The Music of North Carolina

By Oxford American

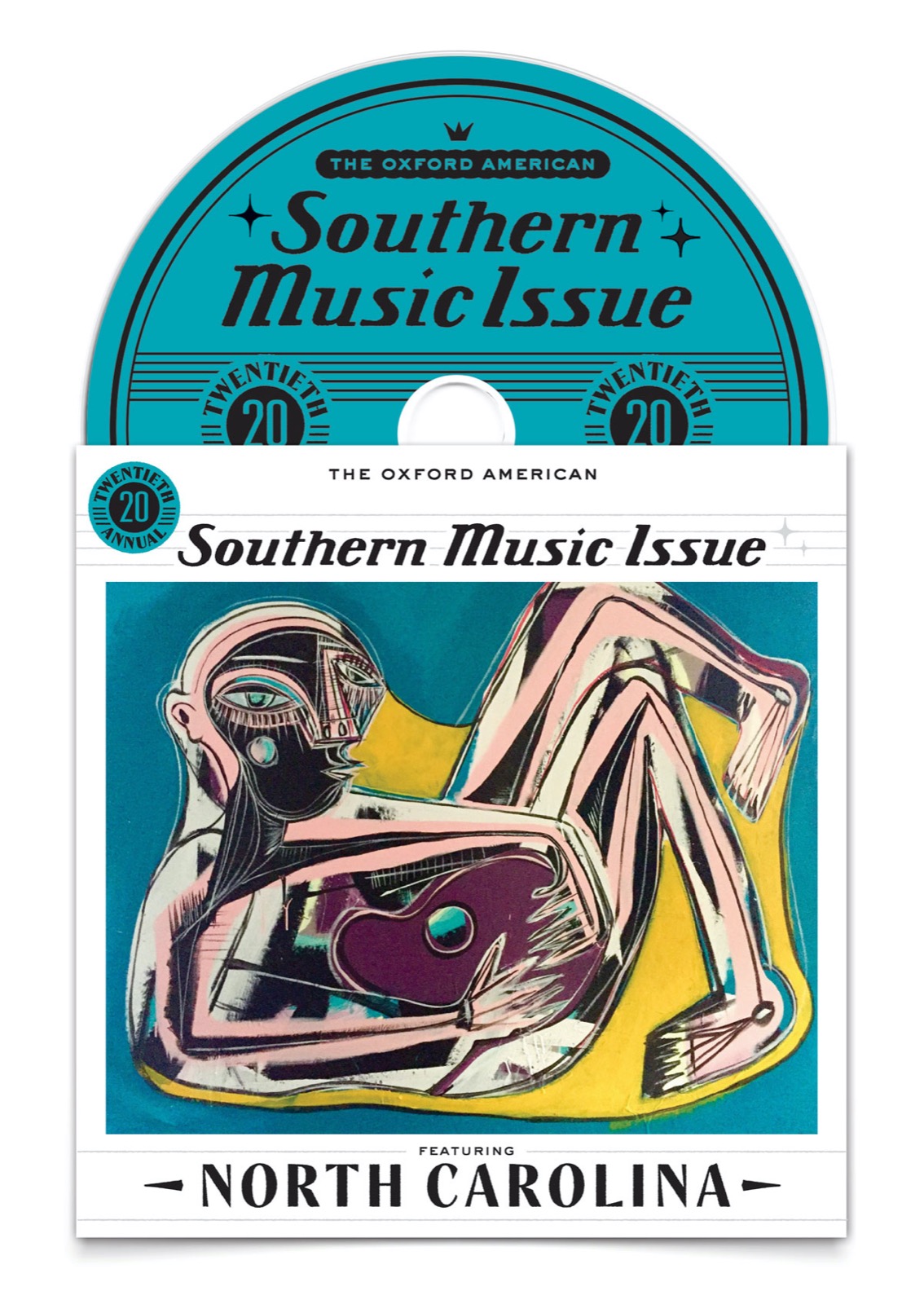

Untitled (1967) by Minnie Evans. Courtesy of Cleo F. Wilson. Photo by Cheri Eisenberg

Notes on the songs from our 20th Southern Music Issue Sampler featuring North Carolina

Order the North Carolina Music Issue & Sampler

Welcome to the twentieth installment of the Oxford American’s Southern Music series. North Carolinians are not shy about celebrating their achievements—see: FIRST IN FLIGHT; the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence and the Halifax Resolves; America’s earliest public college; Pepsi; Michael Jordan—and in the realm of music, the land of the longleaf pine has had a deep and enduring influence. I will tell you right off that a lot of the stories and songs in this issue are about pride.

The profiles, eulogies, and essays herein boast of remarkable achievements of North Carolina’s musicians across eras and genres: from unassailable legends (High Point’s John Coltrane, Tryon’s Nina Simone, Chapel Hill’s James Taylor) to contemporary masters (Snow Hill’s Rapsody, Jacksonville’s Ryan Adams, Raleigh’s 9th Wonder) to the seen-afresh (Dunn’s Link Wray, Kannapolis’s George Clinton, Winston-Salem’s dB’s, Charlotte’s Jodeci)—and, of course, the often-overlooked and in-between (Winston-Salem’s Wesley Johnson, Morganton’s Etta Baker, Chapel Hill’s Liquid Pleasure, Kinston’s Nathaniel Jones, Black Mountain’s period of hosting John Cage).

