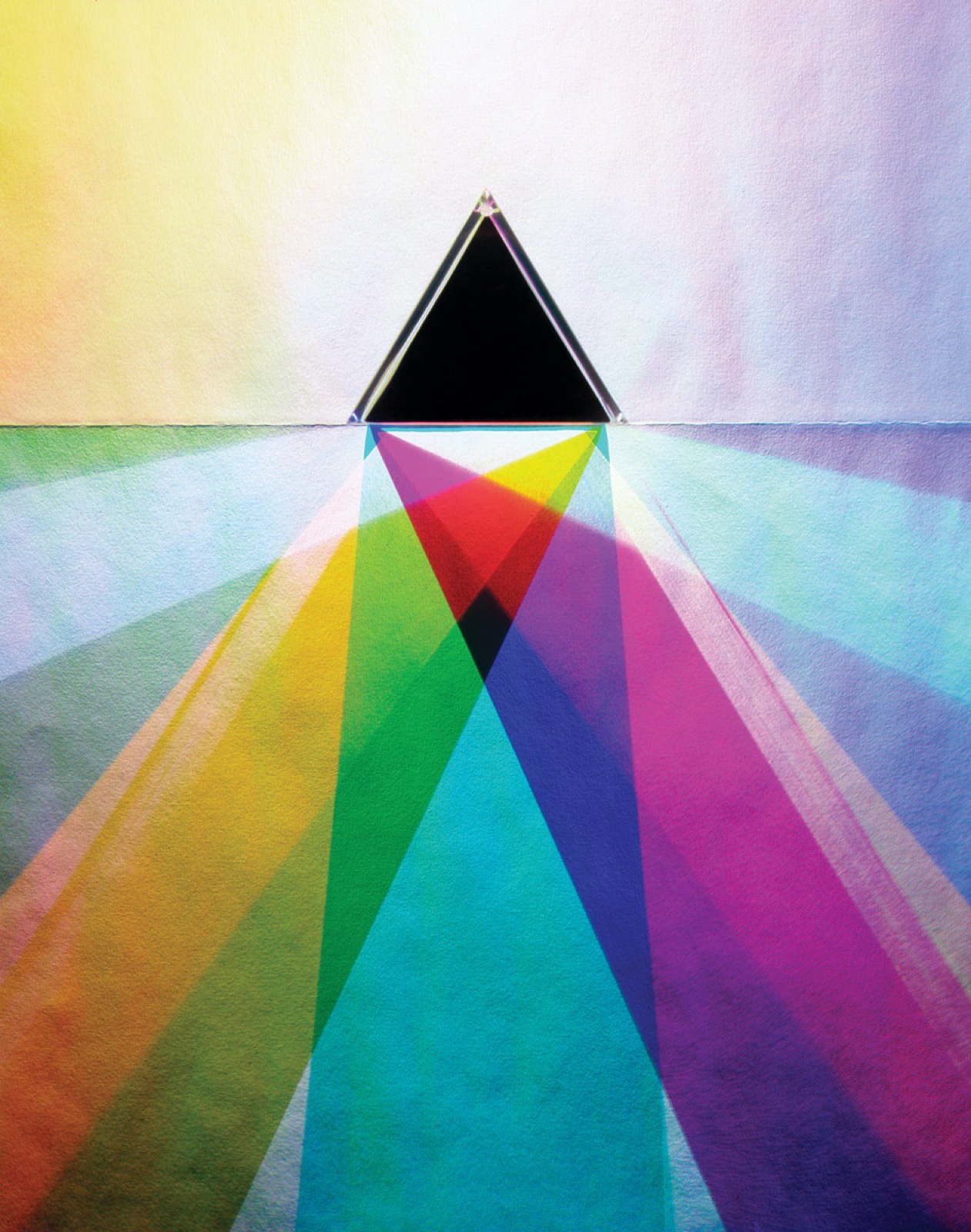

“A Variety of Colors Created with the Shadows of a Prism #3” (2019), by Caleb Charland. Color separation with three black-and-white paper negatives

Look for Shape, Look for Shine

By Liam Baranauskas

T

he teenage waitress at a Waffle House in Hot Springs, Arkansas, tells a customer sitting next to me at the counter that she’s scared of the dark. He’s incredulous. “What’s in the dark you’re afraid of?” he asks.

“I don’t know!” she says.

I think this is a wonderful answer.

