Becoming Integrated

By Frederick McKindra

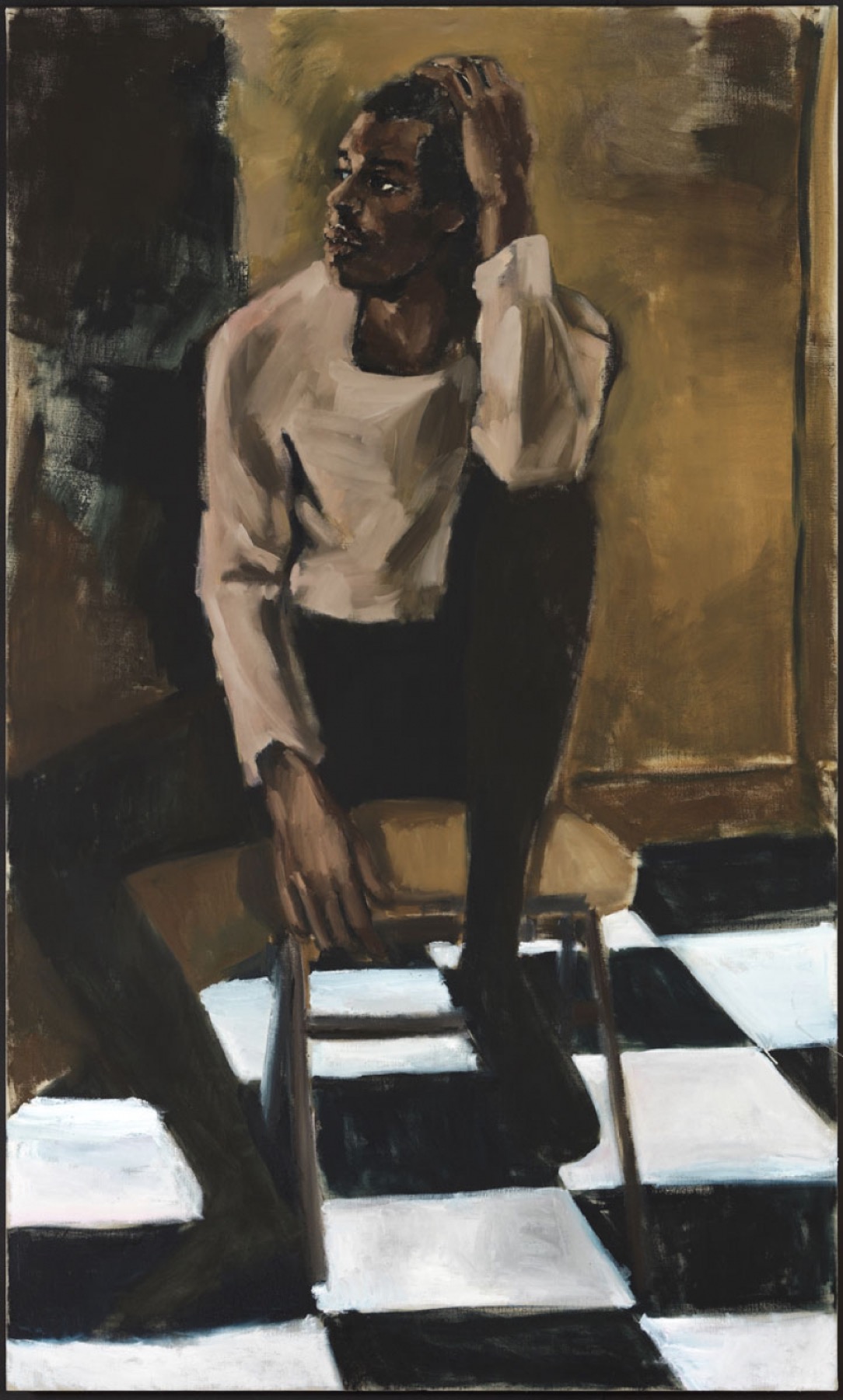

“Medicine at Playtime” (2017), © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Corvi-Mora, London

Trying to achieve black selfhood in Little Rock

In the wake of becoming president of the student body at Little Rock Central High School in 2001, I asked my parents if I could begin twisting my afro—five inches tall when picked to its full height—into dreadlocks. Two years on the school’s student council had diminished my interest in student government, despite now reaching its highest office in advance of my senior year. By then, I wanted to be a writer, and writers were a more disheveled tribe than student government drones. Politics had held much more enchantment for my older sister, who four years before, had managed to achieve one of those august-sounding “Negro firsts” people insert into speaker introductions—first African-American female student body president. Still impressed by the sound of a title such as that, I followed her lead dutifully. Also, I loved my school, and my classmates, most of whom accommodated the restless grabs I made for new accolades, often leaving me too frantic to exchange much more than a grin, a dap, or an affirmation or two.