The songs on the accompanying sampler (you can listen to the CD that came with your magazine, or via digital download using the code on the card inside the disc sleeve) were made across almost one hundred years—from April 1924, when Samantha Bumgarner and Eva Davis cut “Big-Eyed Rabbit” on 78 rpm, to September 2018, when Shannon Whitworth recorded a beautiful new version of Ella May Wiggins’s 1929 protest ballad in Asheville especially for our mix. In between, you have moments of transcendent musical history: Coltrane joining fellow North Carolinian Thelonious Monk’s band for some months in 1957; Earl Scruggs and Doc Watson sharing a stage in Winston-Salem in 2002; Cas Wallin hollering an old ballad of Madison County into a field recordist’s microphone in 1963; Sylvan Esso reconfiguring its music live on all-Moog synthesizers in 2013; Big Boy Henry talking his improvisational blues in 1982; brothers Vernon, Doug, and Link Wray gathering around a tape recorder in their kitchen in 1952. Some of these songs have not been publicly released until now.

This is the seventh Oxford American Music Issue I’ve worked on, and it’s always rewarding to dig into the South’s bottomless musical bounty. It is with overwhelming pride and Tarheel allegiance that I introduce the music issue devoted to my home state. North Carolina, I love you.

In the second week of September, as we were in the last stages of polishing the stories and finalizing our track list, the brutally slow-moving Hurricane Florence made landfall in Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina, beginning its slow crawl inland, bringing thousand-year rains to the eastern part of the state and triggering devastating flooding across a huge swath of the Atlantic Coast from Virginia to South Carolina. For much of the year, we had been at work on a project devoted to the immense cultural influence of the Old North State, and suddenly we found our beloved subject, a place of such history and beauty and diversity—and the source of so much important music!—under siege.

Many Oxford American contributors and readers were affected by the storm. For a week or more, phone lines and email inboxes went dark as North Carolinians fled for higher ground and then returned home to find their lives turned over. Novelist Wiley Cash, who writes about Wiggins in our liner notes, evacuated Wilmington with his family. In Robeson County, the Lumber River surged over its banks: the same river where Lumbee historian Malinda Maynor Lowery’s mother was baptized, as Lowery describes in her essay “The Low Hum.” Novelist Jill McCorkle is from there, too, and the places that inspired her nostalgic essay about beach music, that Carolina coast phenomenon, were among the hardest hit. Also in the storm’s path was Beaufort, hometown of bluesman Big Boy Henry, whom Tom Rankin profiles; and Maceo Parker’s Kinston, the small city that lays an outsize claim on the development of funk, as Sarah Bryan chronicles in “Really Is Hard to Beat.” In the aftermath, Ryan Adams, whom I pay tribute to in "I Would Call Myself a Gardener," shared the scenes coming out of his native Jacksonville, including a grim photo of a flooded hallway in his former middle school. For so many North Carolinians, recovery will be the new normal for a long time to come.

So it happened that the tragedy of Florence gave our work a renewed urgency and purpose. What a sacred opportunity: to celebrate North Carolina, in a time when she is suffering, to uplift her, to remind the world what her people have given, how they have fed and freshened and fixed our culture with their music.

We urge Oxford American readers to support the ongoing rebuilding efforts in the wake of Hurricane Florence and of Michael, which followed three weeks later. This place and her people have seen fire and rain before. They’ve always come back singing.

North Carolina, we love you.

—Maxwell George

1 “LIGHTS IN THE VALLEY” (LIVE)

Joe & Odell Thompson

We played the same tunes over and over, and Joe never instructed in so many words. If we were getting it right, he kept playing. If we weren’t, he’d stop and say, “You know, I believe we’re going a little fast” or “a little slow,” and we knew to pay closer attention. Then we’d start it up again. We listened, and played, and listened, and played, and one day we were playing with him, and we finished a tune, and Joe turned to our audience and said, “So what do you think of my band?” We looked at each other and knew those were the best words of praise we’d ever, ever get from him. And the only ones we’d ever need.

Read Rhiannon Giddens’s essay on this song.

2 “MY HEART IS FREE”

Tift Merritt

I

nspired by a relative who volunteered for the French army in World War I, “My Heart Is Free” showcases Tift Merritt’s talent for storytelling, which she honed studying the works of Eudora Welty. Merritt’s lyrics, like all good lyrics, have the extraordinary ability to speak to both the universal and the particular. “I was sure there was a reason to take that side and fight / But when I saw the trembling hands that put that shot in flight / I saw the hands of Jesus, saw the shores at Normandy” conjures the individual experience of her relative while speaking to the ubiquitous war-story themes of love, loss, and reckoning. Adding to the narrative is a multi-textured production in which Merritt’s acoustic Gibson underpins the track while the appropriately aggressive guitar parts of Doug Pettibone and Charlie Sexton drive the song to the tragically gained freedom at its core. At every level it’s love and it’s war. And it’s happening all at once.

—The Editors

3 “JOHN HENRY”

Etta Baker feat. Taj Mahal

I n “That Chord,” a Points South essay from this issue, Rebecca Bengal returns to Morganton, her hometown, to reacquaint herself with Etta Baker, the famed Piedmont picker, whom she resisted the lure of throughout her adolescence. Bengal visits Baker’s home and the ephemera she left behind after her death in 2006. It was a conversation with Taj Mahal that inspired the title of Bengal’s piece and most acutely sums up Baker’s musical legacy: that chord!

