Listening for the Country

By Zandria F. Robinson

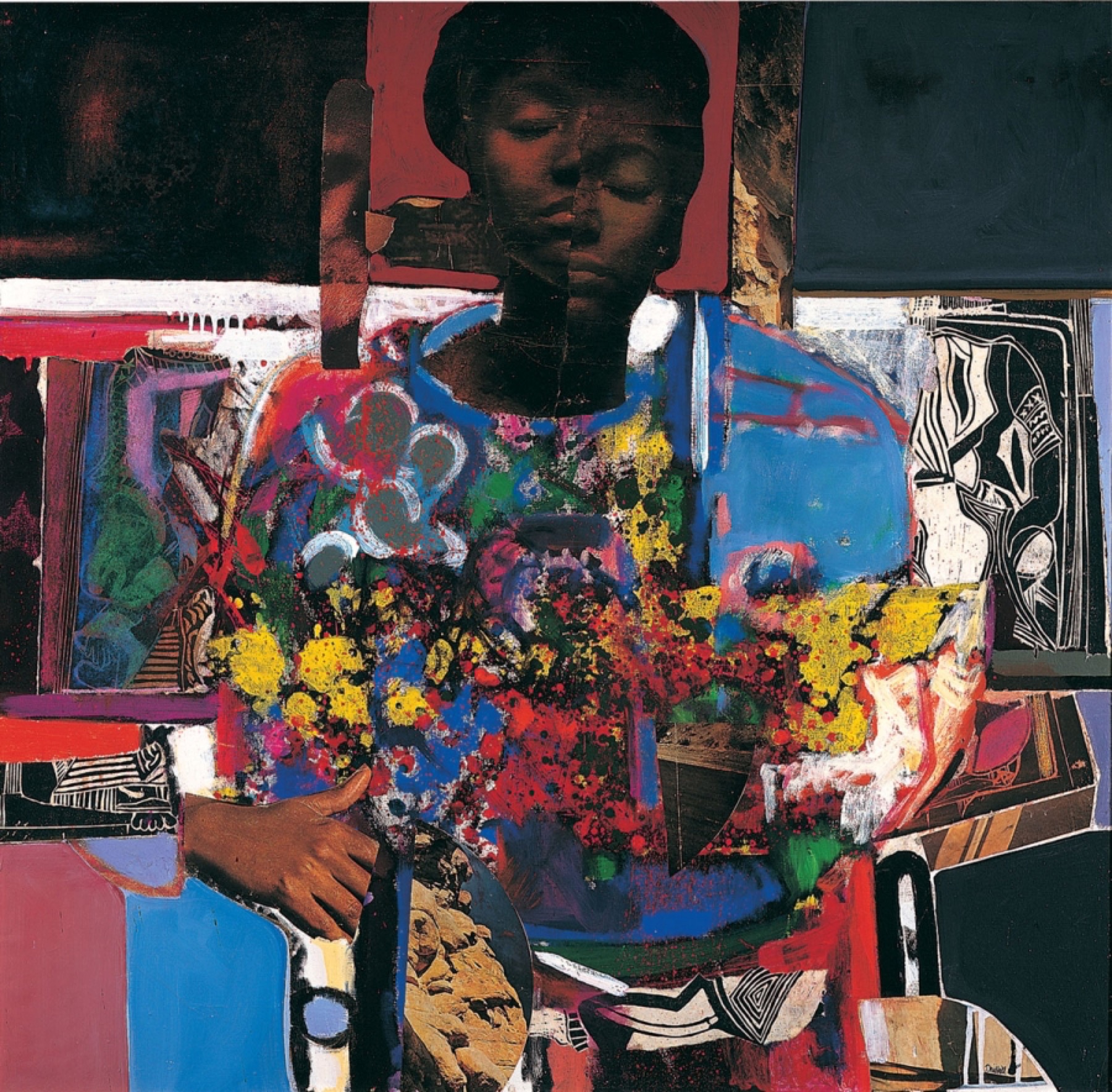

"Woman with Flowers" (1972), by David Driskell. © David Driskell. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

The Shape of Daddy’s Hurt

When I finally cranked the truck, WDIA came in raspy but sure over the insistent roar of the hemi. Together, the engine and the r&b made a Monday-morning kind of sound—time for coffee and work. I adjusted the mirrors, preparing to put the truck in gear. My feet were still swollen from wandering sticky-thighed downtown through packed Memphis parking lots as I looked for the truck in the spring’s first real, wet heat. The swelling was useful, I thought, so my foot could lay heavy on the gas pedal without much flexing and force. I thrust it forward in search of the brake and hit it before I expected; Arthur Lee Robinson was taller than me, but I didn’t have to adjust the seat. In thirteen years, I had never driven his truck, which he bought when he found out I was pregnant with his first grandchild.