“I lived in a haunted house,” she explains. “Before.” She tells him about a photograph her grandmother took. “There’s a little girl. Standing behind my cousin, by the microwave. A little girl with a bow in her hair.”

“See, what I think is you believe in that stuff and then you start to see it.” The man is thin, probably in his seventies, and punctuates each sentence with a toothy grin. He turns to me, clearly eavesdropping. Big smile. “Right?”

The waitress seems exasperated. Why should she doubt what she’s confirmed with her own eyes?

Hot Springs sits in a valley surrounded by Arkansas’s Ouachita Mountains, which produce larger and more numerous specimens of high-quality, water-clear rock quartz crystal than anywhere else in the country, maybe the world. Supposedly, somewhere in these mountains is the crystal vortex. That’s what I’ve come to find, even though I’m not sure what it is, or even if it exists.

Years ago, a friend told me about a trip she had taken to upstate New York (where the quartz comes in large-faceted crystals known as “Herkimer Diamonds”) during which she meditated at a spot known locally as a vortex. It made her pass out. She was unconscious, she says, for hours.

I don’t remember how I heard that Arkansas was a hot spot for vortices, but I remember researching them a few years ago at a Hot Springs hotel. On websites full of jargon, digressions, and often incongruous technological analogies (“It is akin to your television changing from the archaic antennae to satellite reception”), I learned of Atlantis, Lemuria, the Atla-Ra (who vibrated at the level of twelfth-dimensional light and energy), the Sirian-Pleiadian Alliance, and master crystals in the Ouachita Mountains linked in intra-space within a frequency of parallel hyper-dimensionality. Or something. Much of the prose was studded with rhetorical flourishes like “You see!” and “I tell you!” punctuating particularly incomprehensible points. I learned that the vortex was upswelling, and that the new era was upon us. But I never found anything telling me how to find the vortex itself.

I ended up wandering around Hot Springs National Park. The quest was half-ironic, but I was hoping at the same time to feel something I couldn’t make fun of. If a revelation from the Earth manifested inside my body, well, that would mean some of that light was in me, too.

I meditated on a big rock. Nothing happened. I hiked to the gift shop at the observation tower and bought a t-shirt.

You believe in that stuff and then you start to see it. What if that’s not an admonition but an instruction? Leave it to the skeptics and scientists to follow chains of proof to a conclusion, and instead take the path of the churchgoers, the ghost hunters, the conspiracy theorists, and the visionaries who start at the end and trace the bread crumbs back.

“If I had my phone I could show it to you,” the waitress insists to my countermate. “A picture of my cousin. And this spirit. Right by the microwave.” She repeats the detail about the microwave as if it will make the ghost as ordinary as an old lady’s appliances.

The man shakes his head. He’s talking to me and the waitress both but maybe mostly to himself—his speech quickens, a syrupy accent strange enough to my ears that I don’t quite catch everything he’s saying. The gist, I think, is that he’s had his problems with women, and his nephews run in gangs. He was in the military, did a tour in Vietnam. He laughs.

“I’ve seen too many dead people to be scared of ghosts,” he says.

Andrew McCormick is a geologist for the National Forest Service who, among other tasks, is in charge of evaluating potential mining claims on land in the Ouachita National Forest. There are twenty different entities—companies or individuals—that legally mine quartz here. Everyone knows Andy. Even if the Forest Service itself is slow, intractable, and bureaucratic, no one has a bad thing to say about him. I haven’t told him I’m looking for the vortex. He’s a scientist. I’m afraid he’ll think I’m an idiot.

One of McCormick’s errands today is to deliver paperwork to James Zigras, who runs Avant Mining. The larger mining operations in the Ouachitas have two distinct potential revenue streams: the claims the owners hope will yield untapped veins full of large, clear rock quartz to be sold wholesale to dealers and serious collectors, and the public-facing areas that sell pre-cleaned crystals and gems (many of which come from other parts of the world) and allow rockhounds to dig their own quartz from tailings in which the most lucrative veins have already been discovered and excavated. Ron Coleman Mining has RV camping sites and zip lines. The smaller crystal shops along the road through Mount Ida, the “Quartz Crystal Capital of the World” some thirty miles west of Hot Springs, advertise crystal healing or reiki or readings. One also rents tuxedos. “There’s not a lot of job opportunities here,” McCormick says of Garland County. “Rockhounding is the big draw.”

