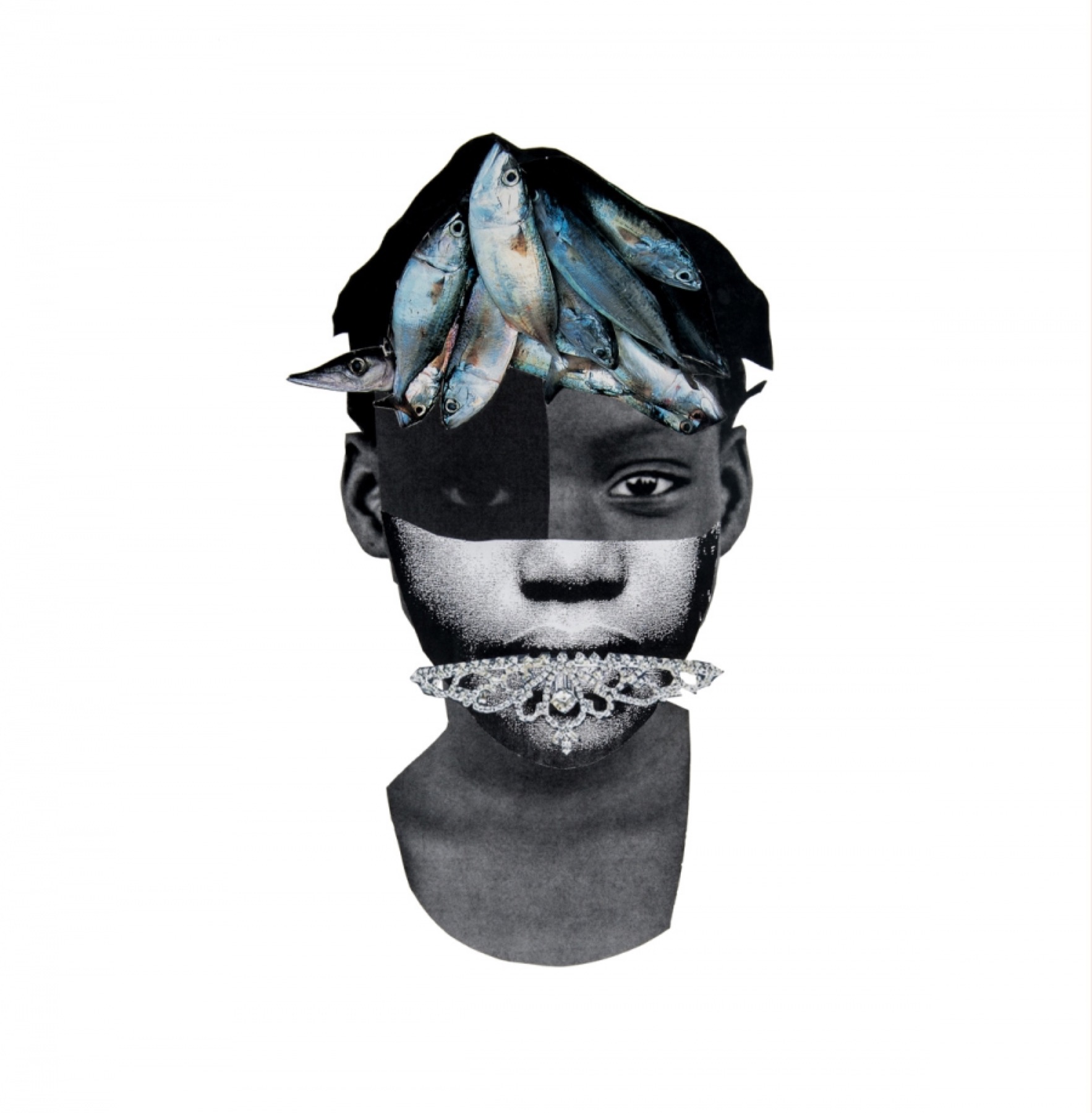

“Grillz, Don’t pee on my head and tell me it’s raining [fish]” (2017), by Deborah Roberts, from the series Not on Me. Courtesy of the artist

