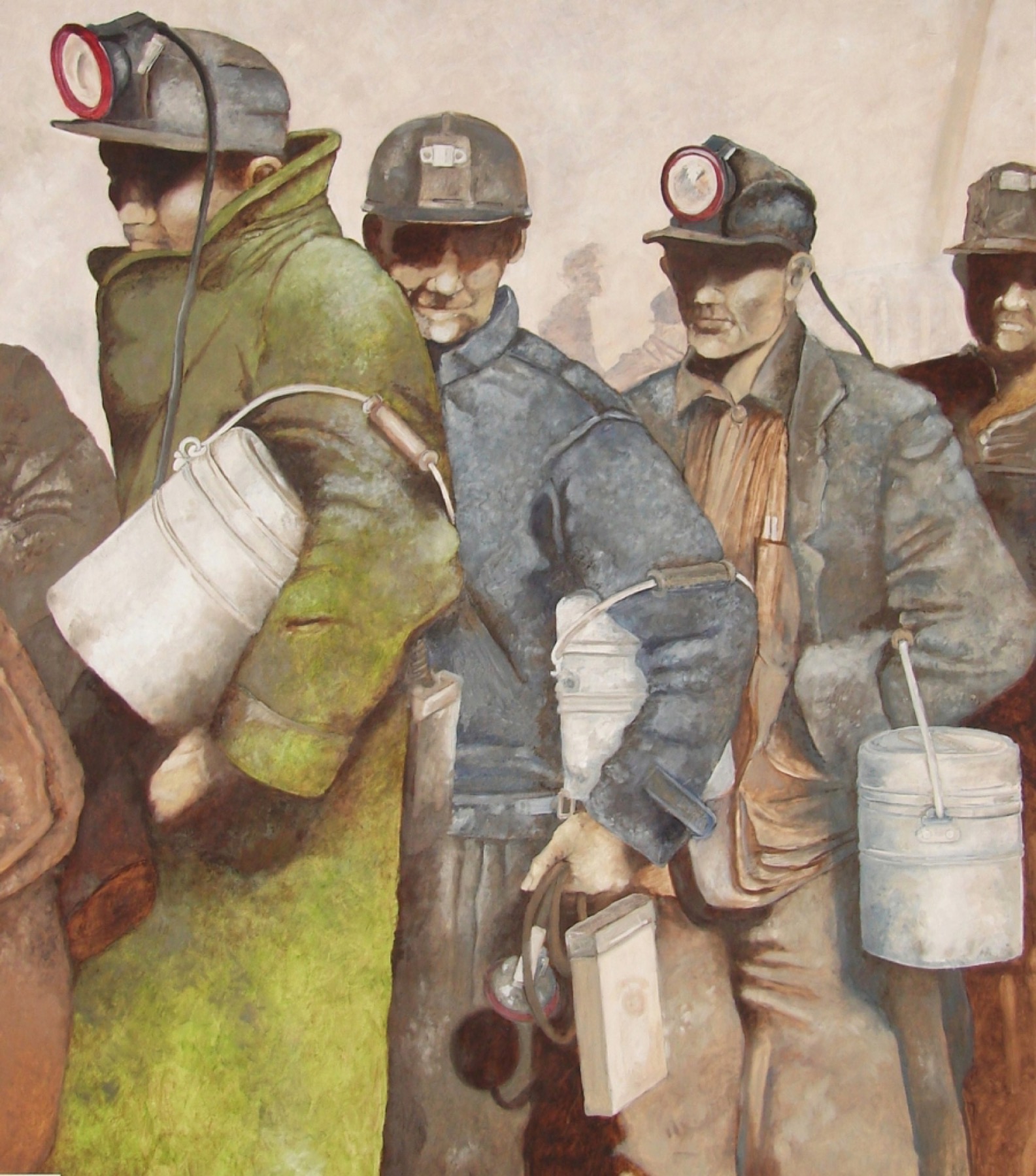

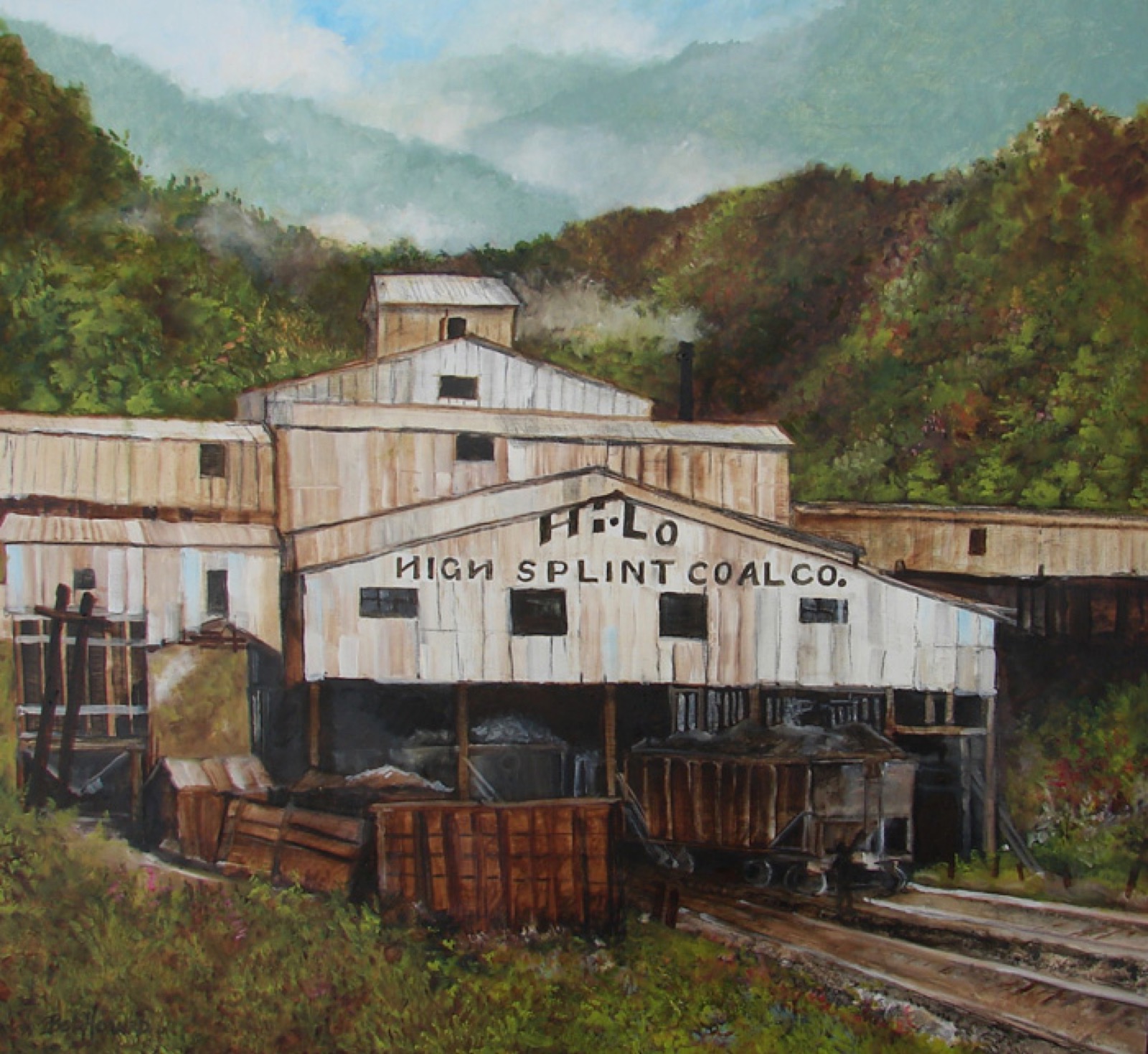

Paintings by Bob Howard

PRELUDE: THE VIEW FROM BROOKSIDE

Mud sucked on my boots. Runoff flowed around my feet, gentle but quick. I was climbing the mountain of my relatives’ former coal mine in Harlan County, Kentucky, walking the land where my grandfather worked for nearly forty years. Brittle vines covered the old office building, the commissary, and the beer hall, which looked as though they could double as a movie set for a Wild West ghost town. This mine, called Brookside, attained national notoriety in the early 1970s after my family sold it to Eastover Mining, a subsidiary of Duke Power, one of the country’s largest energy corporations. Harlan had long been infamous for labor disputes and family feuds, but shortly after the sale, a protracted labor strike was captured in the 1976 Oscar-winning documentary film, Harlan County, USA. This history of hardship and strife seemed distant as I ascended the hill on a quiet day but for the early March breeze riffling through shrubs, and the rasp of silicosis that has blackened Burchel Nolan’s lungs.

Nolan, age seventy-one, is a retired miner. He is easygoing for a security guard and handsome in a salt-of-the-earth way. Today he wore jeans and a navy hooded sweatshirt, with his neatly trimmed silver-white hair tucked under a Tractor Supply Company cap. He was allowing my cousin Elizabeth Jennings and me to tour the mine property. I was a bit concerned that my request to get out of his SUV would get him in trouble with his bosses at Manalapan and Nally & Hamilton, the companies that currently own Brookside and its equipment, though the tipple, the last part of the mine to operate, shut down three years ago.

My need to walk this land felt like a hand at my back, pushing me ahead of Nolan and Elizabeth and past the two deer that stood to the side of the rutted road. My Howard grandmother’s ancestors were among the first white settlers in Harlan. I not only craved the chance to view something close to what they might have seen in the late 1700s, but twelve years had passed since I last visited this place—I needed to make sure that the mountains were still here, that they had not been ground to nothing, their coal stripped off for points afar, the land and my family’s history going right along with it to power the iPhone that I worried like a rosary in my hand, a modern holy thing.

I attempted to capture a panorama with my phone as the light broke through the clouds, Jesus-ray style. Black Mountain, Kentucky’s highest peak, tops out at 4,145 feet, marking the edge of Harlan County and the Virginia border to the east. Pine Mountain stood tall to the north; to the south was Cumberland Gap, across which Daniel Boone led settlers. But these rugged peaks were either washed out on my screen or out of view altogether. The county’s communities, most of which are former coal camps snuggled into the mountains at elevations as low as 1,191 feet, were obscured by the Clover Fork valley’s deep hollers and folds, except for Ages, which was visible just across the way beyond the mine’s rusted-out tipple. The nearest interstates were about sixty-five miles away in opposite directions, adding to the mine’s aura of isolation.

This was my third trip to Harlan. I’ve lived in New York City for fifteen years, but my mother was reared here at Brookside, in frugal comfort in a Sears-kit house. She lived across the railroad track from the mine and camp where her father worked for his uncle Bryan W. Whitfield, owner of the mine. Uncle Bryan was later succeeded by my grandfather’s cousin Bryan W. Whitfield II, who sold the mine to Eastover Mining Company on the day I was born three hundred miles to the south: July 25, 1970.