For days, my father held out in silence at my request. I set myself to researching salons, flicking back and forth the single yellow page that listed all of two natural hair-care shops serving the city, quite loudly, to remind him. (Locs had only just begun their long arc toward assimilation.) Days later, although the Internet speed in our home was sufficient to support email, my dad opted instead to type his response in a letter, which he printed, then tri-folded, then sealed inside an envelope before giving it to me. Therein, he advised me to consider carefully what such a hairstyle might mean to the office to which I’d recently been elected. Given his progressive politics, his response shocked me; it felt like an acquiescence to a convention of respectability I’d long believed beneath him. However, I sometimes suspect that his response grew from an acute knowledge of me at the time. This suspicion stems from what I remember of his tone—knowing, no trace of reluctance—while we argued the topic. He did eventually grant his permission, but only warily—a wariness not of what my hair would be saying, but from whence came my need to say it. He knew by then the way I liked to position myself apart from others, exceptional. He knew I’d become comfortable with the stunts such an identity demanded one make in order to distinguish one’s self and understood that I found them all the more thrilling when pulled for the benefit of a white audience. He suspected, I’m sure, that I intended the hairstyle as such a spectacle, a declaration of defiance that would draw even more attention to me, and to him the foundation under that declaration must’ve appeared flimsy. The hair would say what my grinning mouth and involuntarily nodding head could not: that though I’d now become a representative of an institution, I still held myself apart.

To my father, a career-long community organizer in the Mississippi Delta region, flaunting dreadlocks meant to signify something while enjoying the favor and acclaim of such an office as student body president must have seemed like little more than a hot take, a bluff from a pseudo-radical millennial with too short a timeline in mind when he spoke of “change.” It remains unresolved to me what message he intended to send in that envelope; my wrangling over his intent has long outlived the hairstyle itself. And yet I return to that moment, possessed of so many of the tensions I felt then and still feel—my attitude toward home, community, the South, race. Wondering if those things would define me permanently, or if they could be shucked off by distinguishing myself, or by deciding to leave.

Central, of course, was not the best place to plant and fly a flag of race politics as a mere gesture; it is the cradle of integration, the place where the integration narrative achieved its most evocative display. Another landmark anniversary to commemorate the 1957 integration of the school arrives this year, with all its fanfare and somber recounting of a past both shameful and triumphant. I’ve derived new questions from the integration narratives told about Central in the intervening years, though, pondering now what these kinds of stories have done—and still do—to me, my community, my hometown, and maybe other places like it.

James Baldwin wrote of the power of those narratives, how the image of Dorothy Counts integrating a school in Charlotte, North Carolina, had been the clarion that had reached him in Paris, calling him home. To my mind (and to most of the nation), the photos of Counts in no way rivaled the force of those from Central in September of 1957: the mob of segregationists heckling fifteen-year-old Elizabeth Eckford, whose mouth had always made her seem so vulnerable, whose sunglasses and short-sleeved blouse and skirt and primly curled hair had made her look indomitable and cool despite the terror at her back. That Eckford arrived to confront that horde of segregationists alone because her family had not owned a telephone—and so had missed the change of plans from organizer Daisy Bates for the Little Rock Nine’s entrance to the school—only stoked the sympathy I’d felt first encountering her image in history textbooks and seeing it again year after year (because, in Little Rock especially, the image is inescapable). The Nine were recognizable around the world, had been so almost immediately upon defying both the white segregationists who’d gathered from throughout the state (and indeed the South) to protest their admission and the Arkansas National Guardsmen deployed by Governor Orval Faubus to block their entry to the building. The images of those black teenage Arkansans—Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Pattillo, Gloria Ray, Terrence Roberts, Jefferson Thomas, and Carlotta Walls—parting those white martial forces, both deputized and not, captured the sort of ecstatic surrender one can become entranced by if one is sat before too many civil rights movement documentaries.