Queen of Snow Hill

Rapsody on top in hip-hop—and at home

By L. Lamar Wilson

It’s Grammy night 2018. The year’s requisite male nominees for Best Rap Album—Jay-Z, Kendrick Lamar, Migos, and Tyler, the Creator—smile with anticipation as the sole female contender admires a projection of her mien on Madison Square Garden’s massive screens. A red undercut bob makes Rapsody’s caramel face and chestnut eyes radiate all the more under the bright lights, eyes she’s had to learn to love after years of jeers from trolls who don’t understand what Graves’ disease does to them, to an athletic black woman’s body, her self-esteem, her sense of magic. “I go so hard / Make the whole world love me,” she vaunts on “Black & Ugly,” arguably the most celebrated track on Laila’s Wisdom, the album she named after her maternal grandmother, a contemplative, sage soul like herself. Her sophomore album has landed her firmly here—finally!—on the main stage where she belongs with the best of the best. Her ascent has been a decade in the making, inspiring Hov himself to show her love through a deal his Roc Nation management company has brokered with her label, Raleigh’s Jamla Records.

To the larger world, Marlanna “Rapsody” Evans came rushing out of nowhere like a breath of fresh air in a dank field of female MCs, where rumors of butt injections, baby-daddy drama, dis records, Twitter beefs, and Fashion Week fisticuffs too often taint discussions about women’s flow and relevance, where lyricists of substance get labeled “conscious” and thus niche. Not Rapsody. She’s been slowly building her cred as Jamla’s wunderkind, guided by super-producer and hip-hop scholar Patrick “9th Wonder” Douthit, grindin’ around the world while holding fast to the values she learned from Mama Laila, her parents, and her vast family, which includes four siblings, a dozen aunts and uncles on her mother’s side alone, and a cadre of cousins. Many of her kin still reside in Snow Hill, a town of roughly two thousand in North Carolina’s Coastal Plains region, full of tobacco farms and open fields, jukes and corner stores, a penitentiary, and a smattering of churches. The DuPont plant in nearby Kinston employs many residents; Rapsody’s father, Roy, worked there as a mechanic for years.

Watching her mother, Margaret Evans, an artist at heart, surrender her dreams to assembly-line work in any number of industrial jobs in the area—dyeing ribbons for Snow Hill Tape for years, now painting the accents on Lenox China’s luxury offerings—Rapsody cultivated a resolve that’s shaped her path to independence and artistry outside the rubric of high-end-label name-droppin’ and vagina-monologuin’ for the gaze of men and the delight of marginalized queer communities hankering for a diva to worship and emulate. With verses rooted in Alice Walker’s womanist tradition of self-reflexive ode, cautionary tales, and homage to elders and ancestors, Rapsody foregrounds the work of her mind in an industry that’s thrived on selling black women’s blues, capitalizing so much on their music about being treated badly—like “the mules of the Earth,” Zora Neale Hurston wrote famously in Their Eyes Were Watching God—a business that demands so much labor of their bodies and offers so little to compensate for the emotional toll playing the part takes.

The camera cuts back to the award’s presenter onstage in the Garden. “And the Grammy goes to,” Dave Chappelle intones, “DAMN. Kendrick Lamar.”

Unlike some of the nominees, Rapsody’s smile doesn’t fade or strain. “To hear my name called out amongst them, especially Jay and Kendrick,” Rapsody later reflects, “you think, whether you win, I am—and I was—just happy to be there. Then they announced that Kendrick won, and I was still happy. I mean, that’s my friend. He’d made a great album.”

A soon-to-be Pulitzer winner, in fact. But it’s not hard for Rapsody—Rap or Marlanna to friends and family—to celebrate her friends’ successes. Raised a Jehovah’s Witness by hard workers and entrepreneurs, she follows the mantra Mama Laila lived by: “Give me my flowers while I’m here.” That’s why beside her at the ceremony sits her younger brother, Mark, recently home from serving in the Afghan war, which has smoldered alongside the conflict in Iraq for nearly two decades and left the nearly thirty thousand who have returned injured, like him. It’s his turn to enjoy the industry’s big night, just as her mother and older sister, Kenyatta, did when she flew them out to Los Angeles a couple of years prior for that year’s ceremony.

