Take a Day and Walk Around

By Savanna Bader

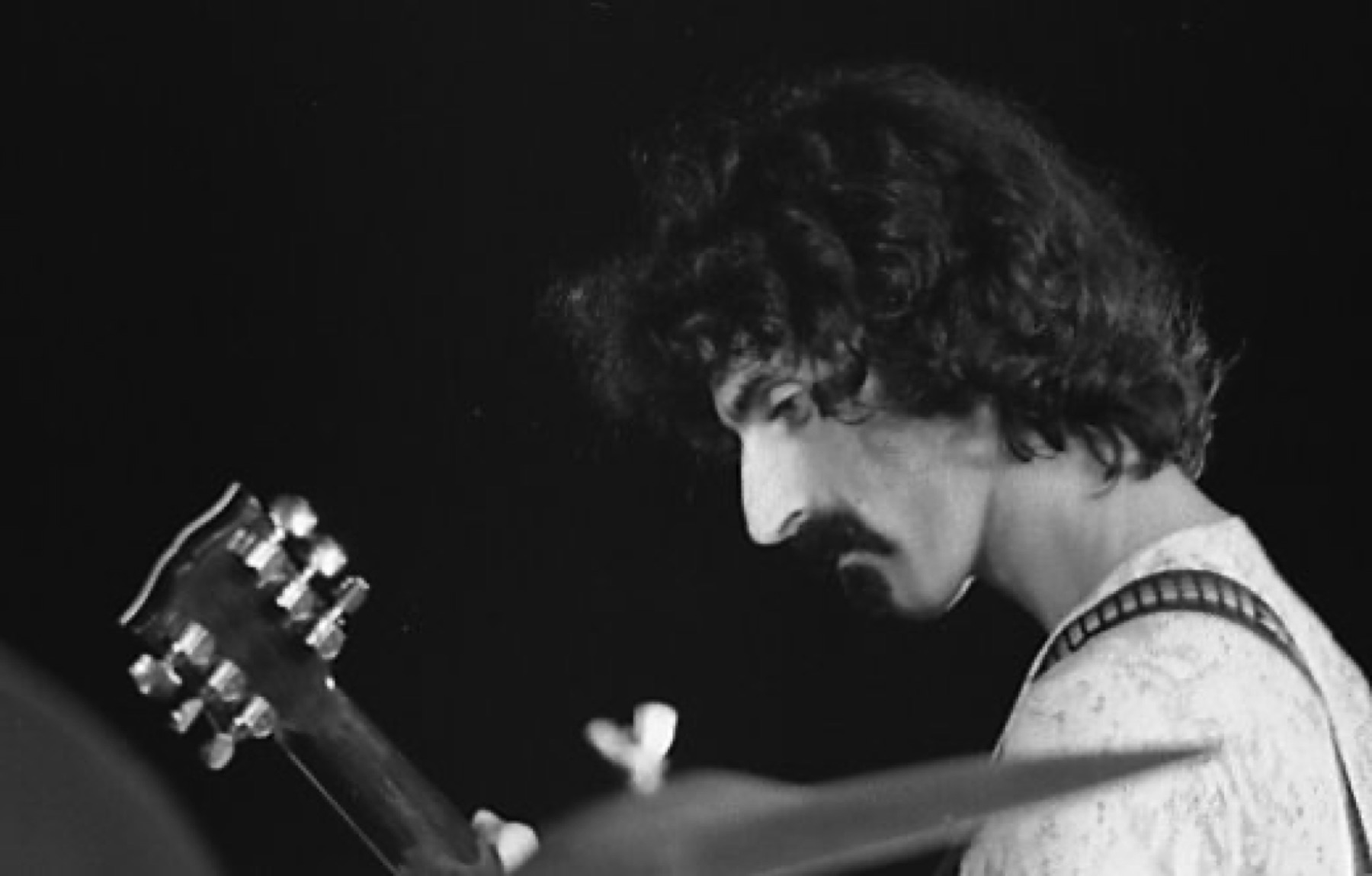

Mothers of invention, Theatre de Clichy, Paris, 1970-1972. Photo by Jean-Luc, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

On paper, the fact that Frank Zappa, a musician heavily influenced by classical arrangements, reggae, doo-wop, and jazz, would in turn influence Czechoslovakia’s transition from communist rule, seems outlandish. For one, Zappa was born in Baltimore to Italian American parents and grew up in Maryland and Florida during the ’40s before finally settling in California. In the late ’80s Zappa was remastering a majority of his discography while Czechoslovakia was under strict Soviet control, and music, the samizdat (banned literature), and other forms of art were produced and circulated under secrecy for fear of imprisonment. During the 1989 Velvet Revolution, Czechoslovakia was on its way to becoming democratic, and, in the following year, Zappa would be diagnosed with terminal cancer.