I grew up far from the world of Harlan, Kentucky, and far from the wealth of my coal-operating Whitfield kin. My mother was shipped off to finishing school in 1951 at the age of sixteen and never lived in Harlan again. In choosing my handsome preacher father for a husband, a man whose harsh Depression-era Georgia tenant farm upbringing was closer to that of a coal miner’s than to that of my mother’s company family’s, she had married down in her relatives’ eyes. Her immediate family’s occasional subtle cues that my siblings and I were fruit from a lesser tree were rarely lost on me, but her father and his Whitfield family were almost always warmly affectionate. What was lost on me: the wealth and power of these coal-operating relatives.

Thanks to my mother’s talent for saving her piano-teacher salary—and some help from my maternal grandparents—I was able to attend an exclusive Atlanta private school, where my friends were picked up in Mercedes and BMWs and whisked away to expansive Buckhead mansions. I was picked up in a Chevrolet station wagon or, to my profound embarrassment on the rare occasion that my father arrived, a Chevrolet pickup with a hot-tar kettle for roofing attached to the back. We went home to a leafy suburb that frowned upon my father parking his truck in front of our house (he rebelled and built a special strip alongside the driveway for his pickup). My father, the only college graduate among his nine siblings (as I am the only one among my parents’ four children), had eventually grown tired of being poor and left the church to go into business as a roofing contractor. He roofed housing projects across the state of Georgia—projects where he often went to live, and where my mother, brother, and I sometimes spent weekends. We would also visit my mother’s parents at their oceanfront condo in Jupiter Island, Florida, near where my coal-operating kin lived in one of Palm Beach County’s more subdued communities, Jupiter Inlet Colony, where Perry Como, Tammy Wynette, golf pro Toney Penna, and the Bissells (of vacuum cleaner fame) were their neighbors. Perhaps it was the brilliance of the Florida sunlight, or the way the air could feel like a steam bath even indoors, but my relatives’ wealth seemed dreamlike and unreal—almost a fiction—though I saw it with my eyes in the oil portraits that adorned their walls and felt it with my hands when I fingered their silk-covered antiques. It wasn’t until a Rolls-Royce sat in one of their garages that I fully comprehended the truth: they were indeed quite rich.

When my parents divorced, I had to pick sides, and I chose my mother’s, as most children do. Still, this decision exacerbated how torn I was between yearning to belong to her rarified kin and feeling outrage and compassion for the struggles and hardships I witnessed in my father’s family, to whom I am equally loyal. My father was born into a life of backbreaking farm work raising and picking cotton and grew up wearing clothes made from feed sacks. Now, he owns and lives in a rural Georgia motel that caters to low-income people who don’t fit into public housing for a variety of reasons, ranging from addiction to their status as seasonal workers. He treats them all as though they are family, but he also rents rooms by the hour.

For years, I fought bitterly with my father, who was often harsh to the point of being cruel, but now he has mellowed with age. At times, I preferred him to my mother for his ability “to be real,” as I put it as a teen. Alternately, I would go through phases of favoring my mother, who is undeniably sweet, and savoring the comforts of her world. Today, she lives in the same Atlanta suburb where I grew up, in a small tract home full of her own silk-upholstered antiques. My maternal grandmother was the last of my grandparents to die, in 2001. Shortly thereafter, I got proof that she didn’t approve of me, as I had always suspected; in the early 1990s, I had become increasingly outspoken about environmental and liberal causes, and had cut off all my hair, striving to be Sinéad O’Connor–chic. At her apartment, I found photos on display of all her grandchildren and great-grandchildren—all except for me.