Daddy would have fetched his own truck the Friday prior, but he flew away to heaven in the early morning hours of the last day of his jury service. His launching pad had been the sequester hotel on the other side of town, where Shelby County had been holding him and eleven others who would decide if Ricky Patton had murdered Terrance Covington a few Julys back. One juror had been dismissed for discussing the trial. Another had injured himself on the way to the jury box. Daddy’s death, an apparent heart attack from diabetes complications and poor medication adherence, was the third strike. It triggered a mistrial and a brief wave of click-bait infamy, as local and national news-aggregating outlets picked up the story from our paper of record and included all of the facts: Arthur Robinson, 64, was found on the bathroom floor of the sequester hotel by his fellow juror and roommate. The local paper quoted the judge as saying she’d never heard of such an occurrence. She wrote Mama a letter of condolence.

Daddy’s truck was one of those places—like a grandmother’s house, a real and actual soul food restaurant, or a barbershop owned by an older black man who guards the radio by silent threat of the revolver in his drawer next to the good clippers—where one could reliably expect to hear either (and only) 1070 WDIA or 1340 WLOK. It was the other side of sound, the other side of Southern blackness, a steady if muffled undercurrent that persisted and quietly buoyed new generations. I left the radio on WDIA, listening for what he might have heard when he parked his truck in that lot the previous week.

Daddy was country complex. You had to listen for the undercurrent, the Delta lower frequencies, to hear who he was. I knew he wouldn’t be the type to haunt me and offer answers to my many questions from the beyond; he wouldn’t come if I called him forth with my altar of rainbow candles, stones, and cowries. I pictured him in the Hereafter, seated at his table eating a sausage link on a rolled-up piece of white bread, raising an eyebrow in the direction of my summons.

No, Daddy couldn’t be conjured in life, so he certainly couldn’t be conjured in death. Instead, I tried to listen for him, as I had learned to do when I embraced countryness—my father’s, my father’s people’s, black people’s, and my own—as an adult. WDIA. WLOK. The various gospel compilations Daddy had somebody burn onto CDs, now thoroughly scratched from neglect. Songs he sang in the three choirs of which he was a member at St. John Missionary Baptist Church. Field hollers. B. B. King. My investigation was sensory, and I had to just catch the feeling of it, because I could never know for sure. With Daddy, you could only suppose and reckon.

Mama was and is no mystery. As she reminded everyone often, she was born an entire twenty days before Daddy and raised in the city. She said “country” with a deep, monstrous snarl one might use to say “from a can” in reference to vegetables at a family dinner. Country was dirt and rudeness and Delta and blues and double-wides and pig intestines and outhouses and racial repression. It was also violence and hurt and infidelity and excess spilling everywhere and onto everything. Mama was raised in Orange Mound, a historically black neighborhood in the middle of Memphis. She took the city bus while Daddy ran the dirt roads of Glendora, Mississippi, and was baptized in the Tallahatchie. Mama was a teetotaler dedicated to V8 until NPR said it contained too much sodium. Daddy’s whiskey water and pills mangled our home lives until the rehab finally took. Daddy said “nigga.” Mama, “the N-word.” Daddy was Stax and Bobby “Blue” Bland. Mama was Motown. She had preached a quiet and dignified resistance, while I found The Autobiography of Malcolm X in Daddy’s bathroom when I was eleven and read it with baby insurgent interest; I made the tiniest dog ears and mentally charted Daddy’s and my separate progress before absconding with it altogether. Mama went to the doctor more than she went to Sunday service and had the blood pressure of the most unbothered house cat. In the truck, I found at least a month’s worth of Daddy’s diabetes and hypertension medicine strewn about, still in the baggies Mama had carefully packed. Together for more than four decades—most of their lives, until Daddy’s death—my parents were baked chicken and chitlins, wheat and white. Mama was fact; Daddy, feeling. WKNO and WDIA.

Although the Delta was only a ways down Highway 61, my sister and I didn’t visit until we were eight and nine. That was where Daddy’s mama, our country grandmother, Celia Mae, lived, along with the brothers and sisters and cousins with whom Daddy had spent twenty-one years of his life before migrating to Memphis in 1972. He came then to introduce himself to his father, Jack Rose. Granddaddy Jack’s affair with Celia Mae begot Daddy and Daddy’s older brother, his only “whole” sibling. Within five years of coming to Memphis, Daddy had met and married Mama, and we came, starting with me, five years later. In the Delta, we discovered a whole world that we hadn’t seen or heard or known, a world where Daddy had already spent a majority of his life when we came along. A world we could only imagine through stories Daddy told playfully to aggravate Mama; he loved when she fussed and cussed in response. A world we knew from stories Mama told us to cope with hurt and to warn us not to get country dirty. I became an ethnographer in part to understand that world empirically, with facts, so I could translate it for Mama and they could get along better. I always listened, and am still listening, for that world, the formative one that made Daddy. The one that Mama would say made her a widow too soon.