I treated the story of the Nine as impolitely as the language above implies, their fear like a trophy, their likenesses too familiar to retain much significance. I read their histories—The Long Shadow of Little Rock by Daisy Bates and Warriors Don’t Cry by Melba Pattillo Beals—and I distinctly remember feeling ashamed for enjoying The Ernest Green Story, a 1993 made-for-TV movie, as much as I did. I blamed that on Disney, who’d turned Mr. Green’s story of confronting racial prejudice on his way to becoming the first African American to graduate from Central into something enflaming, invigorating, but ultimately feel-good. While searching for identities to live through as a teen, their struggle too easily became my own, a pose of injury I struck while seeking language for my own confusion over race and class in Little Rock. Their pain became my own, a container for all the angst I felt living in their wake.

Which had been all around me growing up. The pageantry and national attention at the fortieth anniversary in 1997, with President Bill Clinton opening Central’s doors for the members of the Nine, convinced me I’d seen the absolute zenith of commemorations. That year, my older sister, a diminutive five-foot-one, in an ankle-length brown skirt, orange padded blazer, and a short bob, introduced the president. In remembering meeting the Nine, she said recently, “It was like meeting an uncle, or someone from church. They seemed paternal, or maternal, because they understood experiences that I was having, but that I had no context or language for.”

Then the fiftieth anniversary came along in 2007, and Clinton returned, perhaps more sage and homespun and winning than while he’d been in office, reuniting with the Nine, who appeared even more venerable as I watched the proceedings on television from my apartment in Brooklyn. This year, the sixtieth anniversary will be the first without the complete cast, as Jefferson Thomas passed away in 2010.

By 1999, when I began at Central as a sophomore, the school’s black student population had reached 57 percent, though in my household, Central had long been rumored to disregard its black students, isolate them within a white student population that overwhelmed its advanced courses. Even so, I held that a distinct lineage of black achievement had begun with the Nine and traveled down through successive classes that matriculated at the school. Those “exceptions,” still stubborn to prove the capability of black students in classrooms where they seemed reluctantly invited guests, were the real legacy of the Nine. Years before I attended Central, I had begun taking note of the black students who made the “Hall of Fame” in the yearbooks my older siblings brought home, those who achieved something noteworthy in Athletics, Fine Arts, Service, or, more rare, Academics.

Meanwhile, I saw at Central among my white classmates a nexus of associations heretofore unseen by my family, webs of connections formed in parks and churches and youth groups, elementary and middle schools far west of where we lived, ones that I’d never even heard of. A practiced social climber, I envied them these connections. All of this was heady for me, thrilling more than daunting, a reason to put my head down. But it terrified me also, the idea of whiteness in my mind, a monolith that mocked the dreams I’d begun making for myself. In the face of that fear, it became useful to cast myself as black, and therefore embattled, freighted by a mission to achieve something for myself and the race, endowed by history with that chip on my shoulder, exceptional in that way. I’m not sure if anyone else saw it like that. It must also have made me insufferable to classmates, both black and white, who had maybe not read the same texts or heard the same anecdotes enough to fear whiteness or see it as the enemy of black achievement, or who hadn’t cared as much as I had at the time. Did someone ever mutter the words “haughty” or “saditty” in my wake, I didn’t catch it. The friendliness I exuded to cloak these ambitions made for good practice at politicking.

The impulse to frame my achievement as black exceptionalism sprang from a variety of sources: the wariness I’d inherited of the identities I inhabited—black and male, which I’d come to believe made me endangered; the envy I felt toward my white classmates, so oblivious to their identity and the right it bestowed upon them to want something from life. But my need to see myself as exceptional also sprang from the integration narratives I’d taken up as my own by then, I think, because I carried the impression that the only black people granted selfhood, visibility, were those who were enumerable, singled out, like the Nine. The black, bookish identity I fashioned proved useful, spurring me to study into the night, propelling me forward, even when it felt tedious, cumbersome. But it isolated me also, appeared highfalutin or standoffish enough to seem ignoble even to me sometimes, and it left me unable to connect fully with most of my classmates, the hollow gestures of a politician, my most ready response, seeming somehow counterfeit.