Avant Mining does not rent tuxedos. They sell crystals to high-end jewelry company David Yurman. Specimens from Avant mines are exhibited at the natural history museums in London, Washington, D.C., and New York. Avant is headquartered in two metal-sided warehouses separated from the road by a chain-link fence. There’s no sign. Zigras is long and thin and moves with the confident lethargy of a touring musician wandering a Love’s truck stop between gigs. Later, at the mention of his name, someone I’m talking to will dismissively mutter, “Oh, the millionaire.”

McCormick tells him, “Merry Christmas,” when he hands Zigras a manila envelope. Zigras says he’s promised a huge crystal from this claim to the Smithsonian.

“You’ve already gotten it out?” I ask.

“I know where it is,” he says, grinning.

When crystals are brought in from one of Zigras’s mines, they initially pass through the first trailer-size building to be rinsed off on long, mesh-covered tables before being plunged into a dumpster-size vat of muriatic acid. The cleaned crystals are then sorted and stored in the bigger building, which seems vast from the inside, though it might be only the size of a large revival tent. Part of this illusion is the overwhelming amount of quartz in view. Rows of squat, open-topped cardboard filing boxes are stacked on tables and each other, each filled with crystals. Most of the stones themselves are as clear as window glass, so what’s visible is as much the light passing through the quartz as the quartz itself. There’s a gravitational effect to this. It’s as if the air around us is being pulled through the crystals, shrinking and expanding simultaneously as it refracts, and everything in the warehouse that’s solid—the walls, the tables, the boxes, ourselves—becomes, in contrast, a banal husk made of something less important and beautiful than light.

There’s an endless variety of quartz formations in the boxes. Some crystals come in long icicles, some look like the translucent fruit of an invisible tree, some like barren, glassine shrubs, others like sun-bleached coral. Some of the crystals too big to fit in boxes are left attached to a sedimentary stone bed—called a matrix—that, millions of years ago, guided their growth. These huge formations are clustered with transparent stalagmites, throwing sharp-angled blooms toward the fluorescent bulbs overhead, a hint of the Lovecraftian to their mix of order and chaos.

In 2014, Zigras excavated a five-foot-tall, fifteen-hundred-pound quartz crystal he dubbed “The Holy Grail,” which is currently held at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, opened by Alice Walton, an heir to the Walmart fortune. Walton is a known metaphysical enthusiast—among other things, she spoke alongside Deepak Chopra at a 2019 symposium held at Crystal Bridges that sought “to explore the future of well-being and reveal the impact of integrative health, humanity and the cosmos.” The Holy Grail went to Bentonville as part of an exhibition called Crystals in Art: Ancient to Today, for which Avant supplied much of the raw and archaeological crystals. The rumor is that Walton bought the Holy Grail from Zigras, but he’s publicly declined to comment on whom he sold it to or for how much, except to call it “the most expensive and valuable Arkansas quartz ever sold,” which would indeed put its value well into the millions.

Zigras is nothing if not proud of his treasures. He takes me into a shipping container that houses what’s been returned from the Crystal Bridges exhibition. He shows me a quartz asp carved in Egypt thousands of years ago and a smoky crystal pendant surrounded by knotted metalwork that once hung around a Viking’s neck. He shows me a “phantom,” a stone in which the quartz encases another black crystal made of manganese, which looks as if the crystal contains its own shadow. He shows me how the internal refractions of another crystal create a hidden rainbow inside it. He says the metaphysical people go crazy for rainbows.

Then he leads me into a small room tucked into a corner of the warehouse. This one is completely empty save for a single, enormous clustered crystal mounted on a custom-built pedestal. The effect of its isolation is disconcerting, like this crystal has to be quarantined from the others. It’s about four feet long, with hundreds of sharply defined points the size of wine bottles rising from its quartzite matrix. He flicks a switch and LED lights illuminate it from below. The crystal evokes movement even as it stays perfectly still, its translucent towers twisting and striating, like a snapshot of an alien city’s skyline being wracked by an earthquake. Zigras has named it “The Bouquet.” He tells me he took it to Art Basel. It’s on his Instagram. It came, as did the Holy Grail, from a mine he calls “The Vortex.”