Mama didn’t want that country to get on my sister and me. We knew the mechanics of their country mouse–city mouse skirmishes, deftly navigating around what signified which side. Mama didn’t even want the sound of the country in our house. She was explicit about her disdain for the B.B., Robert Johnson, and Bobby “Blue” Bland blues Daddy played in defiance on our living room radio on the Saturdays he had off. Things that went wrong—Daddy’s alcohol and drug addiction, his infidelities, his son, their hoarding—were country.

Daddy wasn’t warring for our souls, but Mama was. And for a time, she won handily. A black Tiger Mother, she contained us in the relative urban privilege of a two-child, two-parent, two-car home in a lower-middle-class neighborhood in Memphis. We began classical violin lessons before we began elementary school because she loved the sound of the studio strings on Motown recordings. My sister and I were always enrolled in accelerated and gifted programs, and each graduated valedictorian of our respective classes. In our house, getting a B was like not voting—we knew people had died for us to get A’s. My sister grew up to be a Japanese interpreter, and I am a college professor. Our careers are racially and regionally indistinguishable from those of any other children of middle-class Americans.

But country always has a way of sneaking and winning, and with two children, there was liable to be a split decision. Mama’s mama said I should have been named Arthurine because I looked so much like Daddy when I came out. All my life, when I did something that painfully reminded Mama of him—like let money burn a hole in my pocket or shamelessly two-time on a boyfriend—she called me Arthurine with the same kind of malice she said “country.” I thought my sister was the favorite because she was impeccably city. She is measured and reserved and probably still has money saved from childhood. Mama would say I should save like my sister, advising her not to lend me money for the candy lady when I had spent my own. I still borrow money from my sister to this day. Country.

Daddy died a month after Prince, in May 2016. I switched off “Sometimes It Snows in April,” versions of which I had been listening to constantly, and spent the days following Daddy’s death trying to listen for that country. I was trying to find that blues, wanting to know what songs he had sung in the choir, thinking about which were his favorites, wondering if we could have the choir sing one at the service. I wanted my own songs, too, something I could sing to myself to help soothe and release and make sense of things before the visitors started pouring in and I knew I would need to plaster some happy on my face. I rambled in my memory, my few little records, scrolling through my iTunes, trying to find a stick pin in a junk drawer. Asking myself that question so many of us ask ourselves every day—What would Beyoncé do?—I put on Lemonade, preparing for the funeral visitors, cleaning the kitchen and the bathrooms and the living room with “Daddy Lessons” floating through the house on repeat. The song, a reflection on a black girl’s Southern-tough raising, narrates the lessons a Daddy, “with his gun and his head held high,” gives to his daughter before his death. He tells her to take care of her mother and sister, and to shoot whenever trouble comes to town. My Daddy had definitely said “shoot,” too, and I know one time for sure I should have followed that advice. It was the Mama in me, the nonviolence, the city sophisticate, the talk and stick it out, that had made me take more from men than I should have. It’s always been hard to parse which of the country lessons and which of the city lessons I should adhere to and when.

I tried to think of some gospel songs, the kinds that make you holler and cry and reach for God when all those voices rise up together. But I didn’t know any such songs offhand because I’m a heretic and also a cultural Christian fraud—perhaps even a Southern fraud because of this combination of spiritual and cultural heresy. Mama never made us go to Sunday service, only Sunday school, because she didn’t believe fidgeting children should be bothering grown people trying to get the Word. As a child, I read the Bible like I read all other books, hot with King James for thinking he could challenge me with his long-ass book, determined to show him I could read any book cover to cover. The old people at church always said there was magic in the Bible, and I tried to unlock it, sneaking and skipping to Revelations to see who was going to hell in the end. On the phone with her friends, Mama said Daddy needed to get in the Word and maybe he’d stop drinking and drugging and ho’ing. I was confused about how the Word was going to do that for Daddy. Bible men were a mess, constantly being smote and swallowed by fish and cheating on their wives.

At seventeen, I got baptized so I’d be eligible for the church scholarship. Three older black women surrounded me like the witches of Macbeth as I tried to sneak to the car after Sunday school one week. They explained that the deepest understanding of the Word comes after you get saved. Don’t you want to set a good example? Don’t you want to be saved and not burn for eternity? Mama did believe in hell, so I thought maybe I should get saved so I wouldn’t burn. And so I could be eligible for the scholarship. I got it, but then I felt like a fraud because I thought I hadn’t been saved long enough to cash in on Jesus, even for school books.