Though Baker did not become a professional musician until her eighties, early field recordings of her guitar playing were influential not only to Taj Mahal, but to Bob Dylan, who mimicked her style on “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.” In the mid-nineties, she partnered up with the Music Maker Relief Foundation, which was established to help “preserve the musical traditions of the South.” The organization introduced Baker to Taj Mahal, gifted her with quality instruments, and recorded the Railroad Bill sessions and Carolina Breakdown, a record with her sister, Cora Phillips. It’s clear from listening to “John Henry,” which showcases Baker’s crisp slide-playing—often performed with a jackknife—that hers is music worth preserving.

—The Editors

In the magazine: Rebecca Bengal on Etta Baker.

4 “GO WHERE I SEND THEE”

Mitchell’s Christian Singers

In the early decades of the twentieth century, blues, jazz, and r&b arose from a complex gumbo of African-American field hollers, church hymns, folksongs, and rhythmic cadences from the old country. These threads can all be heard in the music of Mitchell’s Christian Singers from Kinston, North Carolina. An a cappella quartet of churchmen, they worked during the week in construction, tobacco, and the like, which meant they rarely performed outside the vicinity of Kinston. But they recorded eighty sides between 1934 and 1940, a catalog that serves as a revealing snapshot of the era when the rural spirituals were turning into a more sophisticated style of gospel on the way to r&b, doo-wop, and soul.

J. B. Long, a white man who ran United Dollar Store in Kinston, discovered the singers in 1934 while seeking a group to record a “disaster song” (a then-popular genre) about a recent train collision in Lumberton. So Long, who would later discover and record Durham blues legend Blind Boy Fuller, set up a contest—two, actually, this being the Jim Crow South. And while the white Cauley Family got to record “Lumberton Wreck,” the African-American Mitchell’s Christian Singers had the more notable career, highlighted by an appearance at the 1938 From Spirituals to Swing concert at New York’s Carnegie Hall, organized by John Hammond.

Mitchell’s Christian Singers’ version of the old spiritual “Go Where I Send Thee” sounds like a call-and-response you might have heard during harvest time, rising and falling like waves of summertime cicadas at dusk. It’s a whimsical countdown, almost in the style of a sing-song nursery rhyme (“A-one for the little bitty ba-by, was born, born, born in a-Bethlehem . . .”), with an intricate arrangement. They recorded it on August 7, 1940—their final time in a studio.

—David Menconi

5 “DON’T PLAY THAT SONG (YOU LIED)”

Ruby Johnson

I hear people speak of worlds of hurt, and I’m not dumb enough to doubt the endless stripes of suffering, especially when the hurt is in the heart. But listening to Ruby Johnson has convinced me that there might be only two kinds of heartache. The first is less an emotion than a paralysis. It takes hold. It locks your door, and then your jaw: it will not let you eat, though it will keep your glass topped off and light a cigarette from the near-filter of another . . . Then there’s the stripe of love-sickness where you’re not even sure it’s hurting. The pain often masquerades as energy, even optimism, yet there is always, in Johnson’s phrasing—in the way she hesitates against the beat—the hint of denial and delusion, and the suggestion, in those seconds where her voice rises and cracks, of trouble ahead.Read Michael Parker’s essay on this song.

6 “DON’T LET YOUR DEAL GO DOWN” (LIVE)

Earl Scruggs, Doc Watson & Ricky Skaggs

G

rowing up in Boiling Springs, North Carolina, it was inevitable that Earl Scruggs and his music were a part of my daily life. I went to school with Earl’s nephew, Elam; worked during my summers for Earl’s brother, Horace (a fine musician in his own right); and attended the “homecomings” when Earl and his sons Randy and Gary would perform for us. Earl’s music was on the local radio stations, on the jukebox at the town’s one restaurant, and on our homes’ record players. Even our humor reflected Earl’s presence in our lives. (“Anyone can sing Flatt, but only Earl can play Scruggs.”)

One of the best aspects of this version of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” is that Scruggs is playing with Doc Watson, another folk music pioneer from Western North Carolina. Earl’s banjo opens the song and, like mica in a sunny mountain stream, gives the song a glittering brightness it retains throughout. Doc’s guitar and vocal mesh perfectly, as does Skaggs’s mandolin, but the tune begins and ends with Earl. The song runs only two minutes and twelve seconds, but the genius of the musicians is fully revealed.

A few years ago, I was in Wellington, New Zealand, for a book festival. As my event was about to begin, I heard a familiar banjo. The song was “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.” Afterward, I thanked my session host for choosing a song performed by someone from where I’d grown up. “Oh,” she said, a bit embarrassed, “I didn’t know that; the song just seemed right.” I couldn’t have asked for a better compliment.

7 “PRETTY SARO”

Cas Wallin

There are countless “Pretty Saro”s and variants thereof on both sides of the Atlantic. It might be Irish in origin. Or it’s English. Or it’s native-born, in Virginia. Either way, it’s a song nimble enough, in both tune and theme—exile from love and home—to bend without breaking in its own passages roaming to and fro across the sea, and across the Appalachian and the Ozark Mountains, accumulating or casting off era- or site-specific details as its singers have seen fit. It’s been doing so for well over the last two hundred years.

The English song-collectors Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles found several strands of it in Western North Carolina when they visited in 1916 hunting for Old World ballad “survivals.” The pair collected some one hundred songs in the mountains of Madison County, at the center of which is a tiny community called Sodom Laurel that, pound for pound, has produced more gifted traditional singers than anywhere else in America. Dillard Chandler, Dellie Chandler Norton, Lloyd Chandler, Berzilla Wallin, Sheila Kay Adams, and Cas Wallin all came from Sodom Laurel, yet somehow each of them developed a singing style very much their own, each imbued with a particularly profound emotional resonance that could frequently approach transcendence.