As I walked toward Nolan and Elizabeth, who were already heading to the car, I set my back to these thoughts and the surrounding peaks. Nolan turned the SUV around at the slagheap and we descended over road ruts to the mine gates. It was time for Elizabeth to leave for work at her family’s firewood-packing business, which they started to help improve Harlan’s economy after coal’s collapse. Initially, they sold candles to fund raise for community members who couldn’t pay their electric bills but quickly realized this was just a Band-Aid. Then the firewood-packing business was born, using wood that wasn’t of high enough grade for lumber.

Elizabeth and I are the same age and share the same given name. I thought of us as the two faces of Janus—she looking toward Harlan’s future and I looking to its past, two members of a generation trying to make something of our respective Harlan legacies.

PART I: BETWEEN DAYLIGHT AND DARK

Harlan remained a rough frontier well into the early twentieth century. In its 1889 coverage of a notoriously cold-blooded feud concerning the Turner and Howard families (both of whom happen to be my ancestors), the New York Times wrote: “The country is wild, and the whistle of a locomotive has never been heard by many of the inhabitants.” At the time, the county had a population of about six thousand. Harlan would have likely remained sparsely populated if some of the country’s richest seams of bituminous coal—also known as “steam coal,” which is medium grade and full of a tar-like substance—had not been discovered in its hills. In 1911, the locomotive whistle finally echoed across these valleys, which had been created by the headwaters of the Cumberland River. An illustrated postcard from 1915 shows the town pleasantly nestled in a crook of the river and bears an optimistic motto: Harlan, Ky., “Ain’t What It’s Going To Be.”

Hailing from Alabama, my great-great-uncles Augustus F. and Bryan W. Whitfield were among those drawn to Harlan seeking opportunity. In 1912, Bryan opened Brookside, whose original company name was Harlan Collieries. Augustus developed a mining operation called Clover Fork Coal Company at Kitts Creek, one mile outside of Harlan Town, as locals called the county seat. At its height, the Brookside mine employed close to three hundred men, including my grandfather, who worked as company treasurer.

When Harlan’s coalfield was developed in the 1910s, the rocky terrain made transportation to the mines difficult, necessitating the creation of camps to house the workers. These camps were private property—not public towns, according to Harlan historian Dr. James Greene III. There were close to one hundred mines back then. The largest camp community housed up to ten thousand people.

“It may have been Prohibition,” Greene told me as we sat on an overstuffed couch at the Little Inn, the Harlan bed-and-breakfast where I stayed, “but there was moonshine going all over the place. Then you had the fact that everybody carried guns. They also liked to gamble.” Greene quoted a New York Times story published in 1938: “A Harlan County camp is no weekend resort for sissies.”

During the 1930s, union suppression and strikes led to violence that went both ways and became known as the Harlan County Wars. Eleven deaths were directly linked to those conflicts, during which the National Guard was called in twice. They also inspired a series of vengeance killings, creating a nearly biblical succession of murders in what was already a violent place. (Greene told me that 1920s-era Harlan had the highest murder rate in the country, beating out Al Capone’s Chicago.) My great-grandfather Howard, who was president of a mining rights company, was run off a snowy mountain road in 1947, his car later found at the bottom of a hollow, his body stripped of his wallet and watch. I’ve always wondered if his killing was somehow connected to labor strife.

When the labor union known as the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) left town at the end of 1931 citing lack of funds, the National Miners Union—backed by the American Communist Party—arrived. Most Harlanites didn’t take too kindly to NMU presence; only a few hundred Harlan miners went on strike with the NMU, as opposed to 6,800 who went out the year before with the UMWA. Sheriff J. H. Blair, backed by the Harlan County Coal Operators Association, who counted my relatives among their members, deployed close to two hundred deputized mine guards to snuff out both unions. The nation closely watched this conflict, which drew the attention of writers Theodore Dreiser and John Dos Passos, who eventually came to town as part of the Communist-backed National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners (followed by other left-leaning literati such as Edmund Wilson and Waldo Frank). By the end of the 1930s, the UMWA had established a better toehold in the county. But for each gain the union made, the owner-operators worked harder to drive them out.

Coal mining was America’s most dangerous occupation by the 1970s. Brookside’s rate of disabling injuries was nearly three times the national rate in 1971. The miners had relatively little complaint about their pay; they wanted better benefits and increased safety. But when Eastover took over the mine from my family, the workers didn’t get to choose which union represented them—Eastover opened with the company-friendly Southern Labor Union in place. Just before this contract ran out in 1973, Brookside miners voted to join the UMWA. Eastover refused to sign the contract, so the Brookside miners went on strike.

Back then, Nolan, the security guard, worked for Eastover’s Highsplint mine, located nine miles away from Brookside. I asked him how he felt about the UMWA. “Some wanted it,” he said, noting that he might have, too, but he didn’t like the way people went about trying to bring it in. Nolan, who had a family of four to support, said that he “didn’t want to get messed up in the thing.” But when the Brookside miners moved their picket line up the road to Highsplint, there was no escaping getting messed up in it, which many Highsplint miners resented. It quickly began to seem as though a labor war reminiscent of that of the 1930s was about to get under way.

“It was a pretty rough time,” Nolan told me. “Each side was armed. It could have turned out real bad there, if one shot had been fired. There’s no telling how many guns were out there.” People on the picket lines were not allowed to have them, but guns abounded on both sides. The strike turned into a thirteen-month dispute pockmarked by gunfire. Miraculously, only two people got shot. Tragically, one of them died. Immediately thereafter, federal mediator W.J. Usery Jr. summoned Eastover president Norman Yarborough and Duke Power’s board chairman to Washington, D.C., where they signed the UMWA contract at last.

When I asked Nolan how work today compares to conditions in the 1970s, he said, “Things have gotten way worse.” For roughly a century after the railroad came in, Harlan flourished or suffered according to coal’s cycle of boom and bust; the county’s population expanded or contracted accordingly. In 2008, though, the industry began collapsing. Coal ranks as the largest source of carbon emissions. Increased environmental regulations; the retirement of coal-operated power plants; fracking, which has lowered the price of natural-gas extraction; plummeting coal prices, coupled with the higher cost of mining in Eastern Kentucky; and measures such as the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan, which local Republicans and Democrats alike refer to as the “War on Coal,” have all driven nails into the coal industry’s coffin. Today, Kentucky coal industry employment is at an astounding low, on par with the figures from 1898 (before the railroad came in). The county’s median household income is $25,186, less than half the national median ($53,482). A third of the community lives in poverty; a quarter of working-age residents are disabled. Unemployment has hovered at 13.5 percent, one of the highest rates in the state, steadily forcing people out. The county has lost five percent of its population in the last ten years, as though Aunt Molly Jackson’s “Kentucky Miners’ Hungry Ragged Blues” and the Seldom Scene’s “Leaving Harlan” are playing in the hollows on repeat.

The unions left with the mines. As of January 1, 2015, there’s not a single union coal mine left in the state of Kentucky. “You might describe it as the difference between daylight and dark,” said Nolan. “Back when I was eighteen, you could go any direction you wanted to and get you a job, but now you’re lucky to find one. Now the trains aren’t even running anymore. They ripped up the rails last fall.”

Nolan never wanted to be a security guard, never liked the idea of having to tell people they can’t do this or that. These days, people come to the old Brookside property wanting to hunt or to find ginseng, which they can dry and sell for up to $1,400 a pound. “That kind of shows you where work’s at,” Nolan said. “People are trying to dig roots to survive.”