“A Variety of Colors Created with the Shadows of a Prism #1” (2019), by Caleb Charland. Color separation with three black-and-white paper negatives

“A Variety of Colors Created with the Shadows of a Prism #1” (2019), by Caleb Charland. Color separation with three black-and-white paper negatives

Everyone I talk to in Arkansas who’s involved with crystals, even those who aren’t following some sort of esoteric path, has heard of the crystal vortex. It’s become a sort of underground tourist attraction, one not mentioned in guidebooks but firmly in the regional parlance. The thing that no one can answer is where, or what, it actually is. Marci Lowery, a clerk at All Things Arkansas, a shop in Hot Springs that, on the day I visit, has three huge blossoms of quartz in its window display, describes tourists double-parking their cars on busy Central Avenue to run in and ask her the way to the vortex. Lowery, who says she doesn’t know much about crystals other than that “they’re pretty,” has never had any idea what to tell them.

Traditionally, keepers of secret knowledge hide their mysteries via a tortuous web of symbol and contradiction, through which experience and intuition are one’s only map. Information finds you, not the other way around, and when it does, it’s anecdotal and based on perception, inherently untestable with the scientific method. This is both a feature and a flaw. It serves to protect the knowledge itself, but any fan of Flannery O’Connor can tell you that faith acts as a beacon, calling charlatans and confidence men.

Charlatanism, it should be said, does not preclude holiness. The trickster figure exists in some form in just about every spiritual tradition. While traveling through South America looking for ayahuasca, William S. Burroughs wrote, “The most inveterate drunk, liar and loafer in the village is invariably the medicine man.”

When I ask Zigras why he called his mine the Vortex, he explains objectively at first, telling me the vein spirals up toward the surface in a vortex shape, but then he goes off on a tangent that, though he’s been reluctant to address it so far, sets him on the edge of metaphysics. It’s a curious change. He tells me how the structure of quartz is itself a vortex, the silica atoms curling like unzipped DNA along the vertical axis of the crystal. He says that when Alice Walton opened Crystal Bridges, it “shifted the energy in the whole state.” He compares the process of seeing a crystal being excavated to witnessing a birth and says he’s seen people start crying when the crystals emerge. Finally, he asserts that he believes the crystals called him to Arkansas. “They weren’t being appreciated,” he says. “The crystals were getting pretty aggravated.”

Later in the trip, I visit Richard Wegner, who runs Wegner Crystal Mines in Mount Ida. Wegner believes the vortex is real but is hesitant to define it. “Everybody can explain it in their own way,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be any kind of description of what it is. It just is.” He rolls his eyes when I tell him that Zigras has named one of his mines the Vortex. “Probably the whole quartz belt is the vortex here. Which is hundreds of hundreds of square miles,” he says. “If someone claims, ‘This is the vortex,’ I’m like, ‘Sure it is. And you pinpointed it out?’”

Part of the vortex or no, not every claim in Garland County yields riches like Avant’s. McCormick takes me next to a cartoonishly dismal pit mine that requires about a fifteen-minute hike once we park at a locked boom gate. “They looked at prospecting research from World War II,” he tells me of the mine’s claimants. “They did their exploration. It just didn’t have what they were looking for.”

The mine’s vertical walls droop from the mountain’s slope, indecently exposing the roots of trees along its edge. Junk timber lies amid huge white chunks of ugly and opaque—and therefore worthless—bull quartz. A recent rain has turned the iron-rich red clay goopy, cementing dead leaves to the undersides of our shoes.

“Hard rock deposits are very erratic,” McCormick continues, explaining why this mine proved a dud. “It’s not like coal where the seams are straight. You might drive a tunnel thirty or forty feet and miss the vein by a foot.”

Quartz is piezoelectric, which means it produces a constant, measurable electric charge when outward pressure is applied. In World War II, Arkansas quartz’s piezoelectricity, along with its clarity, made it a valuable industrial product, used in everything from bombsights to wristwatches. Today, most quartz for optics or oscillators is synthetic, but healers and meditators want stones straight from the Earth. Some metaphysical practitioners claim they can feel piezoelectricity in their hands when they squeeze a crystal. Literally, it gives them vibes.

When crystals became retro-fashionable in the 1980s, McCormick says, there was a huge increase in both the value of quartz crystal and the number of mining applications opened in the Ouachita National Forest. “Most of them didn’t know what they were doing and left after a year or two,” he says of the newcomers to the area. “A few learned from the people who lived here, and they stayed.”