Upon hearing Lamar’s name, she stands without hesitation to salute the man who introduced her to the global stage as “loved one” on “Complexion (A Zulu Love),” a standout cut on his breakout sophomore masterpiece, To Pimp a Butterfly, which earned him six Grammys, including Best Rap Album, one he shares symbolically with Rapsody for blessing the song with its stellar two-minute coda (“When did you stop, loving the / Color of your skin, color of your eyes? / That’s the real blues, baby . . .”).

Rapsody’s journey to this moment began with that verse’s keen slant rhymes, repetition, enjambment, imagery, allusions to alliances across difference, and message of self-love:

The new James Bond gon’ be black as me

Black as brown, hazelnut, cinnamon, black teaAnd it’s all beautiful to me

Call your brothers magnificent, call all the sisters queensWe all on the same team, blues and Pirus, no colors ain’t a thing.

Now that the world’s caught on to what 9th Wonder always knew, she’s boldly sharing “the real blues” and representing the newest generation of artists bringing North Carolina’s special blend of what Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones) heralded in 1967’s Black Music as “racial memory” to the world:

Blues (Lyric), its song quality is, it seems, the deepest expression of memory. Experience re/feeling . . . It is the “abstract” design of racial character that is evident, would be evident, in creation carrying the force of that racial memory.

“What’s coming out of her mouth is the straight metaphors and punch lines and similes and wordplay that a lot of times we don’t even expect in this particular generation . . . females to do,” 9th Wonder explains on the sixth episode of the Netflix series Rapture, which features mid-career artists whose music has begun to influence the masses.

It’s no surprise, then, that Lamar would choose Rapsody’s multivalent, Southern voice to join his as they tackle issues as vast as misogynoir, colorism, and police brutality. She’s been primed for the spotlight all her life. In Snow Hill, she has always been popular, a unifier, chosen as her high school’s homecoming queen and star guard. You only need to watch her meld fierce lyricism with around-the-way-girl grace in the videos for “Sassy” and “Pay Up” and listen to the other tracks on Laila’s Wisdom to see why they snagged shine in the same Grammy nomination categories with DAMN. and 4:44 and had hip-hop heads battling over which of the three was the best hip-hop record of this decade.

Rapsody now dons the mantle for a long tradition of black women, particularly those from the South, forcing Americans to look in the mirror of our professed ideals and to face the ills that haunt us. She carries the torch the outspoken, Tryon-born Nina Simone held high in the heat of the last century’s civil rights movement, before she fled to Europe for respite and asylum. She embodies the quiet fire and sensuality of the diminutive Roberta Flack, born in the Asheville-area town of Black Mountain, whose blend of torch ballads, folk, soul, gospel, and disco transformed what could be decidedly black and land in the genre of “pop music” as the civil rights fight gave way in the latter part of the century to the cultural appropriation that integration wrought. She wields the virtuosity of women like jazz great Mary Lou Williams, whose spiritual recordings released in the late 1970s while she was an artist-in-residence at Duke University in Durham limned all musical genres in the way Rapsody’s sound does. Just as Shirley Caesar has remained Durham’s ambassador for genre-blending gospel since Williams died, Rapsody’s lyrical dexterity has given Snow Hill—and the state—bragging rights on one who’s true to her roots and willing (and able) to take risks that raise the game’s stakes.

America has depended upon black women’s voices to serve dually as sources of balm and booming indictment since slave Lucy Terry Prince started singing “Bars Fight,” honoring European immigrants slain in 1746 in a gruesome massacre near her Massachusetts town, while subtly pointing out the mercy shown by the indigenous Abenakis responsible for the mass killings. It’s reported that she sang so beautifully and memorably that her ballad remained a kind of nursery rhyme for a generation after she died in 1821. In this way, black women’s voices have shaped the American songbook from the nineteenth century’s Negro spirituals and early opera to the last century’s ragtime and gutbucket blues, which birthed various iterations of rock & roll, jazz, r&b, funk, gospel, and today’s growing subgenres of spoken word and hip-hop.