***

Coal may be dying, but Harlan has recently been thriving in American media. The FX series Justified is inspired by an Elmore Leonard character from Harlan and is partially set in the town. The National Geographic Channel reality show, Kentucky Justice, about a Harlan County sheriff, portrays the community’s very real desperation. Jordan Smith, who grew up singing in Harlan County churches, gave the country a taste of Harlan’s wholesome side during the 2015 season of The Voice. Smith’s win has given the community a much needed boost.

This year also marks the fortieth anniversary of the release of Harlan County, USA. The documentary is a bracing, dramatic David-and-Goliath story about coal miners pitted against Duke Power. (On the ground in Harlan, people largely referred to the company by its local affiliate, Eastover.) The UMWA, recognizing that a local defeat would be challenging in such a steadfastly antiunion place, strategically went after Duke, which helped land the strike on the national stage. Told through the eyes of the miners and their wives, who joined them on the picket line, Barbara Kopple’s film is an intimate portrayal of the miners’ struggle against corporate greed that continues to have resonance today. In 2006, the Chicago Tribune declared that “there have been few better movies about labor struggles before or since.”

The story surrounds the Brookside miners’ efforts to have Duke Power sign the UMWA national contract, as well as the group Miners for Democracy’s attempt to clean up the union after decades of corrupt leadership under president Tony Boyle. (To cite but one example: Boyle had ordered the murder of his 1969 challenger Jock Yablonski, along with his wife and daughter.) These storylines are interspersed with scenes of Harlan’s poverty; discussions of the industry’s risks and hardships, including early child labor practices and the prevalence of black lung; and passages about Harlan’s notorious 1930s.

Kopple took a cinéma-vérité approach to weaving together these threads. The lack of voice over and minimal title cards can sometimes create confusion for the viewer, but the strike is fraught with enough dramatic tension to present a cohesive whole. State troopers line the road as strikebreakers, led by the gun-wielding Basil Collins, cross the picket line. Miners’ wives are dragged off the line and thrown into jail. Eastover president Norman Yarborough steadfastly refuses to sign the UMWA national contract, coming across as stubborn as wood. Collins’s “gun thugs” fire at the miners’ homes. The striking miners travel to North Carolina and New York City to picket Wall Street, encouraging investors to “Dump Duke.” The utterly fearless Lois Scott leads their charismatic wives to keep the cause going back home.

In September 1973, Judge Byrd Hogg, a coal operator in neighboring Letcher County, limited pickets to three per mine entrance, which enabled Duke to reopen Brookside with strikebreakers it imported from Virginia. But the injunction did not apply to the miners’ wives. Scott, whose husband worked at a Harlan UMWA coal mine, located on the other side of the county, lived at least twenty miles from Brookside. But when a friend asked her if she’d be willing to join the Brookside women on the picket line, Scott said she’d be over the next day.

Americans were accustomed to stories of labor strikes in the 1970s, but news of the women’s involvement—how they lay down in the road and were dragged off to jail with their children—set Brookside apart. “Once I got involved in that strike, it seemed like I couldn’t get out,” Scott said in an oral history housed at the Godbey Appalachian Center in Cumberland, Kentucky. In one of the film’s most famous scenes, she pulls a gun out of her bosom. “It’s time for us to get just as violent as they are,” she says to the Brookside Women’s Club, the group of miners’ wives she began to lead. “By God, you fight fire with fire. ”

Kopple came to town because UMWA organizer Houston Elmore invited her, hoping that the cameras would help quell the violence. The filmmaker obliged. She and her crew moved in with miners and became deeply involved in their plight.

In the film, the low-burning tension gradually builds to a raging flame as Basil Collins and his men attack Kopple and her crew, along with the miners and their wives. It’s all too clear that the Harlan County Wars could reignite at any minute. That is, until one night, away from the picket line, when a pro-company man—also known as a scab—murders twenty-three-year-old Lawrence Jones, leaving behind his sixteen-year-old wife, four-month-old daughter, and elderly mother, who collapses with grief at the funeral. The strike is settled soon after, but the UMWA contract quickly expires. The Miners for Democracy leadership negotiates a new contract with a no-strike clause, but few people in the film are happy with this outcome. The documentary concludes with the message that the miners’ struggle is forever ongoing.

***

The first time I saw Harlan County, USA, in 2011, I was excited and a little afraid as I settled into my theater seat at the Museum of Modern Art. I was wary that I was violating the same family code that had prompted my maternal great-aunt to write me off for attending Reed College, a “Communist, leftist, anti-American institution.” My family never forbade me to do much of anything, but I knew they felt that the film was “one-sided,” “a setup,” or “propaganda.” Most of all, they were beside themselves over the fact that they had grown up at Brookside and knew next to no one in the film.

My family is never mentioned by name in Harlan County, USA, but it is alluded to in many passages about the county’s history. Over this they were none too pleased, which poses a problem: I love the film. I was thrilled by its real-life drama and intimate portrayal of the miners’ lives. I will be forever moved by how Kopple ennobles the miners and their wives, who come across as tenacious, fearless, clever, and at times quite funny. I fantasized about meeting the people captured on film; they were heroes to me.

Parts of the documentary troubled me, though. An early scene depicts workers descending into a mine, followed by the title and shots of the Brookside camp and office front porch. My mother long had a photograph of that porch on her dresser: a portrait of my grandfather and his uncle and cousin. Next came a scene of a wizened old man singing and talking about how his boss—presumably the prior owners of the Brookside mine—said his mule was worth more than him. Was this man singing and talking about my grandfather, my grandfather’s cousin, or my great-great-uncle?

In another scene, a woman talks about how all her life she has considered the company as “the enemy,” and how her grandfather suffered from black lung. Because of how the film is edited, one believes that she is referring to the prior owners of Brookside—which means she is talking about my family. This shocked and horrified me. Though I vowed to keep an open mind, I resisted these words with every fiber of my being. I confess, if the mine in Harlan County, USA had no connection to my family—if the story were about a different industry in a different place—I wouldn’t be giving the company side another thought; I’d be ready to see them fall mightily.

But this was my family.

PART II: IN THE MOUNTAINS OF LOST SONGS

Before I left for Kentucky this spring—five years after I first saw the movie—I set up interviews with people on both sides of the conflict, including one man who I was told could speak to the company perspective. He grew up at Brookside and worked for Eastover during the strike. Because the strike continues to inspire so much tension in Harlan, he asked that I not use his real name. I’ll call him Henry.

“There was no truth in that movie,” Henry said over the phone, reacting as though I had passed a rattlesnake through the line when I said I was “a fan” of Harlan County, USA. “Your papaw was a man of the truth and there’s not a bit of truth in that film.”

The intensity in his voice crescendoed, pride and defensiveness coming through loud and clear. Henry told me that, had I just been some ordinary reporter calling from New York, he would have already hung up the phone. He agreed to take my call because he worked for and loved my grandfather.

Hearing those words made me feel like Henry had bitten the rattle off the snake and handed it back as some sort of peace offering. In childhood, my eldest brother collected rattles from snakes. Every so often, in a sweet and wistful state of mind, he would show them to me. I felt privileged getting to touch something so wild and fearsome, and I was reminded of that feeling after Henry’s declaration. I paced my living room, where images of my family sit atop bookcases, including one of my grandfather as a little boy dressed in a sailor suit and giant straw hat, then managed to shakily jot down the words “love” and “your papaw.”