Still, I girded myself with a sort of righteous racial identity whenever I felt small in the face of my classmates or the dreams I hoped to pursue. The idea of struggle I drew from my burgeoning racial identity became a mission, a reason to want to achieve. My need for such a mission indicated another lack I felt, visible evidence of a black middle class in Little Rock, an antecedent for the kind of mobility I wanted to claim for myself once I entered the world. It had long felt like there was something lacking in my hometown that I imagined in the “chocolate cities” to the north and east and west, places to which black people had decamped during the Great Migration. Ethnic segregation in Northern cities had made the prosperity of black businesses possible, ensuring the survival of a black community.

Meanwhile, in Little Rock, urban renewal projects, supported by the federal government, had uprooted and displaced the black community. “In cities across America,” Alana Semuels writes in the Atlantic about places like Little Rock, “especially those that didn’t want to—or couldn’t—spend their own money for so-called urban renewal, the idea began to take hold. They could have their highways and they could get rid of their slums.” For Little Rock, neighborhood resettlement coupled with the construction of I-630, a highway that cuts through downtown to the western (whiter) precincts of the city, seemed to strip my hometown of any chance of concentrated black prosperity—enough prosperity to envy, at least, and so to strive for. Prosperous black spaces beyond the home had not really existed for me.

But black life in Little Rock had not always been so, as a recent documentary from the Arkansas Educational Television Network, Dream Land: Little Rock’s West 9th Street, reveals. The film explores the history of my hometown’s black business district, which was largely demolished to accommodate the highway that bisects the city, a history that had been completely lost to me. Released this year, the documentary revived this segregated black space, a fantasyscape to me, from the rubble. It further detailed how federal efforts to integrate, when met with stubborn cunning from some Little Rockians of that day, aroused a creativity devastatingly effective at destroying the community that might’ve been my birthright, something bright and black and distinguished as any Black Mecca I could imagine. The Little Rock urban renewal program, or what Baldwin once called “Negro removal,” a response by city planners to fears about impending integration, deliberately bifurcated the city and created the racially polarized landscape I’d grown up in. By displacing members of the city’s native black community, moving them away from the business district around which they’d milled since Reconstruction, segregationists managed to sabotage the foundation of that place.

Still, enough photos survive, enough to conjure the glamour of those lives. Enough to lead me to imagine what might have been, had those businesses survived, symbols of collective striving and cooperative economics. What credit might they have granted entrepreneurs who followed? How might those businesses have been nourished by more-equitable loan practices? The documentary presents images of black people gleeful while inhabiting black space, making purchases from black merchants. As I marveled at the glow contained in those stills, I began reconsidering what integration had meant to those communities. Had it been the moral and physical salvation of black Southern people, as I’d learned on placards in museums from Atlanta to Birmingham to Memphis? Or were those stories somehow constructions meant to disguise the erasure of a group by singling out the ascension of a few, a measly prize in the face of much larger misfortune?

It felt both delightful and peculiar to find Minnijean Brown-Trickey, a member of the Little Rock Nine, among the documentary’s commentators. “Jim Crow South?” Brown-Trickey asks herself, then continues, “Wow. Heartbreaking. Demoralizing. Destructive. And sometimes you have to have your heart broken to be mad enough to say, ‘You broke my heart. But you haven’t broken me.’” All the usual sagacity is still present in her voice. The audience up until this point has been awaiting the Nine’s story to insert itself, a compulsory part of discussions of Little Rock during this period. And yet somehow its appearance, a symbol of integration’s victory in Little Rock, trespasses here, in a film that catalogs what was lost in the name of “progress.”

Carlotta Walls LaNier also exhumes the world of the segregated Little Rock of her childhood in her 2009 memoir A Mighty Long Way, and, reading it, I was struck by the tenderness with which she treated the demarcated streets and fields and communal structures, an elegiac tone similar to that of the documentary. So many of the people who lived through the Jim Crow era in Little Rock grow wistful remembering its black community. The book illustrates how much of Walls’s famous resolve—evidenced in her bare, muscled arms beneath books and binders, jaw tensed and eyes straight ahead, the timeless power shorn into her masculine, parted haircut in those photos from ’57—had been shaped by a close-knit environment, including the abandoned lot where she and other kids (some white) gathered to play ball. Also, there’s a naiveté, a sort of dramatic irony that the reader encounters as Walls and her compatriots begin innocently submitting their names for consideration to integrate Central High. She does not anticipate how effective their effort will be, and that the cost for that effectiveness will be the loss of businesses she so fondly remembers, her grandfather’s pool hall for instance, throughout the first third of her book.