Mama taught us to fiercely question race, class, gender, our status as Southerners—but she did not want us to question too loudly in church, where she had faced rampant patriarchy and sexism over the years. She was no Bible scholar, but she scoured it for things to help her deal with Daddy, combining its teachings with what she learned in Al-Anon and Overeaters Anonymous, generating her own New Age Christianity before it was hip. This spiritual study and practice helped her suffer the most insufferable humiliations. I thought her marriage trapped her. But she stayed, she said, because the quality of our lives would have been severely diminished if they had divorced. She had not been confident that Daddy would have supported us and feared being plunged into poverty with two little black girls. At the height of his addiction, she managed to keep the lights, cable, and phone on with her substitute-teacher pay, and the violin lessons continued uninterrupted. Still, Daddy once hotwired Mama’s car; another time he pawned our instruments. We had discovered they were missing after we were dressed and greased and headed out the door to play a concert with white people for white people. I’m not sure what Mama prayed for during that time, but I know in those last years with her and Daddy, bitterness and Daddy’s perpetual incorrigibility had made her too tight to pray right for anything. If she was praying, it wasn’t reaching the Lord the way she intended. After he died, she told me she stayed because the Holy Spirit never moved her to leave.

Granddaddy Jack’s wife, Grandma Lula Mae, had welcomed Daddy when he came to Memphis in 1972. At ninety-eight, she still remembers every time she opened her door to her husband’s progeny from other women—she told me she welcomed them all when they showed up on her doorstep. I imagine “welcomed them all” is a euphemism born of temporal distance and dementia. Daddy called her Mrs. Rose, and he reigned as her favorite outside child. When he had his own country child, he brought the baby to Grandma Lula and Granddaddy Jack’s house all the time. Mama eventually put two and twenty-two together and confronted him about it. Mama never said who gave her the math, but Daddy figured out the clue-giving snitch and grumbled about her the rest of his life. Mama often wondered aloud how Mrs. Rose must have felt being put in the position of harboring an outside child. Our brother, whose mother Daddy met in treatment, was nearly two when Mama found out. She told Daddy not to tell us until she was ready.

Eldest children, especially eldest girls—especially eldest Southern black girls—know things they shouldn’t, try to be double agents in grown folks’ fights, and never know that they can’t win until it’s too late. So when Daddy showed my sister and me a picture of a big-headed little toddler boy at a drum set and asked us who he was, I responded without hesitation: “our brother.” Curious about the outside child, I became Daddy’s accomplice. With Daddy, I snuck to my brother’s kindergarten graduation and sat across from my brother’s mother at a Pizza Hut afterward. I was sixteen, and she offered me a car, a Jeep, a country Trojan horse from the outside meant to aggravate the fragile stasis inside. When Mama found out and asked me why were we sitting up at some restaurant like we were a family, I said the woman hadn’t done nothing to me, heaping a hurt on Mama. I wasn’t grown enough then to know just how fundamentally untrue that was.

But I wanted to forge a relationship of some sort with my brother. Our meetings felt like a betrayal of Mama, and they were a country secret I kept well into adulthood. Later, when I was a mother, I coordinated, sometimes clumsily, the times when my brother, my daughter’s uncle, would come to her birthday parties, and the times when Mama, her grandmother, would come. Once I messed up, and my brother and my mother were at my daughter’s birthday party at the same time. Mama told me she didn’t have to come next year.

I didn’t mess up any more timing; over the years, I became a better country accomplice. Four years or so back, Daddy was clearly drinking again, slurring his words and laughing so hard at his own jokes that he might have shook the earth if something deep hadn’t interrupted that joy. I consulted with my siblings. My brother confirmed that he couldn’t help but notice Daddy’s inebriation the last couple of times he had seen him. My sister, home from Japan and living with Mama and Daddy, said she had spied discarded beer cans on the back porch where Mama never looked. I thought he was going to die. I scheduled an intervention with Mama, my sister, and Daddy at my house. Through tears that came from nowhere I told them I wanted them to be happy, together or apart, trying to fix it all right there at the dining room table. Something calmed down after that, and I didn’t see him drunk anymore. As a reward, I sometimes gave him whiskey when he visited.