But what is it about North Carolina’s towns—their quietude and mystery—that tuned the ears and cultivated the songcraft of these truth-tellers? And how have Simone, Flack, and Williams shaped Rapsody’s sound? The path to these musical forebears came, she says, while studying accounting at NC State in Raleigh, an hour away from home, where she also studied the catalog of the first woman to win a Grammy for Best Rap Album, Lauryn Hill of the Fugees.

“I got onto Nina more in college, just learning her influence on Lauryn. That’s when you start to dig deeper,” she reflects in her parents’ Snow Hill kitchen in July, as Mrs. Evans prepares an impromptu brunch of eggs, fruit salad, and orange juice. Our meal leads to an hours-long meditation in their living room on music and faith. “I know how much of an influence she was to Lauryn’s artistry and, I’m sure, the woman that she is now, and so that kinda just trickled down the same way you’ll have A Tribe Called Quest’s family. They spawn the Roots, and your Little Brother, and now your Kendrick Lamar—all of them come through that family tree. It just kinda trickled down through the roots.”

Rapsody had followed the educational path blazed by her older sisters at the behest of her mother, who hadn’t wanted her children to spend their lives hanging tobacco or working in factories, prisons, or delivery service as she and Roy, her husband of nearly four decades, and several of her twelve siblings had. As the years at NC State passed, though, another path to success began to coalesce outside her accounting classes as Rapsody worked on rhymes in a hip-hop collective called Kooley High. Her lyricism stood out in the group and caught the ear of 9th Wonder, who at the time was parting ways with Little Brother to start his own label in Raleigh. After graduation, she decided to stay in town, signing with Jamla.

Knowing Rapsody was serious about music and unfulfilled by the prospect of a career in the finance industry’s white-collar assembly lines, her mother stepped in to ease the way. “I didn’t want Marlanna living here and there,” Margaret Evans said recently. “At first, we went and looked for apartments, and then I decided, ‘Let’s buy a house. Let’s make an investment.’ I just put myself on the back burner.”

“It’s heartbreaking,” Rapsody says, later that day, as we drive around the corner to the home of her grandparents Laila and Nathaniel Ray, affectionately known as “Nay Ray.” “I tell her all the time, ‘Quit your job,’ because she loves interior decorating, which is art. She loves to cook and make cakes, which is art. I tell her, ‘Won’t you just do somethin’ [you love]? Don’t worry about the money.’”

But Evans, a baby boomer, refused then—as she does now—to take the risk. She decided the condo she purchased using some of the equity from her own home would offer Rapsody the stability she needed in the short and long term, another of her parents’ many sacrifices that still makes Rapsody marvel. It’s not unlike the sacrifices Simone’s, Flack’s, and Williams’s parents made for their daughters to take the classical piano lessons that would produce musicians who transliterated the blues and gospel they heard every day with the choral patterns of European masters they committed to memory.

In addition to her parents, Laila and Nay Ray; a tribe of maternal aunts, especially the eldest, Climeradell (“Aunt Dell”); and her cousins, many raised like sisters, have buoyed Rapsody at every step. She recalls countless afternoons and weekends spent listening to Nay Ray regale her with stories about his stepmother as he left fieldwork to open his own business, then retired to nurture a front-porch garden of cucumbers and write down his stories for posterity. (His birth mother had died when he was very young; he’d never seen a picture of her, which made his commitment to his family all the more fervent.) Unlike pensive and reticent Laila, Nay Ray—whose business, Ray’s Place, was not only a juke joint but an after-work hangout for black folk, mostly men, to pal around, play cards and chess, drink, and unwind—liked to effuse about his experiences before he became a Witness, liked to talk about how he saw Snow Hill evolve, slowly, with the nation’s cultural tides.

