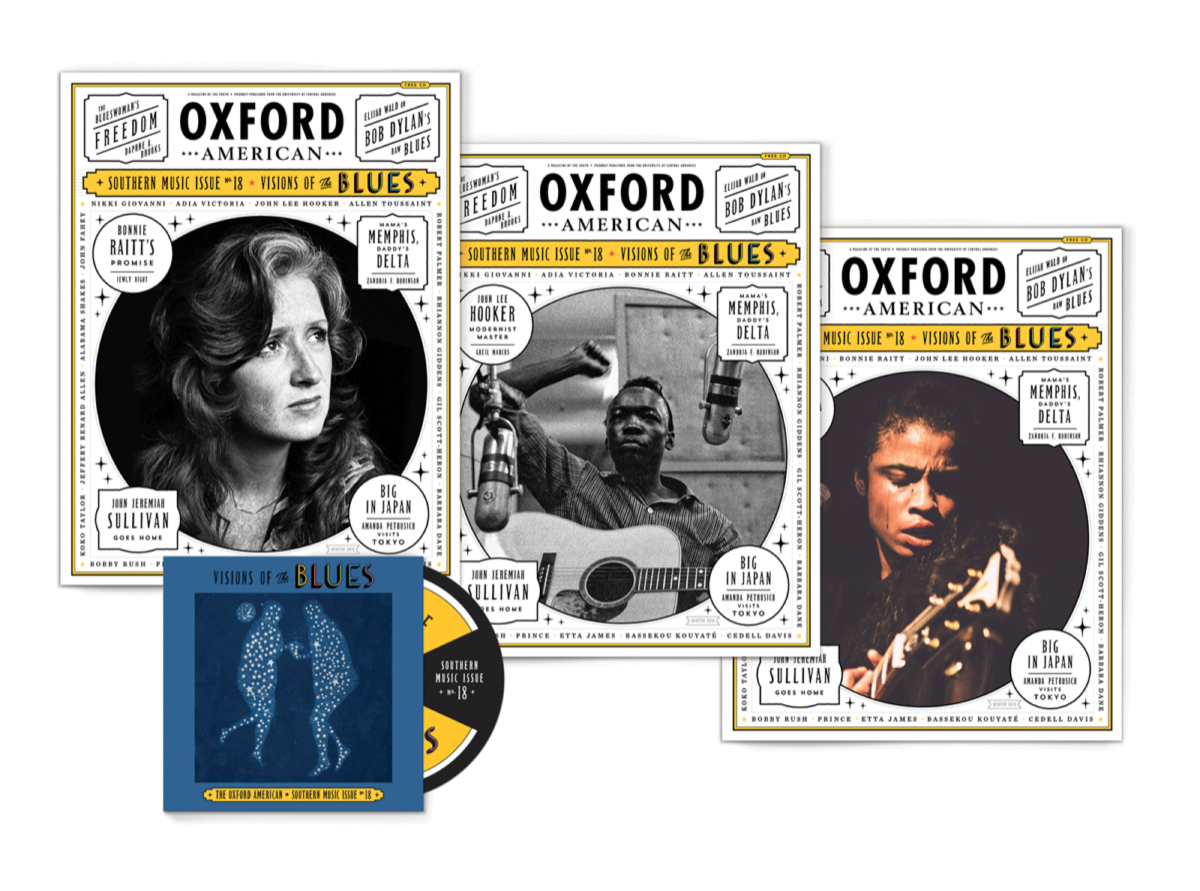

Visions of the Blues

By Oxford American

“At Messengers Pool Hall, Clarksdale, MS” (2011), by Magdalena Solé

Notes on the songs from our 18th Southern Music Issue CD: Visions of the Blues

For nearly three decades, beginning in 1950, a stream of world-class performers of jazz, folk, blues, and what we would now call roots music passed through Lenox, a small town in the Berkshires of western Massachusetts. Louis Armstrong, Ornette Coleman, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Dave Brubeck, Odetta, Muddy Waters, Bob Marley, Bonnie Raitt, Taj Mahal. They came to visit the Music Inn, a country estate that Philip and Stephanie Barber bought and transformed into a cultural gathering place where musicians, many of them African American, were invited to converse about their craft and to perform together in an intimate, informal setting. The intention was “to explore the beginnings of jazz, where it came from,” as Stephanie told writer Seth Rogovoy in 1995. “Everybody was always arguing about that. Did it come from Africa, did it start in the South, did it come from Africa to the South?” The sessions eventually spawned the Lenox School of Jazz, short-lived but seminal, and in the sixties and seventies the Music Inn changed hands and morphed into an outdoor performance venue. But its early intellectualism—a curiosity about the origins of not only jazz but traditional American music more broadly—is what attracted the musicians and scholars that put it on the map. “We would invite people from different parts of the world to play with each other,” Barber remembered, “and the next morning a panel of experts would discuss what happened the night before.”