Cas Wallin was not the best singer in Sodom, nor the most prolific, but he didn’t need to be, as the “Pretty Saro” that he sang is tuned to perfect pitch. There is no other extant text of the song honed so smoothly against the stone of time and tradition; there is no superfluous sentiment or detail in his singing and no vital one missing. No performance I know of embodies so exquisitely the lingering ache of a lover long lost, and no singer expresses it with more delicately devastating resignation: “I once loved her dearly / and I don’t hate her now.”

8 “HEY MIAMI” (MOOG SOUND LAB)

Sylvan Esso

Durham-based duo Sylvan Esso travels light. A microphone. A laptop. A controller. Maybe a small synth or two. Vocalist Amelia Meath and producer Nick Sanborn met on the road while members of different bands, and Meath moved from Brooklyn to Sanborn’s adopted North Carolina in the band’s primordial days, where they perfected their brilliant mixture of pop and electronic music, all written with a soul and feeling that could belong to any age. This live reinterpretation of “Hey Mami,” the first track from their debut album, was recorded in those early days, in 2013, at the Moog Sound Lab in Asheville, in the home of the most famous synthesizer company in the world. With cameras rolling, Sylvan Esso reconstructed their song on the fly, using an array of massive rack-mounted analog synthesizers and effects units behind them. Each snare, kick, and hi-hat is custom built out of nothing but oscillating analog noise. When the drop arrives, the bass slides up and down as if controlled by an alien force, filtered through the numerous pulsating devices.

Moog, after all, has its own famous Carolina transplant story—synthesizer pioneer Robert Moog moving his production and headquarters to Asheville from New York in the 1970s. As Moog synthesizers took over music, and electronic music later took over the world, North Carolina found itself an unlikely magnet for those who wish to sculpt sound out of machines. The Durham festival Moogfest is one of the largest of its kind, bringing in artists and technologists from around the globe. Companies like former Moog employee Tony Rolando’s Make Noise, a pioneering maker of new-school eurorack synthesizers, also call North Carolina home, building contraptions that shake the walls of Berlin, Tokyo, and New York every night. That sound you hear that sounds like nothing else? There’s a good chance the machine responsible for it was made in North Carolina.

—Maxwell Neely-Cohen

9 “OH MY LOVE” (DEMO)

The Teentones

In “A Teentone in Rome,” a Points South essay from the issue, Jon Kirby retraces the little-known story of Wesley Johnson, a Winston-Salem native who carved out an unlikely, vibrant r&b career in Italy beginning in the sixties. Before moving abroad, in grade school, Johnson and his friends formed a band they dubbed the Teentones and dreamed of soul stardom. Hoping to woo national record labels, they cut a one-take acetate demo at a local recording studio in nearby Greensboro, featuring a single guitar, a bass, and a makeshift guitar-case hand drum. As Kirby writes, “The result was a lo-fi, ten-song testimonial as to why the Teentones deserved to sing from a platform more prominent than the Piedmont could provide.” It wasn’t to be; the group disbanded after high school, and before long, Wesley was touring Europe.

Wesley Johnson was the Teentones’ frontman and guitarist, but on the beachy, moody, and blue original number “Oh My Love,” his best friend Carl Johnson took the lead. When the Oxford American reached out to the latter for permission to include this previously unreleased recording in our North Carolina Music Issue, he was excited, if incredulous. “I never dreamed someone would come approach me about this,” Johnson said. “It’s been almost sixty years.”

In the magazine: Jon Kirby on the TeenTones.

10 “THE QUESTION IS HOW FAST”

Superchunk

By the time this song came out in January of 1993, Superchunk had been a band for about three and a half years, and Mac and I had been running Merge and playing in Superchunk for pretty much the same length of time. It seemed like an eternity. Ha! In July of 2019 we will have been doing this for thirty years. But let me back up for a minute.

In the mid-eighties my parents split up, and when I was a rising senior in high school, my mother moved us from Atlanta to Raleigh. I was a citified goth and was not pleased. (I had been born in Charlotte and spent some of my childhood in North Carolina, but Atlanta was where I had lived the longest of anywhere in my young life.) As I saw it, Raleigh was a redneck backwater where my punk-rock lifestyle was going to be stifled, or at least challenged in ways I was not used to. What I discovered was a homey “scene” (as we called it) grounded in a shared love of music, conversation, and community that spanned the Triangle. We were a family of misfits and outcasts bound together only by the fact that we all felt out of place in the “normal.” There weren’t enough freaks around for there to be divisions or factions. Punks, goths, skins, mods, and even hippies all got folded in together.

More incredibly (to me), any of them seemed to feel they had the right to form a band at the drop of a hat, whether they had any experience playing an instrument or not. There were some great bands and some less great bands, but none of that mattered. They were fun art projects with no purpose or intent other than to entertain us and our friends. Pass the time. It was this kindness and celebration of otherness and creativity that allowed me to slowly blossom into a member of a band and eventually start a record label so we could document little snippets of this beautiful scene. Many times over the years I have realized how grateful I am for that move that I resisted with such fervor. Thank you, North Carolina, for taking me back in.