“He wrote down everything,” Rapsody says, as we take the short ride to Nay Ray and Laila’s home, where her mother’s brother Alfonso (a.k.a. “Fon”), an amateur guitarist, now lives. “He would have a drawer and suitcases full of just stories, of letters. He might pick a day where he would write about something in the Bible or he would write about his grandmother and tell a little story of him growing up.” Before Nay Ray passed away in 2015, six years after his wife, Rapsody’s cousin—called “Aunt” Clementine because Nay Ray and Mama Laila raised her as one of their own— collated his musings into a book, a keepsake the family will pass on to future generations.

Oftentimes, Rapsody and her siblings also spent time a few blocks away from her grandparents’ home, where her Aunt Dell’s dining room table and living room were havens for finishing homework. And when Rapsody first started recording in Raleigh, Aunt Dell’s youngest, Katchia, regularly sent one-hundred-dollar checks to help her tie up loose ends.

In fact, when she and Mark returned from Grammy night, her parents, aunts, and many of her cousins threw her a party to celebrate what was already a win for their family—and Snow Hill.

“That’s a lot of black women,” she says. “That’s the strength and the beauty of black women. Even growing up, I found out the stories my aunts used to keep from me, what was going on in their lives, and I think, ‘Y’all are so strong.’ . . . You have to keep those secrets. You have to find a way to exist in this world, around all the heartache and all the strife. Go home and carry on and go to sleep and get up and do it the next day. That’s just something about black women that I appreciate and always look up to is their resilience through all their adversity. That’s what I always gravitated to, you know, your Ninas and your Lauryns, who always showed that.”

These are women who decided to create boundaries in an industry ruled by men, often at the risk of being dismissed as “difficult” or “crazy” when they chose family or respite over a show. Yet Rapsody takes comfort in their examples of artistic integrity. Contrary to the stereotype of a self-centered star, Rapsody is punctual and insists on honoring her commitments—values she owes to her rearing as a Witness—in a meteoric year that’s had her touring the world promoting Laila’s Wisdom, which interrogates conceptions of beauty beyond the braggadocio about feminine wiles and sexual prowess that dominate the airwaves. As with her debut album, The Idea of Beautiful (2012), and the EP Beauty and the Beast (2014), Laila’s Wisdom ponders the consequences of exploitation for profit and situates joy in self-possession, sifting wisdom from women from her grandmother’s generation, including the late Maya Angelou, who spent much of her latter years at her Winston-Salem estate. Take this verse and vamp from the Grammy-nominated “Sassy,” which contemporizes lines from Angelou’s blues poem “Still I Rise” over a retro 808-heavy beat:

In a league of my ownWatch what you say

You don’t know who you among

Speak a little truth (ahh)

Here come the stones

Throw me a few, look, I got good bones

Diamonds ’tween my knees

Oil wells in my thighs

Does my sassiness upset you?

Oh, you mad that I survived?

On the way up

But what is it about North Carolina’s towns—their quietude and mystery—that tuned the ears and cultivated the songcraft of these truth-tellers?

It’s the week after July Fourth, and Rapsody has taken a break from the road to come home and recalibrate. While her family doesn’t celebrate holidays, they find as many occasions as they can, especially in summer, to enjoy fellowship over food and music. Rapsody has brought mementos, so we decide to ride to Aunt Dell’s home to share the bracelet she’s had made. Stalks of tobacco line the highway as Roberta Flack coos in the background. Her 1977 masterpiece Blue Lights in the Basement is our soundtrack as we ride around town visiting various family members—like thumbing through a virtual photo album of the streets Rapsody and her brother Mark traversed on their bikes.

And as for loving again

Some day somebody might need me

But where would it lead me?

I’d just be rising to fall

After you, what am I gonna do?

You took a part of me

As you were passing through

After you, what am I gonna find?

The me you left behind

As you were passing through

“I might have to sample that,” Rapsody declares at one point, breaking a long silence as Flack’s four-minute deep cut “After You” plays. She gazes into a field, where tobacco leaves loll like seaweed into one another and stalks of corn, bronzed a bit by the sun, shimmer in the heat. She shifts her weight, turns to me, and smiles, not hinting at any human beloved who’s inspiring her in the moment, eager to share instead how Snow Hill’s stillness frees her to bask in the awe of nature and the cosmos that imbues her art with deepened awareness.