I’ve longed for spaces like that my entire life. What I saw in Dream Land and read of in LaNier’s memoir recalled the movie Polly to me, more Disney fare from my childhood. In Polly, Keisha Knight Pulliam stars as an orphaned girl who moves into a segregated Alabama town, drab but kept spotless by the sheer will of her aunt Polly, played by Phylicia Rashad. What Polly radically illustrates is an imperiled black, segregated, Southern community that nonetheless takes pride in itself, its traditions, the condition of its sidewalks. Polly is one of the few integration narratives that depicts socioeconomic diversity in segregated black America, making altruists and powermongers of black people, a stroke that humanizes the entire population. These stories dispute characterizations of those communities as tableaus of grief, peopled solely by black folks desperate to access “Whites Only” amenities, depictions that fail those people by flattening them. Polly goes even further by demonstrating the ways in which cross-cultural exchange and fellowship become more genuine and long lasting when neither party believes itself to be, or is made to believe that it is, needy. It makes a difference that when the gospel music swells and the townsfolk convene to cross the newly refurbished bridge that once segregated the town by race, the audience knows that the black citizens are not desperate for accommodation or welcome, that they bring a bounty, too, and are motivated by goodwill. A musical-theater dream, sure, but Polly supplies a vision to counter the equally fantastic ideas propagated by some white mid-century politicians about black communities as blighted areas in need of redemption. Those characterizations reek of the want to cast interventions as heroically noble, a means of evading the guilt of historic injustices that produced the blight in the first place.

For me, Polly challenged the myth that segregated black America had been bleak, and the undermining of that myth led to the weakening of another, more personal myth: the one of my being exceptional. My need to consider myself exceptional grew, I believe, from a memory not sufficiently long enough to understand myself—my ambition and its satisfaction—as a part of, rather than distinct from, a much longer tradition. Of course, an existence solely inside the American meritocracy would never demand I justify such bald ambition. But existing inside the collectivist embrace of black America did. In the late 1990s, my local cultural memory extended only so far back as the Nine and other integration efforts like the one they’d led. By believing myself a part of some uniquely ennobled tradition, I too did the work of erasing those communities, their footraces and penny candy, the gossip and goodwill that spilled across their porches.

There are two stories my mother tells when she wants to make a point about dressing for the cold. Both stories are from the period in which she faced the bitterest cold she’d ever encountered, the year she left the comforts of her segregated high school in Texarkana, Arkansas. A salutatorian of the all-black 1968 graduating class of Booker T. Washington High School that is no more, she received an affirmative-action scholarship to attend Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and fulfill someone else’s integration project. The first story is of my grandfather, a famous romantic who loved alcohol enough to sometimes burden his kids with the task of collecting him from a local watering hole where he’d passed out. Such a man, dark skinned and big eyed and long lashed—pretty like my mama was pretty, who in her school pictures recalls a young Diana Ross, only more chocolate, and with more neck—spent two weeks’ wages on a fur coat he sent my mother, who’d been calling home complaining about the Midwestern winter. The second story is of a time that same winter when she’d gone to the student infirmary and wound up in danger of having two toes amputated due to frostbite. She intends these as object lessons about the cold, but to me they also convey something about failed good intentions—of the school, which had not adequately prepared her for the weather or the loneliness or the racism she was confronting that winter, and of her father, whose extravagant gift offered poor cover for an Iowa winter.

History becomes like that cold to me in its indifference to the warmth of fully lived lives, the folks who peopled the stories it tells. Even more, the wombs in which those people were nourished seem especially in danger of being misremembered.

And so, though “separate but equal” still makes no sense, it’s important to insist that the portrait that survives of “separate” is an accurate one. The faces of black folks in pre-1960s photos seem sometimes quiet and sometimes exuberant, neither expression of which can I make my contemporary face to show. That’s easy, and nostalgic, and incredibly dangerous to say, given the reality of the alt-right today. But, to say that integration narratives disserved me is not to advocate for a return to segregation. I hear stories of black Northerners repopulating the South, of the flight of young black professionals from Northern cities today, and I imagine they long for space for black ownership, black entrepreneurship, black artistry, space they’re often priced out of on the coasts, without the benefit of the legacy wealth acquired by the grandparents of their white peers.