One of those people who lived here was David Lebow, a fourth-generation quartz miner who died of cancer a few years ago. McCormick reenacts both sides of a remembered conversation with him. “‘Andrew, what do you see here?’ ‘A rock, sir.’ ‘Well, see this black material on this side? Black is manganese, means it’s a good prospect to dig on this side.’”

I’ve been staring into the clay as we walk through the pit, unsuccessfully scanning for quartz. Seemingly with little thought, McCormick bends down and plucks something from the earth, brushing it off before he hands it to me.

“These guys learned going out with their dads and grandpas,” he says, shaking his head. “They might not have a third-grade education but it’s mind-boggling to see what they see on the surface.”

The crystal McCormick gave me is basically worthless, so tiny it might fall through the mesh rinse screens at the Avant warehouse. It’s also around three hundred million years old, formed while this land rose from what was then ocean shore and became mountain. You’d die trying to write the zeros you’d need to represent the length of the odds of it finding its way into my hand at this moment. Mathematically, it’s not here. Geologically, scientifically, it’s a miracle.

I squeeze it and don’t feel even the slightest spark. McCormick stoops and uncovers another one. They’re everywhere if you know what to look for.

I meet Genn John and Susan Waters at Peace Valley Sanctuary in Caddo Gap. Over email, John suggested this as a place I might be able to feel “X-marks-the-spot vortex energy.”

“I guess she’s had some big activations and stuff going on, and I can definitely feel the energy,” John tells me. “My heart’s pounding. So if I sound anxious, that’s why.”

What’s activating, supposedly, is Peace Valley’s vortex, and what’s weird is that I’m feeling the same way. It didn’t occur to me that this feeling might be caused by vortex energy, but I noticed the roiling in the pit of my stomach about half an hour before I arrived. I missed two turns. I’ve had to keep reminding myself to breathe.

Peace Valley is more than seventy sprawling acres of gentle hills, neatly landscaped and scattered with small outbuildings. A pair of Chihuahuas named Athena and Charlie Brown harass a peacock on the shore of a placid lake. Waters, Peace Valley’s owner, hosts metaphysical workshops here and rents the outbuildings on Airbnb. She’s named some of the Airbnb rentals things like Lemuria or Alcyone (a star system in the Pleiades) to honor the interdimensional beings who are brought to Peace Valley via a stargate linked with Helios, the enormous sentient “Earth-keeper” quartz crystal growing beneath her house.

Waters tells me about Helios and the stargate within a couple minutes of my arrival and then says, laughing, “Let me know if this is all getting too woo!” This, I will learn, is her all-purpose and knowing term (sometimes “woo-woo” or “the woo”) for anything that her Baptist neighbors might find beyond the pale.

I tell her no, I want the woo.

Waters’s soul has been present with Helios since before Atlantis fell; they have the same energetic blueprint so the transmission of energy between them is seamless. This puts her in a unique position with regard to the consciousness grid between crystals. “If there’s a place on the planet where the grid is broken, I go there,” she says.

Once, the Arcturians told her to go to Greece, where they took patterns off her emotional body every night for six weeks, cleaning the Atlantean crystal consciousness grid and uploading it into her energy field. She downloaded the grid into Helios on her return. (“So you were basically a flash drive?” I ask. “That’s right,” she answers.) This had a pressing purpose: in this stage of astrological precession, Waters says, humanity has begun converting itself from a fifth- to a sixth-root race, changing “an electromagnetic body to a more crystalline and more silicon-based as opposed to carbon-based.”

“Our physical bodies?” I ask.

“Our physical bodies,” Waters says. “Correct.”

Waters is saying that we will literally become crystals.

“It’s in this civilization that it’s going to happen,” she affirms. “In Arkansas.”

She says it so matter-of-factly, she might be describing some landscaping work she had done. It’s the same way she tells me about the “curriculum of consciousness” she’s written, the frequency fence the Arcturians have erected around Peace Valley, and her friend Dennis, whom she describes as “a fix-it man for the Milky Way.” This isn’t secret knowledge she’s hiding from me, but it’s still so far from anything in my realm of experience that it makes my head spin.

“Why don’t we go outside,” John tells me gently, “so you can feel the energy.”

Some of this is just as new to John as it is to me. She’s only briefly met Waters once before, when she visited Peace Valley for an event on November 11, 2011 (repeating dates often mark energetically significant times in this branch of crystal theology). John also believes crystals are sentient but she says Waters’s knowledge is more “academic” than hers. “The histories and the root things, those are things I’ve kind of heard but nothing I’d be able to spill out.”