I was curious about Henry’s words but wary of accepting them, reminding myself that I had to keep my own biases in check. But in Henry’s voice I also recognized something of my own fanged passion for the people I love.

“We ain’t all dumb down here,” Henry said, as if only a fool would fall for Kopple’s movie. “And most of us have teeth.”

When I finally met Henry at a fast-food restaurant on the four-lane strip outside of Harlan, I was completely taken aback. I had imagined someone far more hard-edged than the clean-cut preppyish man who sported a V-neck sweater and button-down shirt, appearing like a suburban, golf-loving grandfather. When we greeted each other, he knocked on his very nice teeth, an exaggerated gesture to show me they’re real. He struck me as being like a lot of the men in my family—men whom novelist Tom Franklin describes as “the sensitive guys at the dogfight.”

Henry had arranged for me to meet a group of men who grew up in coal camps and worked at Brookside, Highsplint, and other mines in the 1970s—men who were all on the company side of the strike. Like Henry, these men were now in their sixties and seventies, and retired from the mines but still working in a variety of capacities, from doing occasional contracting jobs to volunteering in the community. (Most every able-bodied person I met in Harlan was either still working, or yearning to work; hard work defines this place.) These so-called scabs were willing to meet with me, though most asked to remain anonymous for fear of stirring up trouble.

My visit fell during the week of Super Tuesday, and the men chorused over cups of coffee about the Detroit GOP presidential debate (“I’ve been at rooster fights that weren’t as entertaining as last night”) and the community’s demise. (“It happened so quickly and suddenly it takes your breath away. We’re left here trying to figure out what we’re going to do. That’s still to be determined as we sit here today.”) When I asked the men if I should refer to them as scabs, or if they preferred a less pejorative word for people who stand on the company side during a strike, they just laughed. “It’s okay,” one of them said. “You can call us scabs.” They had no problem with the term whatsoever.

It seemed as though all of Harlan comes to this restaurant, including union men and women. They gather every day, though the scabs mostly leave right around the time the retired union men arrive. That’s not to suggest that the mood was tense or unfriendly; it felt like changing shifts. I watched it happen three days in a row. One day, the scabs pulled out guns and placed them on the table. That was just to razz me in good fun, a show of Harlan County’s enduring frontier spirit.

“I’m definitely not in New York City anymore,” I said.

“That’s right,” one of the scabs replied. “You’re safe here with us.”

At the restaurant, I sat quietly to listen and learn; I hadn’t come all this way to argue or seek validation for my beliefs. The scabs discussed the strike and Harlan County, USA interchangeably—and registered plenty of complaints about the film. A common refrain was that it was misleading.

“That strike was about Brookside, but most of the movie was filmed at Highsplint and over in West Virginia,” said one man. “The people in the movie didn’t work at Brookside. The people that was on strike—the people that was on the picket lines—didn’t work at Brookside. The union was paying people to get up on the picket line. There was janitors up there from the school.”

The other men chimed in. “They went around and showed the most dilapidated houses you could find. But there was some on that picket line that had nice homes and nice cars and nice everything. They didn’t show that.”

“I had just as much right by law to work as they did to picket.”

“I was trying to get a college education, so I was on the side of the company. I was trying to work my way out. . . . I had to get on to college. I had to get on with my future. I had to work where I was going to get work and I didn’t see nothing wrong with that.”

“If it hadn’t been for Eastover I wouldn’t have the life I have today.”

“There was too much intervention for it to be a true documentary. It was a reality show.”

“People wanted to just get through that strike. They didn’t want to make a lot of enemies because you might have to marry into their families.”

“The real story is people coming in here and stirring up controversy. Then they leave and we’re left with all this animosity.”

“The news media wants to push us down and that’s why I hate the news media; they write very few good things about Harlan County.”

“I’d give anything to go back down there in those mines.”

“Same.”

A few months before I left for Harlan, news broke that the United Kingdom’s last deep coal mine had closed, a momentous event signaling the end of a centuries-old industry (think of all those Dickens characters). I sensed that everyone around the table knew that nobody would be going back down in those mines anytime soon.

Henry reminded me again that he didn’t want me to use his real name. “All this turmoil happened in Harlan County in the early seventies, and right now there’s some people who are just beginning to speak to me,” he said. “There’s people that still hate me. How deep this thing runs you have no idea.”

He continued, “One of those guys—he was on that side and I was on this side—got saved. Both of us got saved at about the same time. Me and him put it behind us. You have to forgive, but a lot of people don’t forgive. I still see people and they turn their head and walk away from me. It’s because of that strike.”

“Some people hold grudges their whole life,” said one of the scabs.

“Some people hold grudges,” echoed Henry. “That’s right.”

***

“No one ever gets Harlan right,” is a lament I have heard from my Harlan relatives all my life. I call it “The Ballad of Harlan County.” If it had a chorus, it would be about how Harlan and Appalachians are represented to the rest of the world—as uneducated, shiftless, and toothless. And how people here see themselves—as hardworking folk, whether rich or poor, who have a singular culture and history but who are weary of being told they’re not like the rest of us, even while they are exceedingly proud of what makes them so unique. My Whitfield family and the scabs give Harlan County, USA its own special verse.

During my week in Harlan, I pieced together that this locals-versus-outsiders disconnect is more than a knee-jerk reaction. It’s due to the loose handling of facts that frame the strike at the beginning of the film. For Harlanites on the company side, this undermines the documentary’s integrity and leads them to question its larger takeaway.

Take the opening scene, when miners descend into a mine. This mine is Cranks Creek, not Brookside, a point over which I’ve heard my share of fuming. Right there, the film loses some Harlan people. This distinction doesn’t matter to most viewers, of course—it never mattered to me—because we are not attuned to the hyper-local sensibility that is so strong in a place such as Harlan.

Next comes Nimrod Workman, the miner and singer whose story and song make for an incredibly affecting moment. Workman’s scene falls immediately after a close-up of the Eastover office front porch, a filmic gesture implying that we are zeroing in on a specific strike in a specific place. When I first saw Harlan County, USA, I was deeply moved by Workman, whom I had assumed was talking about my family. I later learned that his scene was filmed in West Virginia, where he lived and worked.

Barbara Kopple never responded to my requests for an interview, but I did talk to Anne Lewis, associate director of Harlan County, USA. After the strike, Lewis married Jerry Johnson, one of the striking coal miners depicted in the film. She went on to live in the region for twenty-five years, making films focused on social and environmental issues with the renowned regional media and arts center Appalshop. Lewis described Workman as being “expressive of the region as a whole” and explained that this kind of generalizing is not unusual in documentary. And while I see her larger point, I still find it misleading.

Moments after Workman’s scene, a woman (who turns out to be Lois Scott’s daughter) describes the company as “the enemy.” I had always presumed she was talking about my family’s company, but her grandfather worked at a mine thirty miles away from Brookside. In fact, “the enemy” she described was a very different mine owned by a large corporation.

My cousin Elizabeth had an even more powerful reaction to this scene. “My grandfather went into the mines with his men every day and he died of lung cancer,” she later wrote. “How can we be the enemy?” There were plenty of reasons why the Whitfields could be the enemy—a point I knew my cousin also understands—but Harlan’s mines were not all the same.