To my mind now, integration narratives erase native communities by design. It’s necessary to think separate and unequal also meant shabby or lacking. The more lack, the greater the achievement, the greater the moral self-congratulation for achieving integrated space. Also, the easier it becomes to forget how recently black people were denied equal access to housing and loans, and to forget the systematic removal, and eventual estrangement, of the communities those people managed to make anyway. The trajectory of that narrative may benefit a few “exceptional” black people. It does not, however, create the space for exceptional acts to become the norm. A narrative constructed as such troubles me for what effect it might imprint on generations of black people, what hazards it might mean for their ability to regard one another tenderly. One winces at the pressure the historical narrative exerts, the compliance it demands, that everyone play nice and cooperate with the shape of stories regarding integration out of a sense of mission, that saying otherwise would be enacting a betrayal against the efforts of civil rights activists. But while surveying the recent literature by and about the Nine, I found myself in conversation with them, putting forth this lament, one I shudder to say even now, given what they faced then, but that nags at my mouth, wanting to be said aloud: What exactly did your sacrifice leave us? What did it cost?

David Margolick explores just such a pressure in his book Elizabeth and Hazel by introducing an uncomfortable idea: that integration stories become parables of reconciliation, that we want them to be those parables so desperately they sometimes warp the humanity of the people involved. You’re never allowed, as the beneficiary of the integration project, to express fatigue. Or to say that the sight of a white body is still somehow strange to you. Or to say that you don’t still presuppose that your interactions with white people won’t demand a hell of a lot of exposition. You don’t get to say much at all really, or so you imagine, if the audience is integrated. Any response other than triumphalism becomes futile.

The erasure of pre-integration black community also means the loss of artifacts of black joy. Those artifacts, mementos of those places, seem harder to find today, scrubbed from memory, or crowded out by the drama of police dogs and fire hoses. Whenever I catch the stories of early classes from Little Rock’s black high schools—Dunbar, or Horace Mann—the joy such stories bring to the faces of their alums feels out of time with the Little Rock I imagine preceding 1957. Integration narratives seem complicit in the erasure of black spaces because all that remains is the suffering followed by the feel-good tone that arrives to soothe everything. So little of the glamour, and good times had by black folks, amongst themselves, survives. The hashtags hoping to conjure #BlackGirlMagic and #BlackBoyJoy reach through digital space for something no longer in the real world. A review of history more careful to exclude the fragility of its audience’s feelings might reveal more acutely painful points in the past but also might restore shades of that past that are vital.

Perhaps the boon of attending a high school like Central is that one develops a keener insight into the process by which certain events are identified as historical and other events are stitched to those as significant factors of causation, and how this becomes a process of narrativization or story shaping. Watching another decade accrue to the events of 1957 at Central offers a unique vantage from which to view the shaping, the made-ness, of history. Or not. It’s also just a school, a place made mundane through inhabiting it so frequently. Though even that nonchalance contributes to the effect I hear so many Central alumni attempt to describe: such a precious thing as that building, its façade photographed so often it appears vain, left vulnerable for casual handling by grubby, teenaged hands.

The irreverent attitude a teen is helpless against affecting still colors much of my perspective of history, black history in particular. Understanding the made-ness of these legends, recognizing the intention that informs them, makes them all begin to appear less sacrosanct.

As a teenager, having aired my intention of becoming a writer, I received a gift from an attorney friend of my father’s—a book entitled Progress of a Race, pulled from his own collection of books. He included this inscription, “Fred, Just a little more ‘light.’ You know what to do. The ancestors are with you.” In the time since I received Progress as a gift, I may have cracked its spine twice. Still, I’ve carried it faithfully from one apartment to another. Its totemic value supersedes that which it carries as an actual text. But opening it again recently, I discovered that my shock at the book’s intentions remained. Originally published in 1897 and written by Henry F. Kletzing and William H. Crogman, Progress of a Race quickly makes plain in its language the urgency of the need to speak in protest of pseudo-scientific ideas about the abilities of black people, the “attempts . . . made in the past to prove that the Negro is not a human being.” The “Introduction to the New Edition,” which was published in 1920 (it is notable, perhaps, that in the interim American black soldiers had fought bravely in World War I), Robert Russa Moton states that “No race in such a limited period and under such trying circumstances has ever made more progress than has been made by the Negro in the United States of America.” The historic necessity of books that catalogued Negro achievement says something bitter to me about the constraint that diminished expectations imposed on early twentieth-century African Americans. But the tone of these tales, along with stories of black prodigies (e.g., Philippa Schuyler, Abbie Mitchell), also carries an air of optimism, of cultural cheerleading—the accumulation of achievements, from those of the Negro soldier to the “Club Work Among Negro Women” to the “Progress in Industries” and “Educational Improvement,” all meticulously documented and capped finally by an impressively broad-reaching “Who’s Who in the Negro Race”—that convinces a contemporary reader that the aim of the narratives, however naïve or patronizing, was a genuine belief that the achievement of one somehow proved the capability of the rest.