He had been my accomplice, too, in the way daddies can be on their best days. My daughter’s father, DeMadre, loved him. He always begged Daddy to tell him a story about “a time they whupped the white folks’ ass.” From San Francisco, DeMadre came to the South in the late 1990s after having been wooed by the LeMoyne-Owen recruiter on an HBCU college tour, and I met and started dating him in my second year of college. He wanted to know about the country just like I did. When he would visit us, Daddy would tell a story about when he and his brother borrowed a white boy’s bike with no intention of giving it back and rode it until dark and kept it the next few days, too. “When did you give it back, Daddy?” I would ask on cue. “Shit, when I felt like it,” he would say, and we would try to fill up the world with that small bit of laughter in the context of all that repression. DeMadre, himself an outside child with one other “whole” brother, a fraternal twin, had a fraught relationship with his father. He looked to Daddy as his own. Daddy was an example of the possibilities for outside children, and daddies with outside children.

One August, on the day our daughter turned fourteen months old, DeMadre called my father and asked him to come pick up a two-wheeler he had let us borrow. Daddy was the first on the scene to find him. He talked to the police, and made sure they got DeMadre’s body out after he shot himself. DeMadre had called Daddy so I wouldn’t find him when I got home. In his carefully written note to me, he said I should tell Daddy that he loved him.

At DeMadre’s Memphis memorial, somebody whispered that the coroner had to identify him by his dental records because he had used buckshot instead of duck ammo. I didn’t think this could be true, but everything was so unsure then. I couldn’t shake that nightmare vision out of my head. I finally told Daddy and asked him to tell me the truth. Daddy replied like he had been called to death scenes for terminally sad outside children all his life: “Naw. He jus’ had a li’l hole in his head.”

DeMadre died about a week before school was to start. I was entering the second year of my master’s program at Memphis, preparing to teach my own class for the first time, and starting some fieldwork—and I was scrambling to find care for my still-nursing toddler. Daddy changed his work schedule to keep my daughter on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings that year. Each morning, he took her for a breakfast of grits, sausage, eggs, and toast across the street from where I had moved into student family housing. My daughter had walked on her first birthday but quickly decided walking was overrated. Daddy held her hand and made her walk baby-bowlegged around the family-housing playground until she felt confident enough to do it on her own. She was running in no time. He gave her sips of coffee at those breakfasts, too. “In the country, babies always usta drank coffee to get ready to pick cotton,” he said. You never could tell if Daddy was serious.

When Daddy went to theology school and got a degree, started reading the Bible more than I had as a little girl (and for seemingly religious rather than vengeful purposes), joined Mama’s church and three of its choirs, began leading the Nurture for Baptists group, took over leading the holiday family dinner prayers, and became assistant superintendent of the Sunday school on the fast track to take over as superintendent—I didn’t know if he was playing a major joke on us or if he had seen his life flash before his eyes. He had grown up in church, but, by all accounts, he had hell in him as a child, despite his baptism.

If Mama’s faith had been on a steady utilitarian hum, Daddy seemed to now be really in search of God’s Word and the truth and the light. In his truck I found spiral notebooks full of scripture notes. Mama used to say she wished all that Bible and church would make him a better husband. He was a complicated country contradiction.

Mama was temporarily devastated when I eloped, but Daddy was delighted. He found the whole thing amusing. It had been ten years since DeMadre’s death, and after suffering through raggedy partners that I had refused to marry in the interim, Daddy was glad to have a decent and official son-in-law with whom he could talk shit and fix shit.

The January before Daddy died, it had gotten down to 42 degrees in my husband’s and my house, and Daddy couldn’t figure out why. We had been ordering parts for the furnace, swapping things around, waiting for other parts to come in, and nothing was working. He thought it might be the valve and brought one in from the truck to change it. Our valve was old and stuck, and he insisted on turning the large cracked red wrench himself to take it off. He was tired and had been moving more slowly, as I had commented several times. He said he was all right. But watching him try to get the torque on that thing was torture. I joked, “I been working out, you know, I’m pretty strong,” and my husband nearly jumped in at one point, equally tortured by the sounds of work coming from Daddy’s body. But it finally gave, and he quickly got the other valve on. We went to test the system again, sure we had it fixed. It didn’t work. “Aww, gotdamn,” Daddy said. We trudged back up from the basement. He was so disappointed, and I was far sadder for him than I could have ever been about the cold. He said he’d be back the next day after work.

Exhausted and frustrated that night, Daddy dreamed of his grandmother Rosie Robinson, whose surname her daughter Celia Mae inherited, which Celia Mae gave to Arthur because she was not married to his father, Jack Rose, when Arthur was born. Daddy gave the name to my brother as his first name—a reverse junior. In the dream, Daddy was with his older sister and saw Big Mama—as he called his grandmother—on top of a hill, looking as young as ever. He was scared of Big Mama, subconsciously goading his sister into asking a question that might have earned him a dream whipping. “Big Mama,” she had asked her up the hill, “why’d you discipline him so?” Big Mama responded, “Because the Lord showed me.” He awoke with the answer to the heating conundrum, a temporary solution while we waited on a new circuit board to arrive, and told us about the dream over whiskey in a warming living room after he got the system going.