The film also has a segment on the use of “breaker boys,” or child laborers who picked slate from coal. But this practice was primarily limited to anthracite coal mines in Pennsylvania—Harlan’s mines contain a softer grade of coal. Though I did meet a miner who labored in Harlan’s mines as a child, Henry was adamant that children never worked in the Whitfield mines.

“For me,” said Lewis, “right at the beginning of the film you’re kind of dealing with the broader picture and then narrowing in.” The intended broader picture is the greater American coal industry, the “USA” in Harlan County, USA. But this is not made explicit, and it grates some locals. When images of the Brookside camp are cut with ones from a welfare camp that is in far worse shape, their distrust of the film is solidified.

I met many people who were on the Brookside picket line, and they would swear on a Bible to the film’s accuracy—though some do note how the sequencing of certain events was changed, which allowed for the creation of a story arc. As for the scabs’ “reality show” comments and remarks about people being from elsewhere, labor strikes are a heightened form of grievance with their own theatricality. They are also dependent upon support from people near and far, which explains why folks came from out of the woodwork to stand with the miners. There is no arguing that the strike footage is what makes the film so enduringly powerful, a great cultural and historical document, and an incredible nonfiction film.

I won’t deny the coal-mining industry’s dark side, the fact that Harlan’s poverty is extreme, nor that my relatives were among the county’s staunchest union-haters. (Elizabeth told a story of when Hollywood producers came to the Kitts Creek mine in the late 1970s, scouting locations for the film Coal Miner’s Daughter. When they arrived, the first thing my grandfather’s cousin Jack asked was, “Are you all union?” When they answered yes, he said, “Then git the hell offa my property!”) I stand with the filmmakers on their message about Duke Power’s corporate greed. I’m also resolutely on the side of the film’s pro-union stance—I’m a union member myself, at New York University. I am proud of my Harlan heritage, in spite of the history I have struggled to accept, and I am proud of Harlan County, USA. But I also see now why the film is so upsetting to my family. It’s unfortunate because the movie’s takeaway, so widely celebrated elsewhere, is immediately lost on some of the people with close connections to the story—people that it might otherwise reach.

***

Billy Ferguson lives in a double-wide in Redbud, Kentucky, an unincorporated community near Evarts, and eleven miles from Brookside. Ferguson is a pro-UMWA miner who appeared in Harlan County, USA. Unlike many union people I contacted, he was willing to share his experience from that time. (Most people who stood on the Brookside picket line are no longer alive.) To visit him, I drove into the mountains up the Clover Fork valley, where fog smoldered across the hills in ghostly wisps. When I pulled up to his place behind the Black Mountain Elementary School, children were playing across a rippling creek from his trailer, and the school’s American flag flapped in the wind.

Ferguson’s wife, Mary Lou—whose long brown hair and bangs gave her an elderly girlishness—had stood on the picket line with him. She came to the door to greet me. Billy, seventy-two, with stage 4 black lung that requires him to be on oxygen, looked up from his chair by way of a greeting. The many welcoming touches to the Fergusons’ décor—dishes of hard candies, angel figurines, framed prayers written in flowing script adorning the walls—reminded me of some of my father’s family’s and neighbors’ homes in rural Georgia. Though this made me comfortable in an otherwise unfamiliar place, I was all too aware of the fact that my Harlan County identity was as a member of my mother’s side—people who occupied a very different rank.

Billy Ferguson had the thick build of a man who has worked hard his entire life but whose energy has been sapped by illness and age. His pain began in 1983 after a rib roll—a mine roof support collapse—sent a “big old rock” into his back, forcing him into early retirement.

In 1973, Ferguson was working the roof bolt machine at Highsplint, which helps to stabilize the mine roof. He went out on strike with the Brookside miners. When I asked him what inspired him to join the cause, he said, “I was fighting for myself and everybody else. Fighting for my right to have the UMWA, for safety in the mines. It was just ragged and rough and they didn’t care what went on.”

Ferguson and his fellow Highsplint strikers couldn’t receive strike pay, but the UMWA gave them a box of food every week. It was enough to feed the Fergusons and their four kids, ages two to thirteen, until a van concealing a machine gun pulled up to his brother Tommy’s house and opened fire, shooting sixteen holes into the slide of a swing-set Tommy and his wife had just purchased for their children; nine holes into the house; and one into the baby’s swing. No one was hurt. Billy and Mary Lou Ferguson sent the kids up to their grandmother’s place on Black Mountain.

During part of the filming, Kopple and her crew stayed with the Ferguson family “until they got wupped,” Billy said, describing the scene when the filmmakers were attacked. Duke Power “didn’t want that to be filmed,” he said. “They didn’t want to see it published, how people was mistreated. We was treated like dirt. We didn’t have no rights.” Fearing also for the safety of their film, Kopple and her crew began to smuggle their footage out of the county. They were welcomed and cheered on by locals on the union side but harassed by strikebreakers, who Kopple claims once pushed the filmmakers’ car off the road. Kopple also alleges that Basil Collins threatened to kill her. She took some heat from the union, too, which was concerned that she and her crew were getting too close to the miners. After Kopple screened the 1954 film Salt of the Earth, which portrays striking miners in New Mexico—a film that had been blacklisted owing to its Communist leanings—for the miners, the union dropped her funding. Undeterred, Kopple sought new funders on her own.

Ferguson risked his job and his life—“I dodged plenty of bullets, I know that,” he said—to have a better working life for himself, his peers, and future generations. But the strike didn’t improve things for the Highsplint miners who joined Brookside on the line. “After the UMWA got Brookside signed down there, they was gone,” he said. The Highsplint miners lost their bid for the UMWA in favor of the company-friendly SLU.

“Me and them that worked up at Highsplint was good buddies,” Ferguson continued, “but after that strike nobody of them would never speak to each other, never look at each other, nothing else. They all hollered ‘If you hadn’t of talked me into it I wouldn’t of done it.’” As for his non-striking coworkers, men like Nolan who were wary of getting involved, “they said we was trying to push the UMWA down their throats. After it was all over with they wouldn’t speak to you or nothing, neither. We was done dirty and done wrong.”

I asked if he meant by the union or the company.

“Both,” he replied.

Ferguson was blacklisted at other mines. “There we was, out in the cold with no job or nothing.” He worked in logging for a while and eventually had to go outside the county to find mining work, which he did until his accident.

Years after the strike, Eastover’s president, Norman Yarborough, conceded that the UMWA “out public-relationed us all over the place.” The union launched a highly effective national “Dump Duke” campaign urging people to dump Duke stock; they sent miners in their work clothes to the New York Stock Exchange floor. The UMWA spent more than $1.5 million on the Brookside strike, the equivalent of $8.6 million in today’s dollars. Looking at it long-term, it seems that neither side won. Ferguson faced the possibility of losing his black-lung benefit, as did Nolan.

I felt a crushing sorrow as I talked to Ferguson, who more than once came to tears. There was a time when coal miners saw themselves as heroically serving the country. Now, it seems they have largely been forgotten or maligned owing to coal’s environmental impact.

“I loved the mines,” Ferguson told me. “If I could, I’d go back today. I loved to cut that coal. You could make good money. We all got along in the mines; we had fun.”