Distinguishing such histories as these Negro achievement narratives from integration narratives is essential, I believe, because rather than working to inspire audiences, the latter isolate exemplary black achievement in the face of struggle to assure white audiences of societal progress, or even further, a phantom aim—convincing Americans that their nation has evolved on the subject of race, that it has improved, and perhaps most importantly, that there’s a collective rush toward forgiveness.

And yet, contemporary black film and the explosion of black portraiture in visual art both seem to indicate a still-present desire among black people to see themselves free of the justifications of those Negro achievement narratives and the mollifying kumbayas of integration narratives. They instead seem to want to say something about a desire to communicate one’s self as quiet, moody perhaps, but certainly self-possessed.

In a recent profile for the New Yorker, Zadie Smith’s description of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s portraits—“many handsome black men and women in unremarkable domestic settings”—felt especially sumptuous, especially lush, for that last part, the “unremarkable,” the “domestic settings.” I wonder if black people are ever spared the chance to regard themselves in such unremarkable spaces anymore, whether they find any delight therein, however small, however private. I wonder if my presence always requires a big announcement, even if I require that of myself. I wonder if I’ve only taken a need for my presence to be an occasion for fanfare from the legacy of the Nine, and if I may ever not need such a thing. Smith goes on to argue, “Yiadom-Boakye is doing more than exploring the supposedly uncharted territory of black selfhood, or making—in that hackneyed phrase—the invisible visible. (Black selfhood has always existed and is not invisible to black people.)” To this, my mind immediately rears, because I’m still unresolved on whether that’s the thing integration stole—the visibility of black selfhood to black people themselves. Nevertheless, her language gives an ambition to the restlessness I felt throughout my time in Little Rock, a pursuit that had me always wondering what kind of selfhood I could have there.

After I graduated from Central, I set out from Little Rock still in search of that self, I think, seeking higher education at Howard, an institution still defined by a kind of de facto segregation, then fleeing to a largely Dominican neighborhood to get my footing in New York, getting crazy for a while in a Williamsburg that sounds a lot like the Village of Baldwin and Anatole Broyard, then sequestering myself along the route of the famed A train to go from largely black Bed-Stuy to largely black Harlem. My life post–Little Rock could have served my grandfather just as well, during his twenties a century ago. I’m still renting here though, still in a kind of transit, still out here looking for a self to claim as my own.

I’m much too nostalgic for my moment at Central, my time in integrated space, than seems healthy. Maybe it’s nostalgia for a time before I experienced disappointment, when most everything was ambition, nothing yet attempted, missed, or achieved. I also wonder if the legacy of the dream of integration in my own life begat an overdependence on situating myself as oppositional, in a place where I don’t have a self yet, where I have to frown my way into seeing myself and being seen by others.

Having escaped the integrated space I’d already begun to eschew by the time I graduated from Central, I discovered how dependent on the experience I’d become, possessing so few faculties to disappear within a segregated community, to simply be a part.

When I happen upon reminders of my time at a historically black university, Howard, I’m forced to confront the fact that there are networks of black people, enjoying and socializing with one another, that I willfully avoided. Maybe I wanted to retain an artist’s distance, or more probably, maybe the gay self I was harboring remained too sensitive to share. I struggled constantly with the question of why I couldn’t just “be” there, why I felt the need to isolate, the same instinct that I had grown comfortable with as an exceptional black student at Central, still wanting to be feted rather than dig in and help build. It was as if being “a part” wasn’t enough for me.

And that does not account for the selfishness of the pose, how it does not consider whether there is any value in such an individualistic identity beyond me or what the cost is of this indulgence, the white idealists who lose their dream, the black folks who lose an ally.