—Laura Ballance

11 “YOU DON’T COME SEE ME ANYMORE”

Malcolm Holcombe

It must have been 2004 when I first heard him, A Hundred Lies dropped in my hand by an old Southern Lit professor down in the failing hills of South Carolina, where I grew up. It was, and still is, a land of red clay and waterfalls and shuttered textile mills gone to the Maquiladora belt of Mexico, of Sunday suppers in the mosquito heat. Sticking that CD into the deck of my ’89 Jimmy, I knew, I simply knew I was listening to a truth that, though it was all around me, I had never quite heard articulated outside of books. I’ve been listening to him ever since, but until tonight I’d never met him.

Read Mark Powell’s essay on this song.

12 “BIG-EYED RABBIT”

Samantha Bumgarner & Eva Davis

J

ackson County, North Carolina, in the midst of the Great Smokies, was home to Samantha Bumgarner and Eva Davis, native musicians who traveled to New York City in April 1924 to record their “old-fashioned southern songs and dances” on fiddle and five-string banjo, as reported in the trade journal Talking Machine World. They are now hailed as the first women to record country music, three years before the industry’s canonized “big bang” of 1927. Playing to a large acoustic horn in the studio, Bumgarner and Davis waxed a set of vintage ballads, blues, and breakdowns. Among their ten issued sides was “Big-Eyed Rabbit,” a playful dance number inspired by a rabbit hunt, delivered as a rhythmic chant well-suited to the subject matter. In other words, it hops.

“Aunt” Samantha Bumgarner lived by the Tuckasegee River near the town of Sylva, and she often entertained at area schoolhouses, passing out handbills that promised “a soul-stirring, blues-killing and jolly good time for all.” In 1928, she took part in Asheville’s first annual Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, organized by Bascom Lamar Lunsford, and she remained a fixture at that event for the next thirty-one years. At the 1936 festival, her banjo playing sparked a lifelong passion for the instrument in a young attendee named Pete Seeger. In 1937, she spent four weeks in Del Rio, Texas, broadcasting over radio station XERA, a “border blaster” owned by Dr. John R. Brinkley, notorious quack and fellow Jackson County native. Bumgarner’s death at age eighty-two on Christmas Eve 1960 ended a long and colorful career.

But what of Eva Davis? On July 5, 1924, she and Samantha performed live at the Music Department of Sterchi Brothers Furniture in Asheville, billed as “Two New Columbia Artists from Sylva, N.C.” On sale were their first two releases, including “Big-Eyed Rabbit.” After the in-store appearance, however, the trail goes cold. A search of newspapers, census records, and court documents yields no credible leads. Even the Jackson County Journal failed to mention her when it reported Bumgarner’s recording trip to New York. Perhaps, if we’re lucky, a descendant will someday unveil a trove of photos and keepsakes that shed light on Eva Davis, half of the two-woman team that made music history all those years ago.

—Marshall Wyatt

13 “TAKE MY BABY TO THE DOCTOR”

Big Boy Henry

“I

saw the studio time as a chance to capture as much as possible, to allow the ease of time to call forth whatever Big Boy Henry wanted to say, play, or sing for the archive, for the lasting record,” documentarian Tom Rankin recounts in “Art Like Any Other Music,” a Points South essay from this issue. Henry was a menhaden fisherman, preacher, and blues guitarist and singer from the small coastal town of Beaufort, North Carolina. His most famous song was his 1983 protest of Reaganomics called “Mr. President,” in which he asks, “Will you reconsider? / It’s bad out here, man, it’s tough / People are suffering all up and down the line,” and offers to give Reagan a firsthand tour of the poor person’s marginal struggle. Toward the end of his life, Henry was supported by the Music Maker Relief Foundation, which released his final album in 2002, Beaufort Blues.

This previously unreleased recording comes from Rankin’s archive at the Southern Folklife Collection at UNC Chapel Hill. Across two days in the studio at WUNC in 1982, Rankin captured hours of tape of Henry’s stories and songs. “Take My Baby to the Doctor” is a signature display of Henry’s fluidity with the improvisational talking blues style, in an autobiographical song about his wife’s recent illness and his unwavering faith in God’s plan.

—The Editors

In the magazine: Tom Rankin on Big Boy Henry.

14 “STREETS OF GOLD”

Lumbee

Lumbee songwriter, singer, and guitarist Willie French Lowery was born in 1944 to a cotton-farming family in rural Robeson County, which is North Carolina’s largest county geographically and often its poorest, then tri-racially segregated into white, black, and American Indian communities. As a young musician he traveled with a carnival, playing guitar for the “hootchie-cootchie women,” and served as bandleader for former Drifter (and fellow North Carolinian) Clyde McPhatter.

“Streets of Gold” ostensibly posits a spiritual certainty about the afterlife—Lowery’s soulful voice rasps with abandon about angel bands in a celestial El Dorado—but listen more closely and you can hear the seeds of gnawing doubt that render this swamp-psych psalm so indelible. Faith arises from “the midst of a mass confusion,” where “everybody got a different illusion of what is right.” The first sound we hear from Willie is a ductile, dilatory scream of denial: “No-no-no-no-no-oo-oo! ”

His band’s origins were similarly characterized by ambivalences and ambiguities. Lumbee was the second incarnation of pioneering interracial group Plant and See. The band borrowed its new name from Lowery’s tribe—the largest American Indian tribe in North Carolina and the largest east of the Mississippi. He proudly counted himself a member of the tribe, but the choice of the name Lumbee for the band was his reluctant, reappropriative response to their new label’s ignorant suggestion that they rebrand themselves “Cherokee.” “When we changed the name of the group to Lumbee, I became an Indian again,” Willie slyly told me. (To his chagrin, the label packaged Lumbee’s sole album, Overdose, with a shamelessly provocative drug-dealing-themed board game, queasily associating the tribal name with hippie sensationalism.)