“This is home. This is peace. One of the things I love to do every night is that I get out of the car first and look at the sky. You got these cities, you know, and you can’t see it. . . . We don’t ever take the time to sit back and look at what God made. In the country, it’s quiet, and you don’t have a lot of city lights, so when it’s nighttime, you can hear the crickets, and it’s dark, the stars are really bright. Those are the things I take notice of, and maybe that translates into my writing, or even how I study people. I am quiet and shy, but a lot of times it’s ’cause I’m listenin’ and takin’ a lot in, so I just pick up on the small things. Those are the small things I think that people miss sometimes, and when you remind them of it, it’s, like, ‘Oh, wow! Look.’”

Yet, in this moment of wonder, Rapsody—like the women who raised her—is loath to idealize Snow Hill or her childhood there. She sees it instead as a palimpsest of the sacred and secular worlds she’s occupied, then and now. While the women in her family were devout Witnesses, the men in her life gave her a glimpse of life outside the Kingdom Hall and that oft-maligned community. Her father, who is not a Witness but respects his wife’s faith, encouraged his children to appreciate art as well. “I had this balance. I had this strong foundation, and this spirituality that was taught to me, but at the same time, I had this freedom to see the world and kinda be in it, and my mom always said, ‘You have to live your life for you. You know, I can give you the tools, and you know what’s right from wrong, but at some point, it’s up to you to decide how you wanna live it. The choice whether you want to continue to be a Witness or not is up to you.’”

Likewise, Nay Ray taught her to own all of her choices, even the missteps, as he did after converting. And her father and grandfather encouraged her to emote as she saw fit, not mincing words yet still talking to others respectfully, without condescension or apology.

“When you’re doing music, I think you have to be honest. It was tough. I wasn’t concerned about the world hearing it, but it was more so my parents. I didn’t want to disrespect them in that way, or I didn’t want to disappoint them, either. ‘You know that language isn’t great language,’ but at the same time, those words”—curse words her mother eschewed but that her father would occasionally utter— “evoke emotions sometimes that are needed. One word I don’t say is ‘goddamn,’ but when Nina Simone says ‘Mississippi goddam!’, it needed to be said in that way to express that emotion. That’s what it was for me, taking these words to evoke how I feel. ‘Shit! Fuck!’ I’ll try to write around them, but it don’t feel the same. You can’t feel the sincerity, or the urgency, or the pain, or the grief, or the anger, unless you put in a curse word.”

She’s also part of a movement of younger artists determined to unseat the stain and shame of a word—“nigga”—that even her dad abhors. “I get it. I understand, and I’m empathetic because of what it means to that history and how it was used,” she says, “but if we give power to it, then that’s what it is. We have the opportunity to make it what it is. We can’t let them have the final say on what that word means.” She refers to Kendrick Lamar’s etymological monologue on To Pimp a Butterfly about the word negus, a title for royalty in Ethiopia and Eritrea as recently as the 1970s, with roots in a Semitic word that means “to reign.” “They took that word that meant ‘king’ and ‘black,’ and used it to [shame us], but we’re going to use it only amongst us. ‘You’re my nigga. You’re my brother. You’re my king. You’re my homie. You’re my friend.’”

Like a perfectly timed long shot in Charles Burnett’s film Killer of Sheep, we ride past Ray’s Place. Rapsody’s uncle Charles runs it now. Men old enough to be our fathers and young enough to be our sons wave and tip their snapbacks. We wave back, then turn two blocks before pulling into Aunt Dell’s driveway. Rapsody laughs, recalling how Nay Ray said “nigga” all the time.