The next week, he went out and bought Mama all new appliances. They still had the avocado green stove from when they had moved into the house in 1976, and the oven hadn’t worked in months. The refrigerator door had never closed properly since they switched the side it opened on to accommodate Mama’s left-handedness. And the washer had been flooding the kitchen whenever it felt like it. You could hear the steam whistling out of Mama’s ears as she fumed about the money he had spent as well as the fact that he had not consulted with the person who most uses the appliances. He also hadn’t measured the space for the refrigerator, and as a result, Mama repeatedly referred to it as “the big black dick in the living room” until they swapped it out. Mama, the practical one, had never owned a new car or had a car note, and Daddy had been telling people he was going to get rid of her aged clunker and buy her an Impala. It was the car he had when they had first met. He didn’t get to buy her the Impala.

Prince was gone and a month later so was my daddy, but the world did not care—not one bit. It continued on unbothered, the zodiac clicking right on over to Gemini and reminding me that I was still alive, even if Daddy and Prince weren’t, and I would have a birthday soon. Mama and I were sitting at my dining room table planning the funeral program. I asked her if she knew Daddy’s favorite song. She didn’t know, she said, mentioning that she liked “Come Ye Disconsolate,” but that she ain’t want nobody messing up Donny and Roberta. I wondered if I could sing it, but I wasn’t going to have her mad at me because she didn’t think anybody but Aretha and Luther and one of the Temptations could really sing. Funerals are for the living.

Daddy had a blues all his life that I couldn’t begin to know, though I had so desperately tried to understand it as his first-born and accomplice. He sang in three choirs at the church; surely there were songs. What were his favorite songs to sing in the choir? What were his go-to shower songs, or caterwauls, as Mama and my sister would call them? What songs had he stolen away and hummed and moaned in the quiet?

I put on my ethnographer hat and went back to the CDs that I had found in the truck. There was the first album my brother’s jazz fusion band released. A specially burned prerelease of my husband’s hip-hop EP. B. B. King’s greatest hits. Disc 3 of Prism Leisure’s essential jazz collection. The 2010–2015 St. John Missionary Baptist Church—Barron Street, not Vance Avenue—Gospel Choir anniversary CDs. A 2011 St. John Missionary Baptist Church—Barron Street, not Vance Avenue—Male Chorus CD. And CDs with Mama’s left-handed writing on them: three annual compilations she made for everybody she knew at Christmastime with both secular and Christian songs; the soundtrack to The Preacher’s Wife; and a compilation of women singing gospel songs with Whitney and Aretha. There was a CD I had burned for him years back with Bobby “Blue” Bland, B. B. King, and some Lee Williams spirituals on it.

Daddy had given me a list of requests for Bobby “Blue” Bland. “Ain’t No Love in the Heart of the City” was first. Then there was “I Wouldn’t Treat a Dog (The Way You Treated Me),” “Steal Away,” “Three O’Clock Blues” with B. B. King, “I’m Too Far Gone to Turn Around,” “You Did Me Wrong,” and more. When I first saw the list, I thought it was mighty narcissistic of Daddy to be having the blues with all he had done to Mama. But listening to that music in the wake of Daddy’s death some ten years later, I was compelled to consider for the first time the shape of Daddy’s hurt—and his right to it. He had hurt Mama and the rest of us, but I had not given him space to hurt, not about anything, really, beyond a stubbed toe. His upbringing in Jim Crow Mississippi with disappearances and violences and the concomitant beatings from Big Mama Rosie. A missed scholarship opportunity because a racist counselor hadn’t turned in a form. His visit to Memphis that was only supposed to be a stop on the way to St. Louis that turned out to be an entire life and abrupt death. His guilt about what he had done to Mama, or to us. His mama’s death, the only time I saw him cry, and all the other people he loved who had died or gone missing. Having to tell his daughter about the hole in her child’s father’s head. And those women who weren’t Mama. I wondered if Daddy was thinking of them when he listened to Bland sing:

Had they broken my daddy’s heart while he was breaking Mama’s? Did he hear Mama’s city pain in Bland’s declaration that he had a “hole where [his] heart used to be”? Or was he thinking of his own heart, and how he had turned Mama mean? I wondered if Daddy was listening for the country in Bland, or if he just needed someone who sonically and ontologically knew his regret and guilt and sorrow and heartbreak. Like Bland, Daddy had “felt so bad” and found places to “steal away and moan sometimes.” If I couldn’t know where he stole away, I wished I could know what or why he moaned.