There were times I thought myself exceptional, or told myself I was, or needed to think I was, in order to justify my pursuit of any achievements. Attaching myself to the legacy of the Little Rock Nine helped me distinguish myself, but it also alienated some part of me from classmates, my community, the hometown I could embrace only once I’d abandoned it. To discover the problem in needing to understand myself this way, I had to broaden my search beyond the integration narratives I’d heard all my life, beyond the literature of the Nine.

Most of Jack Butler’s 1993 novel Living in Little Rock with Miss Little Rock concerns the marriage of its protagonist, the wealthy lawyer Charles Morrison, and his beauty-queen wife, Lianne. The wrath these liberal darlings eventually stir up in this fictional version of my hometown doesn’t entirely eclipse the tragedy of an ambitious black lawyer, Lafayette Thompson, who works alongside Morrison at the law firm.

Having gained access to the world depicted in the society pages of any midsize Southern city, first by drawing acclaim as a fearsome member of the state’s major college football team, the Razorbacks, then by civilizing himself into a lawyer successful enough that the firm considers naming him a partner, Lafayette wrestles with the same apprehensions concerning white privilege I confronted as a high school student. Considering the appearance of wealth and advantage his boss Charles Morrison evinces, he thinks to himself:

How conscious was it? Lafayette wondered. How much thought did the man give it? Because if he gave it a lot of thought, well, then he was mortal, he was on Lafayette’s level, with just a lot more bucks. But if—and this was what Lafayette was afraid of—if he simply did it, simply assumed this easy appearance of confident fabric and masterful stitching, why, then he was, like the dude be saying, awesome. Terrifying, a phenomenon, the door slammed in old laughing boy’s face, the final proof that there was for sure and always a world some people could never enter, a heaven you couldn’t buy no ticket to.

This fear drives Lafayette, just as it drove me, to pursue exceptionalism so singularly. He does not recognize the resentment his interracial relationship arouses in the Little Rock of the late twentieth century, and he lands in jail when he’s rounded up by police raiding a party that’s spiraled out of control. The misdemeanor indecent-exposure charge costs Lafayette the prestige and accommodation he’s grown accustomed to, a loss so devastating, he’s forced to return to the small black community he thought he’d left behind.

He actually went to church, his daddy’s old church, way out in the country, and he didn’t feel superior to the whiskery feeble old gents and stooped old ladies who mostly populated it. He just listened and watched, trying to learn what he could. After all, they had gotten nearly all the way through their lives without making a god-awful mess of things.

Lafayette spends the novel in search of an authentic self, returning home to inspect a community he’d only ever looked beyond, enticed by a contentment and dignity there that he’d once viewed as threadbare.

Later in the novel, while performing court-ordered community service, Lafayette reveals his backstory to a surly inmate he’s been assigned to counsel, and his frustration expresses the same fear that led me to regard myself as exceptional in Little Rock:

I thought I fixed myself. I figured it out, I was big-time, I beat the game. And the next thing I know, I’m all broiled up in somebody else’s story. . . . I didn’t watch myself, so here I am. I don’t get to say what my own story is. Just like in college, I have to play whatever position they tell me to.

CHARLEY

CHARLEY

Charley and Lafayette both hold themselves apart from their communities, erecting scaffolds of their achievements, then ascending them to reassure themselves. Both characters confront tremendous, longstanding fears about their worth upon their returns, a lesson to me about what holding oneself up as exceptional often means in the first place. The voices that confronted both those characters, sometimes merciless—hurt from the insult of having been judged worth leaving—sometimes consoling, recalled my father’s voice over my want to grow dreadlocks. It wasn’t the hair, I believe, but the need to hold myself apart that he wanted to soothe in me.

Last January, once I’d successfully managed ten years in New York, the thought of returning home began asserting itself to me. I’d faithfully visited Little Rock two or three times a year in the time I’d spent away, and found myself much more comfortable there now, in my adult body. I’d grown older in my blackness and maleness, making those things less precarious to me. And although returning would mean lugging back other identities I’d since taken on, accepting the potential erasures and microaggressions, the fear I might feel sharing that self with my community, wanting accommodation for it now, I could begin to imagine myself as capable of that feat, too, being closer to selfhood, possessed of identities I’d rightfully earned.