Once inside, Aunt Dell, the fourth of Nay Ray and Laila’s thirteen children and their oldest daughter, reflects upon the paradoxes she observed in the years her dad was a sharecropper. He worked hard all week in the field, she says, where he struggled with being treated “like a child,” so he spent all weekend away from home drinking heavily. Long before he became a Witness, though, she says, he got sober, opening Ray’s Place as a convenience store that eventually became what it is today. Throughout his battle with alcohol, Aunt Dell underscores, “he always made sure that the family had food. That’s one thing I got to tell you about my dad. His family did not go hungry. All those young’uns did not go hungry.” In fact, he provided food from each year’s harvest to the single mothers on their street, who didn’t help her family glean the corn, peas, and other garden crops. His generosity confounded her as a child, she says, “but now I understand. We were being taught what the Bible said, ‘Love your neighbor.’”

Rapsody, seated on the floor nearby, nods and smiles at the woman she sees as a second mother. Aunt Dell beams back, noting her initial surprise that her niece would choose a career that would thrust her into the limelight. “Marlanna was quieter than any of the other children. She would kind of play by herself. She didn’t care if she had a partner to play with or not. . . . Marlanna was a child that you would never see head for any kind of trouble. She was a child that would sit back alone and observe. You would think that she was playing with what she was playing, but her hands was on it, but her eyes was over there, observing. . . . Isn’t that something that you bloom in a direction that you don’t think a person would go?”

Rapsody chimes in that she learned how to listen and lead with quiet confidence from Laila and her daughters, especially Aunt Dell, who worked for years at Maury Correctional Institution and always addressed the men at the prison with the honorific “Mr.” and their last names. “I let them know that they were important to me. . . . You’re somebody. You’re somebody’s child. You’re somebody’s father. . . . Once you gain their respect and let them know you’re just as human as I am on the outside, you’re just caged in for now, but let them remove the cage, and see what kind of person they are. . . . You can be anything you wanna be, but you gotta respect self, and then I can respect you.”

That’s the same ethic Rapsody encodes in songs like the title track from her 2016 EP Crown and “Pay Up” from Laila’s Wisdom. In that album’s ambitious coda, “Jesus Coming,” she interweaves four disparate narratives of untimely death as a result of gun violence so seamlessly that by the time the pastiche washes over you—the perspective moving from a young person at a party to a mom and daughter caught in gang crossfire to a soldier dying in battle on foreign soil—you’re weeping.

Now, a teary twinkle of joy fills these blues women’s eyes as Aunt Dell shakes her head in bemused disbelief, realizing she’s reached more than Maury’s inmates, having inspired her once-shy niece’s bold clarion calls to the world.

Summer has faded fast in the couple of months since Rapsody and I rode with Nina and Roberta on the back roads that will always be a safe place for her to get still, reboot, hear the country muses whispering in the wind. The nation’s Twitter feeds have been flooded with news of adult film star Stormy Daniels’s tell-all about her alleged one-night stand with the president, an imminent prison sentencing for “America’s Dad” Bill Cosby, and Instagrammed fights between Cardi B and Nicki Minaj. Hurricane Florence soon will flood the eastern coast of her home state but spare her Snow Hill kin and only cause a brief loss of power. The fiercely private Queen of Soul is dead, too.

America’s got the blues, so naturally, I call Rapsody to see what music has been inspired by her visit home and current events. She confirms that she’s been in the lab, trying to find words that at once offer a stark look in the mirror and provide a balm—as she’s always done. On this evening, she’s getting glammed to perform in Chicago, where she’s closing out another festival season. We discuss her spot on Black Girls Rock!, recorded days earlier in Newark’s New Jersey Performing Arts Center. “I think you’ll like it,” she says in the unassuming way she was raised to share her light.

I decide to tune in. Producers have included her as the penultimate act, aptly, in the show celebrating black women’s innovations in various art forms. Honorees include #MeToo movement founder Tarana Burke; burgeoning TV/film writer and producer Lena Waithe; supermodel Naomi Campbell; ballet pioneer Judith Jamison; global music icon Janet Jackson; and two other musical queens, recently departed Aretha Franklin and her living heir, Mary J. Blige. The host is Queen Latifah, and by way of introduction she reminds anyone who doesn’t know that the next performer was named one of the twenty best female rappers of all time by XXL for using her elevated wordplay to illuminate the world around her. “From Snow Hill, North Cacka-lacka, please welcome RAPSODYYYY!”