***

I had heard that the coal miners’ memorials in downtown Harlan listed twice as many names as all of the town’s war memorial statues combined, and I wanted to see for myself. I met Dr. James Greene III, the local historian, in front of one of the miners’ memorials: two tall granite columns engraved with an astounding 1,300 names flanking a center stone of polished black granite.

Greene—who I learned is related to me through my grandmother’s family—served as tour guide as we walked down empty sidewalks. At one point, we ran into Donna G. Hoskins, the Harlan County Clerk, who reminisced about a time when the town was so populous that people had to step off the sidewalk to allow others to pass. It did feel as though the town had gone from Technicolor to black and white since the last time I visited, in 2004. The wind swirled the dust and the leaves at my feet and threaded its way past empty, shuttered storefronts—past the small stone church where my parents were married, past the graveyard tucked behind what used to be my grandmother’s flower shop, where my feuding ancestors are buried.

From a distance, I have long imagined Harlan as a land of mountains of lost songs. Not the famous ones—like “Which Side Are You On?” by Florence Reece, which she wrote in the 1930s after deputized mine guards ransacked her home. Or that lament “No one ever gets Harlan right,” the one I had dubbed “The Ballad of Harlan County.” The lost songs I imagined were altogether different. They were the sounds of coal raining from a conveyer, of a coal car running down the track, of an RC Cola rattling in a miner’s lunch pail, the sound dampened by a MoonPie underneath. These tunes were made from the last breaths of miners crushed by a mine roof collapse and the deathly rattle of black lung. They also included the unwritten murder ballads by all the county’s vengeance killers, including the one who murdered my great-grandfather Howard.

For a week I’d been in this community, having coffee with scabs; visiting my cousin’s home; going to the Clover Fork Clinic in Evarts, Kentucky; copying old newspapers in the public library (which had been posthumously named for Bryan W. Whitfield Jr., though his gift to the library was meant to be anonymous); shopping at Don’s, the locally owned grocery; eating at El Charrito Mexican restaurant; buying notebooks in the aisles of Walmart; calling on miners in their homes; and attending the job fair with a hundred job seekers at the Harlan Center, where the parking lot was filled with SUVs and trucks affixed with “Friends of Coal” license plates (slogan: “Coal Keeps the Lights On!”). At the beginning of my trip, I assumed most of my conversations would fixate on the past—on the strikes of the 1930s and the 1970s, and the local repercussions of Kopple’s film. But a different storyline and song emerged.

“Harlan is on the cusp of a very important time right now,” one of the scabs had said to me. “We’re either recovering, in the evolution to something else, or going to near nothing.” I have heard similar dirges in other single-industry towns where the economy collapsed, in upstate New York and in Maine, at the northern end of this same mountain chain. I’ve walked other empty, nearly desolate downtowns. But to me, Harlan is different.

“Harlan County is a symbol,” said Greene. “It’s a shorthand. When people need to trot out poverty, labor violence, or feudalism, they use Harlan County, and that’s part of our problem here.” Of course, in coming back to follow the trail of this strike and film, I’m yet another outsider mining the very history that the town would like to escape.

I took a good hard look at this ailing place. CHRIST'S HANDS was written in large black letters across a modern brick building. The words KY MINE SUPPLY CO. stood up on the roof of a nearby vintage brick warehouse in white, as if issuing a challenge to the mountains behind it. I thought about Elizabeth and her family’s efforts to improve Harlan’s economy by starting a new business. Like an article of faith, you had to believe in Harlan’s future to see it. I couldn’t see it yet myself. But I knew I didn’t want to come back in a few years and find this place finally, officially gone.

***

Jerry Johnson opened the door of his house in Greeneville, Tennessee, a cozy five-room home he shares with his seventh wife, Marcy, and said: “You made it out of Harlan alive!” Johnson, a retired UMWA Brookside miner (and the ex-husband of filmmaker Anne Lewis), was riffing on Darrell Scott’s song, “You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive.”

We set off in his white Crown Vic for a tour of the Smoky Mountains, which appeared as inviting as pillows stacked five deep on a hotel bed, a sharp contrast to Harlan’s rugged peaks. It was the first time I’d seen the sun since climbing up the Brookside hillside with Nolan and Elizabeth, and I basked in it like a cat, savoring how Johnson’s car absorbed the heat. We drove past meadows washed in golden sunlight and headed into a thick forest where we parked by a stream.

“What you see is the reason why I moved here,” said Johnson, who recently left Liberty, Kentucky, where he still owns property. Before that, he lived in various places around the mountain Southeast, working as a coal miner, an underground union organizer, and a filmmaker.

“I got trout laying down in there if I want to eat one of ’em. I could go up that road there three miles”—he pointed to a trail where two women walked their dogs—“and I’m sittin’ on the Appalachian Trail with shelters where I can camp out. I’ve got a spring up there that’s out of this world and I don’t have to own it. You own it. All the way to New York. This is yours. This is ours.”

Johnson sounded as though he had walked straight out of a Woody Guthrie song. In fact, he was born out of wedlock in Harlan in 1946, raised by his grandmother until he was about seven or eight years old. Then his stepfather, a preacher who handled snakes, said, “Maybe I’ll let him come, he looks old enough to work.” If Johnson didn’t dig enough house coal as a child, which he collected out of abandoned mines, his stepfather beat him with a coal shovel. Johnson’s other childhood line of employment was plowing gardens. “I made ten dollars per garden. That was more than coal miners was making.”

The family lived without running water or electricity because Johnson’s stepfather didn’t want to pay any rent. Johnson turned pensive, speaking of the challenges of his childhood as though he were grading coal—this was like peat, a bit soft; that there was anthracite, one helluva hard rock. “We didn’t have it that rough because we had some hogs and chickens. We had a lot to eat, but we didn’t have enough.” The details of his life were things that could combust inside a person one day. He officially went to work in the coal mines when he was thirteen years old because his stepfather “couldn’t dig enough coal to feed the family.”

Johnson and some friends eventually hitchhiked to Scottsburg, Indiana, where canneries were hiring for harvest season. Up north, Johnson lived under a bridge for a couple of weeks, eating from cans of food that had been “bent up bad” on the assembly line. He sent money home to his family.

Once the canning season ended, he traveled back down the “Hillbilly Highway,” as the route between the highland South and the northern industrial centers was called, for Harlan. He worked in dog hole (or low vein) mines, hauled and sold liquor for bootleggers, and built fires at four A.M. to heat the local schools. (Johnson didn’t learn how to read and write until he was forty years old.) By the time he was eighteen, he was mining coal full time. He worked for my family at Brookside—he described the mine as having been especially dangerous—and then he worked at Highsplint, where he tried to bring in the UMWA until he got fired.

A year after losing his Highsplint job, Johnson was hired back at Brookside—then owned by Eastover. He and some peers brought the company’s age-based discriminatory pay system to the attention of the National Labor Relations Board. Eastover and Duke Power paid a hefty fine and put an end to the practice of paying less to men under the age of twenty-five and over the age of fifty. (My relatives were also guilty of practicing this system.) This was just the beginning of Johnson’s efforts to improve his and others’ lots.

In 1973, he moved into camp housing at Brookside. When he and some other residents approached Eastover’s management about putting in running water so the children could take baths, they were refused. Soon, he was building support for the UMWA among his fellow Brookside miners. “We’d approach people as they were discriminated against. We said, ‘Don’t quit. I’m gonna change things.’” And they did.