To triangulate and make sure my research was robust, I started listening to WDIA incessantly. I listened to the parade of voices, newcomers and regulars, weighing in on the day’s events, half hoping Daddy would call in and say “psych!” and laugh and laugh and laugh until tears came. I tried to recall those snippets of songs I used to hear on the way to Sunday school, the only time Mama would switch from the oldies station to WLOK. All those years listening weekly on the fifteen-minute ride to Orange Mound, and I only came up with enough memory matter to Google two songs. “A witness? Can I get a witness? For Jesus? Somebody know Jesus? Won’t he make a difference in your life?” That one turned out to be “You Brought the Sunshine,” a Clark Sisters song originally recorded the year before I was born. I listened to all of the available versions, watching those four Detroit Clark Sisters singing and shining and glittering with their spectacular hair. Without that AM crackle and on-the-way-to-Sunday-school anxiety, I couldn’t catch whatever it was I was looking for.

The other lyric I recalled was “I lift my hands in total praise to you.” I remembered the song’s concluding chorus of amens because that was the snippet WLOK would play between tracks. Atlanta-born, Chocolate City–raised Richard Smallwood had written that song—“Total Praise.”

I listened to it over and over and over and got nothing.

There was business to tend to. My sister and I were grown daughters for real now, and we made plans and helped Mama make plans like grown daughters do. That Monday, the day after I found the truck, we met with the funeral director at my dining room table. Her wig was a carefully manicured synthetic helmet of sorrow, jet black with blond highlights. Both ancient and from the future, it swooped gently across her forehead, framing her face. I figured she must have worn it to communicate how sorry she was about Daddy’s death.

She knew Daddy and demonstrated how she would pull his face into his signature smile. We were going to put him in a red tie, and the theme color would be red. Mama and Daddy’s pastor was there, too. He pulled my sister and me aside to warn us not to let this light-eyed lady with her Sorrow Wig trick our grieving Mama out of money. He admonished us to tell the lady we only had $3,000. Later, I told Mama what the pastor said, and she said Daddy would have gotten up from the dead and said, “Bitch, why you put me in this wooden box?” if she had given him a $3,000 funeral. She tickled herself with the truth and absurdity of the prospect. There was some longing there, too.

My sister and I worked tirelessly on the program, she on the format, me on the obituary. Mama tried to get the order of the siblings from both sides straight so no one would be offended. She wouldn’t let me put my brother in the obituary, but he was in the list of survivors and in the funeral car, our fragile family making small talk and nitpicking over funeral details. I was a weary country accomplice.

By the day of the visitation, I had cried, but I still had not been carried away like I needed to be to clear my system before the show. Walking into the church, I saw the red tie first. I went straight to the casket. The diabetes got his body. The barber was terrible. They hadn’t cut his nails again. The makeup was too light. They hadn’t pulled the wires hard enough for the smile. I touched the tie, careful not to mess up the delicate but grotesque system that held his body there propped up for us to see. I had cleaned his signature cap—it said rob in white lettering on a black surface with a red rim, something he had specially made with a gift card I got him. I had intended to place it in the casket, but I changed my mind and kept it, withholding it from this body I didn’t recognize.

The break did not come at the wake or the next day at the funeral, not even when the casket was reopened because my “whole” uncle from St. Louis got lost and was late. The pastor said a few words about Daddy, and Mama whispered to us even though she is biologically incapable of whispering. (“He should have seen the hell in him before he got to church every week.”) The pastor then launched into the kind of homophobic and sexist tirade that made me hate the church as a child, managing to condemn Caitlyn Jenner before opening the doors of his Father’s house to receive new members. The choir, sparse because it was Memorial Day weekend, didn’t sing anything of particular note. I was fidgeting for a break, but I would not get it there.

Mama had designated one friend, one church member, one coworker, and one family member to speak at the funeral. She wanted to prevent infighting about who in the family had the most right to speak. There had already been a squabble about who was the oldest of his sisters. To settle the argument, they drew out their driver’s licenses and compared.

The coworker who spoke had worked alongside Daddy for years without knowing his full name; everyone knew him as Rob. A frail man with glasses, he said he had once told Daddy about his rheumatoid arthritis, and how his doctor said he wasn’t going to be able to work anymore before long and that he was going to have to get a cane. Daddy told him, “Get an umbrella.” The man replied that an umbrella was fine for the rain, but what would he do when it was sunny out? Daddy said, “Use it to keep the sun off ya face.” So the man got an umbrella, and held it up for the church to see. With his umbrella cane still raised, he concluded, “He loved his whiskey, and he loved his family. And I’m gon’ miss him.” No one could ever tell if Daddy was serious.