Whereas others have come forward with elaborate bands, dancers, and glitzy backdrops, Rapsody takes a clean, understated approach—it’s only her, the spotlight, and the mic commanding the crowd’s attention tonight. She’s wearing a red-trimmed black pantsuit and red blazer. Stiletto pumps, a gold choker and bracelet, akin to the one she gifted Dell and other aunts, and glints of partial diamond grills around front incisors make the outfit pop, her hair in short braids reminiscent of Cleopatra (or Da Brat, depending upon your crew). She eases into her poem “A Penny for Your Thoughts”:

I am Nina and Roberta

The one that you love, but ain’t heard of, got myHead up like Pac after attempted murder

They fail to kill us, we still here

Woke up singing Shirley Murdock

As we lay these edges down

Brown women, we so perfect,

Went from in the field, but they still

Trying to crop us out the picture

But we all know who got the juice

My sisters imitating us in all they Hollywood pictures

Watching from home, you can see heads bobbing and nodding in the crowd as “Go ’head!” echoes in the hall. She takes their cue to go deeper.

I seen ya, so I exalted our realness

That good love you feeling

That blackness, you can’t buy with a million

We are one in a million

Motherly, protective, classy, introspective

God-fearing, cutthroat, the one they all

Respect it’s queen in me, huh, I got that

Gene in me from all the queens I seen

Emitting that glow, you know,

My mama, yo’ mama, homegirls, sistas

Phylicias, Arethas, Cicelys, Anitas, they knowSuperwoman, worker bee, career women

That came home, cooked, and cleaned

It takes a strong woman to balance those thingsWalking the fine line of life with no balance beamsAll the while carrying child,

We are the strongest human beings, queens.

“YAAAS!!” reverberates as applause erupts. I imagine Rapsody thinking of the queens in her life—Mama Laila, Margaret, Dell, Clementine and other aunts, her sisters, and all her sister-cousins. I imagine, too, her galvanizing the fortitude of Nay Ray and Roy, the men who loved these queens and her, their ambassador to the world, as she raises her voice and tempo.

If you ever wondered, what a Wonder-woman bringsTo the table, Solange said take a seat,

Where thrones repeat, repeat, repeat

That’s how royalty eats together

Sisterhood, we are better for the village

On top of Mount Zion, like Ms. Hill is, shine.

Black girls rock, shake, and rhyme.

Penny for a thought, but we gave them dimes

’Cause all my sisters fine.

Arms wave as some audience members stand and undulate, steadied by her flow. She pauses as the camera pans to the honorees, leading the groundswell to its peak.

Fine to the bone, royalty upon the throne,

We are queens.

With her performance, Rapsody encapsulates the spirit of sisterhood that has permeated everything that came before, and the love overflows. Now, the one who had given love so freely to her homie Kendrick Lamar months earlier is met with an outpouring she won’t soon forget. The entire audience leaps to their feet, members of a #BlackGirlMagic Church that her hip-hop blues has built, capping a year that began with her dropping a game-shifting album and traveling the world to gather a critical mass of hip-hop fans—who’ve been waiting. As she’s done time and again, in honoring others, her words bring into relief what legendary black women—through ups and downs, heartaches and traumas—consistently show America: how to be unapologetic in speaking powerful, necessary truths, unashamed of one’s home, unwilling to compromise one’s values for fame.

“My message, I don’t think, will ever change, like, it will always be the same,” she says. “I’m gonna talk about what’s happening in the world, what’s happening in my life. That’s what it’s gonna be. What’ll change is sonically, what’s the backdrop, what’s the sound of that, you know. . . . You can evolve your sound. You have a lane, and you can grow in it, but that doesn’t mean you have to skip over and go to somebody else’s lane. I ain’t doing that.”

If history is the best forecast for what’s to come from Rapsody, she’ll rise to this occasion—Snow Hill at her back—and deliver exactly what we need in these uncertain, precarious times.

“Chrome (Like Ooh)” by Rapsody—produced by 9th Wonder—is included on the North Carolina Music Issue Sampler.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.