Johnson, father of three young children at the time, risked everything to bring the union to Brookside. “When you ain’t got nothing to start with you don’t have anything to lose,” he mused. “I had security. I could survive in those hills. . . . I know every weed in the mountains, even here. You couldn’t starve me to death.”

The Brookside strike and the union changed Johnson’s life for the better—but so did Kopple and Lewis. “I think [the film] saved a lot of people from getting killed,” he said. “It exposed the politics of that county. See, everything in the mountains has always been kept silent about child labor and mine safety.”

Even after the strike’s successful completion, Johnson felt that the system was stacked against him and his fellow picketers. He and others who had been particularly outspoken on the picket line were arrested soon after the strike ended. Their jail sentences lasted just long enough to force them to lose their jobs. Johnson hightailed it out of Harlan and moved to Ohio to work at North American Coal. Lewis joined him and took a job in a sewing factory until they moved back to Kentucky to make films together, including The Mine War on Blackberry Creek, a documentary about a strike at West Virginia’s A.T. Massey Coal Company. (In April 2016, Massey CEO Don Blankenship was sentenced to a year in prison for conspiring to violate federal safety standards for the April 2010 explosion that killed twenty-nine miners at the Upper Big Branch mine.)

“Thank God they signed that contract or I’d probably still be in prison,” Johnson said, speaking again of the strike documented in Harlan County, USA. “Once they killed Lawrence Jones they knew we was gonna kill all of them. That’s the way it was gonna go down.”

I felt a chill. “Them” might very likely have included my relatives. At the time of the strike, Yarborough, Eastover’s president, was living in the house where my mother grew up. My grandfather’s cousin Bryan didn’t much care for his fancy home in Florida, so he was still living next door.

Johnson interrupted my thoughts. “Your family was nice people, but you got to understand—they was coal operators.” I was only just beginning to understand what all this meant, for better or for worse.

He then told me a story about my family I’d never heard before—about my grandfather’s cousin Jack, who was running the mine at Kitts Creek. There had been a strike at the mine in the 1950s. But Jack would not sign a union contract, Johnson explained. “He brought in some scabs. Miners went down there and got him and drug him out of his office and put a tin bucket around his neck like a drum. They gave him sticks and he played that and they marched him to the river and threw him in.”

Something about this story got to me, unexpectedly. It must have been written all over my face, because Johnson said, “They’s a lot better ways to have done that—but that’s what they did. Then he still didn’t join the union. He shut down that coal mine and stacked all his belongings and equipment up and never used them again and never mined coal again in his life.”

***

That chill didn’t leave me after I said goodbye to Johnson. I had Kitts Creek mud on my boots, a red dirt in contrast to the black-brown mud of Brookside. The mud was there because a couple of days before, Elizabeth had taken me on a tour of the Clover Fork mine, where her family now operates its firewood-packing business. When I arrived, the air smelled toasty and warm, like a ski lodge, from the kiln curing wood. It crackled with the sound of logs being cut in the splitter.

Elizabeth showed me the mine commissary, which appeared exactly as it was in 1957 when Jack turned out the lights and shut the door after the strike, never to reopen. A calendar from that year still hung on the wall. Cans of coffee, cracker tins, Radio Girl perfume, dresses with sweetheart necklines, and shoes in their original boxes all sat on the shelves, ready to be sold. The meat and dairy cases stood waiting for someone to fill them up and turn the power back on. The phone book listing my grandparents’ number at Brookside, a long-distance call at that time, dangled from a cord by the telephone. To compare it to a museum would be inaccurate. Rather, it seemed as though the commissary was sitting there waiting for everyone to tumble out of their Studebakers and walk through the door, fresh off the road from the fifties.

I thought again of Johnson’s story about my grandfather’s cousin Jack. It must have been terrifying to get thrown into the river, and it must have been horrifying when my great-grandfather was murdered. Elizabeth later wrote to me: “I think today we use the expression ‘blood, sweat, and tears’ metaphorically, but for the family it was literal. You had to fight to keep what you had at work and maintain a safe home.” We both knew this had to be true for everyone in Harlan, no matter what side they were on. It just so happened that this particular side was our family.

I don’t agree with my family’s anti-unionism, but I was starting to understand how much fear had inspired it. “They say in Harlan County, there are no neutrals there,” Florence Reece sings. “You’ll either be a union man or a thug for J. H. Blair.” But what if a person is both of these things at once, or interchangeably?

Because of my parents’ backgrounds, there has always been a class war raging inside of me, a struggle that I am bound to lose no matter which side I choose. Perhaps that’s why Johnson’s story about Jack haunted me. I kept thinking about being alone at Kitts Creek with just Elizabeth and a handful of employees. I was intensely aware that if someone came upon the place with violent intentions, Elizabeth and I would have been trapped. Thinking about this made my blood start to tell me what my conscience—understanding all that I had come this far to learn—wanted me to deny: that in the face of violence, I would have stood with my mother’s family, even if this meant betraying the very principles that had so long pitted me against them. This didn’t mean that I share this value, but I did share their blood. I had struggled with this crux for longer than I could remember. I knew I would be wracked with grief, whether I stood with these kin or against them.

“The hurts that people put on each other during a strike don’t heal too easy,” said Brookside UMWA miner Junior Deaton. The same holds true for the hurts that can run through a family. Perhaps this was ultimately why labor issues burn people up so terribly, because they always come down to family—the families we’re born into along with the ones we raise, and the brotherhood and sisterhood that work creates for us, especially down in the mines, and for men like Ferguson and Johnson. Forgiveness in either of these realms can be extremely hard won. Though Henry taught me that forgiveness is possible.

***

As I drove to the airport to return home, I looked across the hills and mountains toward Kentucky and thought of something else Jerry Johnson told me. On Decoration Day, the day when visitors replaced all the old flowers on the graves with fresh ones, his grandmother always went down to Resthaven—“the real rich cemetery.”

“She’d take all the ribbons they threw away, and sew them into the most beautiful bedspreads you ever saw,” he said. “She’d sell ’em for about twenty-five dollars apiece. That was a lot of money back then.”

Resthaven is where I went the first time I came to Harlan, when I was nineteen, for my great-uncle General Edwin B. Howard’s funeral. It had seemed like an ordinary cemetery to me until my mother showed me the family mausoleum, a large and elaborate marble structure. My mother was so proud, but at the time I looked at the marble carvings on the tombstones of my relatives, including my great-grandmother—my grandmother’s mother, the woman for whom I was named (and who took her own life)—as little more than monuments to the wealth that separated them from me. Now I knew better.

As I traveled a ribbon of road across northeastern Tennessee, fields and rolling hills spread before me, dotted with barns adorned with quilts. I thought of the ribbons gathered by Johnson’s grandmother, ribbons that were very likely tied around arrangements made by the hands of my own grandmother, who owned the flower shop in town. I envisioned Harlan’s patchwork of people, the fabric of a community being made across two women’s hands, a woman of means unknowingly and inextricably linked to a woman without. And I imagined the blankets Johnson’s grandmother made with patterns of blocks and bright stars, tucked around generations of Harlan’s children whose parents prayed for their safety and their futures.

This story was supported by the journalism nonprofit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.