After everyone was gone, when the lights were off, I thought release would come. It didn’t. I just kept listening for things.

What did come was a windstorm that shook the house and knocked down the two trees in my backyard. I heard the crack like lightning and got up from the dining room table and walked into the kitchen in time to see a massive branch fall and take out the east fence. I stood there waiting for the rest. Just take me on out, then, if you wanna, shit. But my daughter screamed at me to move and get to the basement. She had already been upstairs to fetch her baby brother from his crib. I was still staring when she commanded me again: Move, Mom.

No power lines down, no structures damaged but the fence. The second tree had been plain snatched up at the roots like a giant had plucked it up to floss with and dropped it when he was done. There was nothing left but heat, so much sun now where there once had been shade. It hurt. I had grown so accustomed to the shade that I had forgotten where it was coming from all these years.

The last piece of business was Daddy’s car, a red Oldsmobile 98, the same shade as his truck. It had been given to him by his brother, and he planned to drive that car when he retired. He kept it in storage, spending thousands of dollars over the years, awaiting that day. Since he had turned fifty-five, he had been threatening to retire at sixty-two. Mama couldn’t bear the thought of his not getting the full Social Security benefit. Even though she knew he could get the full benefit at sixty-six, she wanted him to wait until sixty-six-and-a-half, perhaps for good measure. Well.

We had to cut the storage unit’s lock because none of Daddy’s three dozen keys fit. I squatted down as far as possible to have enough force to lift the door. Seemed like ages since it had been raised. And there was the car. It had three flat tires and part of the unit’s ceiling had caved in on it. But there it was. Still proud. Hidden away in a tight, musty space and entombed with cancerous stuff crumbling around him, but there he was. Arthur Lee Robinson. There were two air-conditioning motors inside, too. A Mama size and a Daddy size.

I had driven over in the truck, and WLOK was on the radio when I returned to head to the other side of town. I had just left it on in there. “Lord, I lift mine eyes to the hills, knowing my help is coming from you,” said the voices from the speaker. “Your peace you give me in time of the storm. You are the source of my strength. You are the strength of my life. I lift my hands in total praise to you.”

Halfway down Park in Orange Mound, “Total Praise” came on. It finally got through to me—catharsis came so hard and fast I could not see. My eyes were raining and there were no damn windshield wipers. I just pulled in the turning lane and parked and waited for the rain to pass but knew it wouldn’t. There came that chorus of amens, one on top of the other, and I wailed until I was afraid I was being sealed away, too.

Sometimes I’m still there in that lane, facing east, hands lifted, unable to get out and back home to myself until somebody brings the right key.

Daddy liked to tell Mama that when they retired, he was moving them to some land in Mississippi and giving her a truck patch to garden. Mama would balk, saying proudly that all the plants would die if she were in charge. When any of us would sing, he would ask if we sang in parts, though we were all better singers than he was, with or without a choir. He ran us out of rooms with his flatulence and paid us a dollar to scratch his dandruff and a dollar for each A we earned. He always brought money right on time when I hadn’t asked, and we knew he was so proud of us. He loved sausage links and chitlins and peanut M&M’S, and had his absolute favorite—ribs—for his last dinner of jury duty. He loved Mama the best way he knew how. He was sorry he hurt her, though he didn’t ever say so except for with the Bobby “Blue” Bland, and the appliances, and the new car he wanted Mama to have. She finally got it after he died.

Mama still finds things of Daddy’s that she thinks my brother would like, and in my accomplice role, I get them from her and give them to him. Watches, shirts with “Rob” on them, caps. She asks me what my brother has said about these things. She’s said his name or referred to him as my brother more in the few months since Daddy died than she did in his entire life. In the end, Mama did right by Daddy’s son.

I will always wonder what songs of comfort he sang to himself, what he hummed alone before he flew home in the end. “This old world is so lonely. This old town is so sad. This old room is so cold and empty,” Bland had sung. Daddy must have felt so bad. What of his gospel? When he lay on that cold tile to rest and prepare for flight, was DeMadre there with a warm laugh and his own caterwauling, returning the favor? When he at last no longer had to steal away into himself to moan, what was his solace? Did he take his final right to cry? Did he lift his eyes to that hill where he saw Big Mama, knowing help was coming from her, and from the Lord? What did he pray?

In the end, I hope there was a chorus of rising amens to free him, lifting him in total praise for a life well led.

I hope he had all the amens. Amen, amen.

Amen, Daddy, amen.

Amen. Amen.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.