“Streets of Gold” became the most commercially successful song of Lowery’s career, charting in various East Coast markets in 1970. The same year, Lumbee played with the Allman Brothers at the Love Valley Festival, North Carolina’s answer to Woodstock, and the two bands toured together thereafter. In 1979, Lowery released a solo record called Proud to Be a Lumbee, the title track of which has become the unofficial national anthem of his tribe. “‘Activist’ is the most beautiful word in the English language,” Willie often said. He died in 2012, following a long battle with Parkinson’s disease; inscribed on his gravestone is the legend “WALKING ON THE STREETS OF GOLD.”

—Brendan Greaves

In the magazine: Malinda Maynor Lowery on Lumbee.

15 “HOLY GHOST, UNCHAIN MY NAME”

Elizabeth Cotten

Folk music is one of the original outsider art forms not by accident. A particularly biting portrait of our world is that Cotten was discovered while keeping house for Mike and Peggy Seeger in Washington, D.C. By then she was a grandmother, a longtime domestic worker who, in her spare time, picked the guitar, made up songs, and sang other songs she loved. She was the first person to play legendary McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica, taking up touring in her sixties when many musicians would likely retire if they could. In film, you can see her comment with some real astonishment that the Seegers did the dishes and just asked her to sing. The sound of her life—her humility, her heart and all its everyday miles—makes her guitar ring the way it does. She birthed us all with her plainspoken truth and there is no way to fake that.

Read Tift Merritt’s complete essay on this song.

16 “AFRICAN MAILMAN”

Nina Simone

By the time Nina Simone, twenty-four, entered the studio in 1957, she had moved from North Carolina to New York; enrolled in the Juilliard School; accepted a regular gig at the Midtown Bar in Atlantic City; started lessons with classical pianist Vladimir Sokoloff; and made a demo that caught the notice of the owner of Bethlehem Records. Her session lasted only fourteen hours, and she composed “African Mailman” on the spot and recorded it in one take. “I went into the studio and recorded my songs exactly as I always played them, so when you listen to that Bethlehem album you’re hearing the songs played as they were at the Midtown Bar,” Simone wrote in her autobiography, I Put a Spell on You. The album, Little Girl Blue, came out in 1958 (a “good new talent here,” proclaimed the writeup in Billboard; as it turned out, “African Mailman” was excluded from Little Girl Blue and later released on the album Nina Simone and Her Friends). That year, she’d have her first hit with “I Loves You, Porgy.”

Though today Nina Simone is best known for her protest anthems and passionate stage performances, this jazzy number takes us back to the very start of her career, before she was an icon or civil rights activist. In “Nina Is Everywhere I Go,” a feature in this issue, Tiana Clark traces Simone’s origins even further, to the “wild weeds and the creaking wood on the front porch” of her childhood home in Tryon, where she first heard jazz standards and studied Bach and Beethoven. Clark, a poet, makes a pilgrimage to North Carolina, tracing her own family’s history and seeking the essence of an artist who has also been her muse. She searches for Simone and learns about herself, and the High Priestess of Soul feels even more relevant—and present—than ever.

—The Editors

In the magazine: Tiana Clark on Nina Simone.

17 “CHROME (LIKE OOH)”

Rapsody

“I’m real,” Rapsody asserts in the closing bars of “Chrome (Like Ooh).” “Represent, where you from?” a chorus asks in return, and the confident answer is “Snow Hill.” For Rapsody (Marlanna Evans), the small Eastern North Carolina town and tight community she was raised in has been an enduring source of strength and inspiration as her international recognition has grown. For “Queen of Snow Hill,” L. Lamar Wilson spent a day in July touring with Rapsody around her hometown and talking about family, fame, and her influences, most prominently Lauryn Hill and her fellow North Carolinians Nina Simone and 9th Wonder.

On this standout track from her Grammy-nominated album Laila’s Wisdom, Rapsody muses about her stature in the rap game. But despite the chrome and all the other trappings of success, she maintains humility and purpose: “Taught to respect the driver more than I do the ride,” she raps. The intricate beat is supplied by 9th (Patrick Douthit), the producer extraordinaire, professor, and Jamla Records label head profiled in a deature in this issue by Dasan Ahanu, “Make Me Hot P, Hold Me Down P”. Between Rapsody and 9th in Raleigh, plus superstar J. Cole’s commitment to his native Fayetteville, North Carolina’s immense influence on hip-hop is no longer just a hot take. Raise up.

—The Editors

In the magazine: L. Lamar Wilson on Rapsody.18 “WHAT WILL I DO?”

Vernon, Doug & Link Wray

In his thoughtful story about the masterful guitarist Link Wray, John O’Connor’s feature from this issue, “Mystic Chords,” both rescues Wray from the notoriety of his 1958 hit “Rumble” (which earned him the title “inventor of the power chord”) and rightfully restores him to the full context of his long collaborations with his talented family, namely brothers Vernon and Doug. “The Wrays had an old-world, Keatsian melancholy,” O’Connor writes. “It bloomed in the kitchen of their 6th Street home in Portsmouth, Virginia,” where the family had moved, following work, from Dunn, North Carolina.