John is the author of Understanding the Crystal People: A Handbook for Lightworkers, and she maintains a website about how to work metaphysically with quartz according to its crystallographic structure. She’s from a family of rockhounds, but one in which if you said you felt something from a rock, you were “kooky.” Then she discovered that wading in a lake that had quartz in it seemed to help alleviate the pain of her treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Pretty soon, she says, “I was out there with my chemo port and digging crystal.” As she recovered, she started getting vision-like “stories” from her crystals and, over time, “learned to channel the crystal kingdom” with the help of her spirit guides, Venus and Cassandra, who dictate a lot of the information for her website to her. She takes notes from them on her phone.

Do I need to say that both John and Waters are clearly intelligent, funny, and self-aware? John is an autodidact who taught herself HTML while wading through countless dense crystallographic texts to create her website. Waters, as an example of her ability to compress time, laughingly tells how it helped her to stop being late to pick up her daughter from the airport. And while I think what they’re saying is implausible, a lot of it also comes as firsthand stories, which makes doubt a moral choice as much as an intellectual one. When someone tells you about something that happened to them, it takes a lot of presumption to look them in the eye and say, “No, it didn’t.”

The four of us pile into a golf cart—me and Waters in the front, John and her wife, Patti, who’s been wandering the grounds, sit behind us—and we ride across the rolling hills of Peace Valley. Waters tells me about star-beings from Orion and of “Golden Healers” who have visited her here. Golden Healers resemble bees and come from a constellation called Beehive. They once saved one of Waters’s dogs when it fell from an unfinished porch on the second story. Also, a “Lady of the Lake” recently appeared to Waters for the first time. As we putter over brown January grass, a heron lifts from the lake’s shore.

About halfway up a small hill that leads to a Pleiadian portal, the golf cart begins grinding. It slows and then stops, giving off the telltale cloying smell of a shorting electrical system. We get out and push in hopes that the motor will catch, but it’s no good.

Patti, John says, is a mechanic. She used to work on helicopters. “Why don’t you guys check out that portal?” Waters says to me and John, while Patti lifts the golf cart’s seat to look at the motor. We’re to stand at the “gate” and ask permission to enter.

The portal, honestly, is pretty janky. It’s an arrangement of rocks, the line broken where you’re supposed to step through. I don’t know what I’m expecting when John and I ask humble permission and walk into the clearing beyond, but nothing really happens. “I feel kind of muffly,” John says. “Like my energy’s more kind of in . . . ” She trails off, sounding a little disappointed. After a minute or two, the Chihuahuas come running after us. “Did you see that?” John says. “They ran right between the rocks!”

I leave John in the portal and go to sit by the lake. The surface is still. Night is coming and it’s getting cold. My nerves have finally calmed. Waters might say this is because high frequencies consume low frequencies, so I’m becoming attuned to Helios’s energy. But no Arcturians, Pleiadians, beings from Orion, Golden Healers, or Ladies of the Lake appear to me. Patti’s pickup truck passes behind me, towing the golf cart, Waters riding shotgun.

Back inside the house, John asks if I saw the two blue lights in the forest while we were at the portal. “I’m going to ask her about them,” she says of Waters. “They’re probably just solar lights.”

When Waters returns, she says that what John saw were life-forms called “Blue Beings.”

John beams. “Oh, that’s so cool!” she says. She looks as happy then as anyone I’ve

ever seen.

There’s something Waters said that, weeks later, still sounds to me like, well, woo—unjustifiable, even conceding that her experiences might be true for her, if no one else.

“We are energetic in nature,” she told me. “Thoughts are electrical, feelings are magnetic. And they form an electromagnetic field, and that is how we create reality—from a thought and a feeling being attracted to each other and manifesting as an event, as a whatever.”

I tell my wife that I understand what “thoughts are electrical” means. Sure, synapses firing are literally electricity. “But what does ‘feelings are magnetic’ mean?” I say. “How are feelings magnetic?”

“It makes sense to me,” my wife says. “They are.”

“Maybe as a metaphor, okay,” I say. “But it’s weird to combine poetry with something that’s objectively, scientifically true.”

My wife looks at me. “It doesn’t sound like this woman thinks that’s weird at all.”