Yet in 1991, just three years after the transfer of power, Zappa performed a show in Prague for thousands of dedicated fans. How Zappa even landed in Prague is a mystery considering how anything of Western influence was outlawed as contraband. He likely existed in third-market records before he was ever physically in the city. As he stood in front of the audience, he seemed shell-shocked as his words were relayed in Czech. His body frail, he looked out onto an eager crowd and uttered these words: “Please try and keep your country unique.” The translator repeated his statement, the word “unikátní” hanging in the air, and then Zappa began the self-described grueling process of tuning his guitar.

Beginning in the 1960s, Zappa fronted the Mothers of Invention, later stylized simply as the Mothers, which was an experimental rock band formed in Southern California with guitars, drums, pianos, keyboards, flutes, clarinets, trombones, saxophones, flugelhorn, and countless other instruments. Their song “Plastic People” inspired an entire generation, but more interestingly, the song is a well-documented inspiration to the Plastic People of the Universe, a Czech rock band active in the underground music scene during the communist regime. Initially the Plastic People of the Universe were a government-appointed cover band hired to play acceptable covers of Western music, but their tendency to perform music that went against the “official” culture resulted in their performing license being revoked. Without the necessary license required for any type of performing, not just music, they continued to play their original songs as well as covers of Western rock bands like The Velvet Underground, the Fugs, and the Mothers at underground concerts.

In the song “Plastic People,” Zappa sings, “Take a day and walk around / Watch the Nazis run your town / Then go home and check yourself / You think we’re singing ’bout someone else,” with the vigor of an anti-establishment American. He was an atheist, pro-capitalism, anti-Communism, anti-censorship, anti-drugs, pro-tobacco, and the perfect figure for critical Americans to worship. He never dreamt this line would resonate with an Eastern European country under strict government control; he was ambitious—his extensive discography proves this—but his ambitions were limited to the U.S. His Western fans appear randomly in YouTube comment sections and online forums: “60s era Mothers of Invention kept me sane throughout high school. RIP Uncle Frank!”, Owen Adams Music says. From eight years ago: “A theme song for today's global society........” says frigadigit. From last year: “Can you imagine what Frank would have made of the Donald.”

“But Czech and Slovak listeners knew that it was also the case of our country—so they easily adapted all these hidden messages to their own situation,” Petr Doružka, journalist and author of Šuplík plný Zappy, explained. This thin book, also known as A Drawer Full of Zappa, was the only Zappa knowledge, personal and artistic, available to Czechoslovakia when it was published in 1984. It contained random snippets of factoids and was exclusive to “the Club of Friends of Young Music,” a de facto paywall created by the club to limit Czech culture’s exposure to Zappa and the subsequent risk of having his music confiscated. The Club of Friends of Young Music was both successful and unsuccessful; Zappa’s influence over the Czech underground scene prior to 1989 is undeniable. Police would shout “turn off that Zappa music” at young people listening to rock music and he was heralded as “one of the gods” of the Czech underground music scene by President Havel. In early 1990, Havel would name Zappa “Special Ambassador to the West on Trade, Culture and Tourism.” For a brief moment before his death, Zappa’s aspirations turned global; he planned to facilitate trade between former Soviet and Western countries.

During his 1991 performance in Prague, Zappa played what he called “reggae improvisation in the key of A.” His backing band began a simple reggae beat while Zappa wailed on his guitar, the sound fuzzy but sharp with skill. He played with emotion, with sincerity. Zappa dabbled in too many genres to count, but he frequently returned to the Jamaica-born style for his improvisations because he found it liberating. Interestingly, Zappa admitted that he enjoyed playing reggae more than listening to it: “Reggae is a ventilated rhythm. If you’re going to play a solo with a lot of notes in it and your rhythm accompaniment has a lot of notes in it, then it neutralizes it. I find it more intriguing to play to a reggae background with jagged pulses and big holes in it—there's blank space.” This same analytical approach can be seen in Zappa’s classical albums as well as his comedy tracks.

Midway through his career, Zappa declared that what he did, as a musician, movie director, producer, or artist was “designed for people who like it, not for people who don’t.” Standing on the Sports Hall stage and watching him focus on his guitar, the sounds it made, how it complimented the reggae riffs coming from his band, it’s not hard to understand what he meant by that. Zappa released more than sixty albums during his lifetime, their genres ranging from the progressive rock of the Mothers, to satire and instrumental jazz. He was about freedom of speech and art and expression, but more importantly, his work stood for uniqueness.

Take a day and walk around Prague and you’ll hear snippets of modern r&b and top 100s. No Zappa. Unlike Lithuania, there are no large monuments for Zappa, and in 2021, you’re more likely to hear Doja Cat than anything by Zappa playing in the streets.

But his influence is there. Of course it is—Zappa fans will never let you forget it even if the generational difference grows bigger and bigger. Forty minutes outside of Prague is a place called “Caffé Zappa Bar.” In 2016 the Czech National Symphonic Orchestra performed “Musics by Frank Zappa/Orchestra En Regalia.” His face might not be plastered onto building walls, but he’s still there, resonating in Prague’s history.