The lament of “What Will I Do?”—a homemade demo from around 1952–53 released here publicly for the first time—captures the simple pain of love lost, with Vernon crooning the lead vocal, and is all the more luminous for the ordinary background sounds washing through the music. Sherry Wray, Vernon’s daughter, found a collection of one-track recordings in a box stashed away by her late dad—a box bound for the trash—and shared them with the Oxford American. “When I saw your interest in ‘What Will I Do?,’” she wrote, “I was a little teary-eyed. It features all three brothers singing that sweet harmony and my baby brother, now passed away, crying during the session.” The song and the sentiment are worthy of Keats: “Sweet voice, sweet lips, soft hand, and softer breast, / Warm breath, light whisper, tender semi-tone.”

—The Editors

In the magazine: John O’Connor on Link Wray.

19 “COPPERLINE” (LIVE)

James Taylor

“‘Copperline’ is a photo album snapshot that harkens back to my childhood,” James Taylor told biographer Timothy White. “None of it is real accurate—but none of it is inaccurate, either.” Will Blythe, who, like Taylor, grew up in Chapel Hill, expands on that snapshot in his Points South essay from this issue, evoking the progressive milieu and midcentury-modern houses, the trees and rock formations, “the briars, the vines, the sprigs of miniature swamps” of the beguiling college town where the famed singer-songwriter came of age. (Taylor fans will burn with envy at Blythe’s recounting of an indelible Christmas gathering attended by two unassuming yet remarkably gifted carolers.)

In 1991, Taylor co-wrote “Copperline” with his friend Reynolds Price, the great North Carolina writer, “perhaps the first significant American novelist to compose a successful Top 40 popular song,” posits James A. Schiff in Understanding Reynolds Price. At the start of this live recording, made at the Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in 2007, Taylor says, “Here’s another song about North Carolina.” He paints a North Carolina of summer nights, wood smoke, moonshine, first kisses, and the creek where he grew up. It is a tantalizing vision.

—The Editors

In the magazine: Will Blythe on James Taylor.

20 “MILL MOTHER’S LAMENT”

Ella May Wiggins; Performed by Shannon Whitworth

After speaking, Ella would launch into one of her protest songs. She wrote and performed several original ballads during the strike, but ‘Mill Mother’s Lament’ was her best known. Based on the melody of the popular song ‘Little Mary Phagan,’ it portrays the heartrending plight of Southern mill mothers and their children. Ella had grown up in the Smoky Mountains, first on farms and then in lumber camps, where she and her mother took in laundry while singing old mountain ballads. According to accounts, Ella’s singing voice was deep and seasoned with pain, and her lyrics reflected the plainspoken style of her speech.

Read Wiley Cash’s essay on this song.

21 “ME OH MY”

The Honeycutters

If I’d been asked, I might’ve said I was held hostage, and truthfully I kind of was. Platt sang and her voice sank its claws into me and I didn’t move. One song bled into the next and I sat there until she was finished. I would’ve sat there for days if she’d kept singing. When the show was over, I pulled out what little money was in my wallet and shoved those crumpled bills in a jar by the stage for the only album the Honeycutters had at the time, a record called Irene. I played that record on a loop for months. I’ve bought every album they’ve recorded since.

Read David Joy’s essay on this song.

22 “SOMEBODY ELSE’S WORLD”

Sun Ra & His Arkestra

Sonny (as Sun Ra was called by some) and June, dueting in their black angel costumes of capes and sequins and spandex, were some of the diaspora’s first images of another kind of black spectacular: one that relentlessly defines itself. Yet while Sun Ra’s sidemen, Marshall Allen and John Gilmore, are still discussed in detail and with reverence among scholars and fans, information on June is cryptic and sparse. She is all but exiled from the kingdom of jazz singers, not traditional enough as a muse to be remembered as a musician.

Read Harmony Holiday’s essay on this song.

23 “GOODBYES”

Alice Gerrard

Seattle-born, California-bred, Washington, D.C.–affiliated Alice Gerrard was already a folk and bluegrass icon by the time she moved to Durham in the eighties, where she founded the Old-Time Herald, the celebrated journal devoted to traditional American music, especially that of the South. (It is still in publication today.) After serving as Gerrard’s graduate teaching assistant for a class she taught at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke called “Documenting Tradition,” folklorist and singer-songwriter M. C. Taylor (better known by his musical alias Hiss Golden Messenger) proposed producing a new record of her music. Also a California native, Taylor had discovered a deep fellowship in the vibrant, communal music scene, where locals embraced transplants. To back up Gerrard on the album, he enlisted some friends, including the Wisconsin brothers Phil and Brad Cook (DeYarmond Edison, Megafaun), themselves musicians who had been adopted by the Triangle.

The resulting album, Follow the Music, a collection of reinterpreted traditional songs—including a warm rendition of North Carolina fiddle legend Tommy Jarrell’s signature tune, “Boll Weevil”—and powerful originals, earned Gerrard a Grammy nomination at age eighty. Speaking with Amanda Petrusich for the Oxford American in 2013, Taylor commented on the power of folklore, the shared interest that had drawn both him and Gerrard to the South and to one another: “What’s beautiful isn’t the big flash. It’s the small things.” On her album’s transcendent closing track, “Goodbyes” (written by Gerrard’s grandson), we first hear a laidback, acoustic lull before Gerrard’s voice arrives on wings of experience and empathy, freighting a small thing with a beauty for the ages: “Don’t, don’t you hate goodbyes? / Don’t, don’t you never want to say goodbye again?”