I realize that I don’t either.

The day I’m to leave Arkansas, I make a quick stop on my way to the airport to meet a woman who gives her name only as Becky and who, along with her husband, owns a quarry called Sweet Surrender in a town called Story. Sweet Surrender is a textbook mom-and-pop mine, with the vibe of the places Andrew McCormick described as often running afoul of Forest Service rules because they can’t afford to do things legally. A busted trackhoe sits about halfway down one of the pit’s slopes. Becky has a smoker’s voice and a habit of punctuating her sentences with a wink. She tells me, apropos of nothing, “Look for shape, look for shine.” I assume this is advice on how to spot crystals, though I never asked.

Four dedicated rockhounds chip away at the clay in the pit on this Sunday morning. One of them is excavating the dirt around one of the trackhoe’s treads. Becky’s mechanic, Carl, says he’ll get it running again soon. Carl is wearing a camouflage jacket and hat and may be anywhere from forty to seventy years old. His eyes dart with a preoccupied animal quickness, as if constantly recalculating the risk of whatever’s going on around him.

“I can work with the metaphysics or I can do the bullshit,” Becky says. “One woman says I’m very intuitive. Another says I’m very psychic. I don’t know what they’re picking up on. Sometimes things just come to mind. The picture, you know.” I nod, even though I’m not sure whether Becky’s saying she is or is not a medium.

Her gaze is discomfiting. “I’m getting that she’s a nice person,” she says. “I could be bluffing, you know what I’m saying. An R with an A. Am I right? Roberta?”

I don’t know anyone named Roberta. Or anyone whose name starts with an R and ends in A and is a nice person. It seems like she’s giving me the routine of the carnival psychic, spitting out overly general guesses that seem prescient but have some degree of truth for most people. I nod again anyway. She winks.

“People come up here and think there’s so much energy,” she says. “I don’t feel piezoelectric energy.” She turns and yells at Carl. “Carl! Do you feel energy from crystals?”

“When I’m diggin’ ’em, I do,” he says.

It turns out Carl is a rockhound, addicted, he says, to digging. When he started, he tells me, he didn’t know a thing about quartz. He was working in Hot Springs for “the biggest dickhead I ever knew in my life. He wouldn’t hire nobody who wasn’t an alcoholic too. He’d drink with us on the job. I’d drink a thirty-pack a day every day.”

Since he got in the pit, Carl might have a beer with “an old man” he knows once in a while but otherwise he doesn’t drink anymore. “I’m looking for something,” he says.

I ask Carl what he’s looking for.

He shrugs. “You never know what you’re gonna find,” he says. “You see one point—is it a cluster, is it a triple?”

Intuition is a social leveler. In stories, it’s often bestowed upon the dispossessed, the Waffle House waitresses, the fourth-generation quartz miners, the rebellious Jewish carpenters. This creates a whirl of irony. Quartz is the second-most-common mineral in the world, so its worth is almost entirely as a material representation of intuition. Places like Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges museum validate this worth institutionally, but that’s nothing without authentication by people who know. A chain of metaphysics and unwritten geologic folkways has helped keep Garland County financially afloat. The churn of market forces might not make belief real, but it can put a price tag on it.

So where does the belief—any belief—come from in the first place? My guess is desire. Desire to fill a lack in ourselves, to have what we think and feel be real, to live in a world of more than what’s before our eyes. We want there to be something in the dark, whether it’s to be loved or feared. Better either than a void.

Carl says sometimes he can tell when a crystal “just needs to be dug.”

Look for shape, look for shine. Do the metaphysics and do the bullshit too. Know the material borders of your world but don’t neglect the ethereal, the things you can’t hold in your hand. Visit interdimensional stargates in a golf cart. Let the dead people you’ve seen become ghosts, and let them go into another dimension, or wherever ghosts go when they’re not hanging out by the microwave. Feel your real pain turn diaphanous. Let light into your crystalline body.

I realize that the end was the beginning all along. You believe and then you start to see it.

As Becky tells me: “Who am I to tell you you’re wrong? I might think you’re full of shit, but what if it works?”

And now I will tell you how to find the crystal vortex:

Go to a Hot Springs Waffle House.

Sit at the counter. Order whatever you want.

Pay attention to metaphor and misinformation.

Let a thought and a feeling manifest as an event, as a whatever.

The crystal vortex does not exist and it is also everywhere.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.