—The Editors

24 “CREPUSCULE WITH NELLIE” (TAKE 2)

Thelonius Monk feat. John Coltrane

“Why do we remember the past but not the future?” Stephen Hawking once asked, famously.

1957 was a very good year.

Rocky Mount met High Point. In New York. The Grand Griot of the saxophone alongside the Niels Bohr of Jazz. Here tempo, tension, expectation are not only frustrated, but Monk distorts time while at the same time being in time. Or as my uncle who taught me about jazz once said, “That brother was playing all up in the cracks of that piano.” Places we don’t see or hear.

“Crepuscule with Nellie.” Crepuscule (twilight). Monk always with his bedeviling, whimsical, elusive, elliptical titles. Hiding in plain sight. A walk at dusk with his future wife. According to his biographer, Robin D. G. Kelly, this was Thelonious Sphere Monk’s only composed piece. No improvisation. Deliberate. Like Schubert.

Midway, the Trane swoops in with his magic saxophone, rather like an archangel hovering, in support, but also adding color and human gravity to a musical quadratic equation. North Carolina brother backing up North Carolina brother. Visionary seeing into Visionary. Remembering the future together.

This is the Doppler effect of jazz. From a distance we are watching light bend and divide and break up and spread out as it comes back together. Dusk is made dawn.

In the magazine: Benjamin Hedin on John Coltrane.

BONUS TRACKS

“LAND OF THE SKY”

Don Clayton

“Land of the Sky" is a catchy number celebrating all things Asheville—with shoutouts to the city’s beloved music venue the Orange Peel, various breweries from its nationally recognized local beer industry, and, of course, the Biltmore Estate. Asheville’s music scene isn’t as well known as the Triangle’s, but Clayton’s song, recorded recently at Echo Mountain with help from a diverse collection of local musicians, aims to change that.

“MORNING AFTER COFFEE”

Kelsey Lu

A classically trained cellist turned singer-songwriter, Kelsey Lu was born into a family of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Charlotte (her father was a percussionist in the seventies funk outfit Fungus Blues Band). Lu found her calling at the North Carolina School of the Arts in Winston-Salem before relocating to New York. In 2016, she recorded her debut EP live in a church, looping her cello and vocals.

“ONE MORE TIME”

Salty Miller

The former leader of the sixties UNC Chapel Hill beach music group the Monzas, Salty Miller enlisted a supergroup of beach music veterans—including members of the Embers—to record a new collection of songs in 1980. The moody, nostalgic ballad “One More Time” features the sounds of seagulls and ocean waves sourced from the Carolina coast.

In the magazine: Jill McCorkle on beach music.

“OJOS BOBOLOS”

Chócala

This track from the group’s 2017 debut EP en[demo]niá is about the desire for change,” lyricist Liza Ortiz says. “The first few lines I wrote were: ‘Is it a crime to want to see my people with a house, food and faith on their minds, that all of their dreams can come true, and they don’t have to flee from hope.’ My hope for this song is to convey the community effort and will for change.”

In the magazine: Lina María Ferrerira Cabeza-Vanegas on Chócala.

Liner Notes Contributors

Laura Ballance is the bassist for Superchunk and cofounder of Merge Records. She lives in Durham.

Brendan Greaves is the cofounder and owner of the Chapel Hill record label Paradise of Bachelors. He curates and writes about vernacular art and music in the American South and beyond.

Randall Kenan is the author of a novel, A Visitation of Spirits, and a collection of stories, Let the Dead Bury Their Dead, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. He teaches at UNC Chapel Hill.

David Menconi is music critic and arts reporter at the Raleigh News & Observer. He is currently working on a history of North Carolina music, to be published by University of North Carolina Press.

Maxwell Neely-Cohen is a writer living in New York City. He is the author of the novel Echo of the Boom.

Ron Rash is the author of The Risen and Serena, in addition to five novels, five collections of poems, and six collections of stories. He teaches at Western Carolina University.

Nathan Salsburg is a guitarist, a producer, and the curator of the Alan Lomax Archive.

Marshall Wyatt is a Grammy-nominated producer and the founder of Old Hat Records in Raleigh.

The Oxford American’s 2018 Southern Music Issue – North Carolina sampler would not have been possible without the generosity of the creators and rights holders of these songs. Editorial liner notes written by Eliza Borné, Maxwell George, Jay Jennings, and Sara A. Lewis.

Order the North Carolina Music Issue & CD.

- Liner Notes

- North Carolina

- Music

- Music Issue

- Issue 103

- Joe and Odell Thompson

- Tift Merritt

- Etta Baker

- Taj Mahal

- Mitchell's Christian Singers

- Ruby Johnson

- Earl Scruggs

- Doc Watson

- Ricky Skaggs

- Cas Wallin

- Sylvan Esso

- The Teentones

- Superchunk

- Malcom Holcombe

- Samantha Bumgarner

- Eva Davis

- Big Boy Henry

- ELizabeth Cotten

- Ella May Wiggins

- Shannon Whitworth

- Lumbee

- Nina Simone

- Don Clayton

- The Honeycutters

- Rapsody

- Vernon, Doug, & Link Wray

- James Taylor

- Kelsey Lu

- Sun Ra

- Alice Gerrard

- Thelonious Monk

- John Coltrane