In 1951, when the place was still somewhat of a secret, John Lee Hooker dropped by. The photographer Clemens Kalischer, who owned a gallery in town, made two pictures of him. One is candid—Hooker smiling and riding shotgun in musicologist Marshall Stearns’s convertible. The other shows him seated at the “Folk and Jazz Roundtable,” in a smart suit and flashy tie. In this more formal portrait, Hooker sits before a coffee cup with his elbows on the table, his right hand gripping his forehead. His gaze is fixed just right of the vantage point. Behind and above him, a tall chalkboard looms, featuring a carefully drawn diagram titled THE BLUES (each word double underlined) charting the influences and offshoots of the genre. Arrows point down from grandparent categories like MARCH, HYMN, and RING SHOUT – CRIES / WORKSONG to the more specific RAGTIME, SPIRITUALS, DANCE-GAMES, and JUG BANDS, eventually culminating in tiers of distinct genres: EARLY BLUES, GOSPELS, N.O. JAZZ, HILL BILLY, and THE BLUES. A few uncertain timestamps—1820?—are scattered around. At the bottom of the board (the end of the road) arrows lead separately from N.O. JAZZ and THE BLUES to the words MAIN STREAM (1920). Below that is Hooker, head in hand.A natural reaction is to commiserate with Hooker—gosh, that looks exhausting—to project onto him one’s own annoyance with the unceasing fetishizing of blues music, a practice that has continued in step with the progression of the genre itself. It is startling to think that when Hooker visited the Music Inn, the “rediscovery” of Bukka White, Son House, Mississippi John Hurt, and Skip James that fueled the country-blues revival of the sixties was still more than a decade away. But spend time looking at Kalischer’s photograph—one cannot help but do so—and the image assumes a calming quality. How comforting to know that the murkiness of blues provenance confounded us sixty-five years ago, as today. Hooker cared deeply about those origins, and he stretched and bent them in his own manner (see: Greil Marcus on Hooker’s “John Henry,” track 11).

The blues cannot be contained. Not in one song, not in one person; nor in one hundred. Its beginnings are lost, its history too primeval, its diffusion into our music and culture too wide-ranging. The blues is among the South’s greatest exports, and its continued evolution at the hands of artists like Otis Taylor, Rhiannon Giddens, Alabama Shakes, and Adia Victoria is as rich and unpredictable as ever.

As we conceived of this issue, we sought a model for our task. (Metaphor, after all, is a hallmark of great blues.) The natural impulse behind this work, music writing—blues music writing, no less—points to the image of the lantern: illuminator, bringing light to darkened places. But a more appropriate one here is the prism: refractor, dispersing pure light to reveal the color spectrum.

The blue light was my blues, and the red light was my mind. Sound and color. We listen, we dream, we imagine. We receive these visions.

The train rolls on.

—Maxwell George

1 “ROCKS IN MY BED”

Allen Toussaint with Rhiannon Giddens

“Rocks in My Bed” is part of a sad, unexpected envoi for Allen Toussaint, who died at age seventy-seven in Madrid in November 2015, just weeks after the album on which the song appears, American Tunes, was completed. The legendary composer, arranger, and performer was New Orleans royalty and understated elegance personified, a worthy heir to the song’s composer, Duke Ellington (with help from Billy Strayhorn). Rhiannon Giddens’s gently swinging vocal manages to be both precise and soulful, and it’s easy to imagine this version sliding seamlessly into the 1941 stage musical revue, Jump for Joy, for which it was originally written. Ivie Anderson and Ella Fitzgerald recorded memorable renditions, but Joe Turner always said the song was written for him. The aim of that all-black revue, which opened in Los Angeles but failed to transfer to Broadway—at least partly because the attack on Pearl Harbor changed the mood of the country—was, Ellington said, “to give an American audience entertainment without compromising the dignity of the Negro people.” An additional ironic echo of the song’s history is that Giddens’s own planned Broadway debut in the revived 1921 revue Shuffle Along was halted when that show closed. However, as Gayle Wald writes in “Past Is Present,” Giddens hasn’t let that disappointment slow her career; a new album, which synthesizes “polished modernity and respect for tradition,” comes out in 2017.

In the magazine: Gayle Wald on Rhiannon Giddens.

2 “YES, IT’S GOOD FOR YOU”

Koko Taylor

Until her death in 2009, Grammy-winning Koko Taylor was among the biggest stars of the Chicago blues circuit, claiming the mantle of “Queen of the Blues.” She’d come a long way from Memphis. She was born in 1928 on a sharecropper’s cotton farm outside of the city, where she grew up admiring Ma Rainey and other blueswomen until she moved north in 1952 with nothing but “thirty-five cents and a box of Ritz Crackers,” as she liked to say. Once she arrived in Chicago, Taylor cleaned houses on the North Side—and went out to clubs at night, occasionally sitting in with Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. She recorded her first record in Willie Dixon’s basement, and Dixon introduced her to Leonard Chess in 1965. “Yes, It’s Good for You” is from Taylor’s debut Chess album, where her full-throated voice is on powerful display. In a 2002 interview, Taylor recounted her early experience of developing this signature sound: “When Willie Dixon first heard me sing, he said, ‘My God, I never heard a woman sing the blues like you sing the blues.’. . . What you hear comin’ out of my mouth is a God-given talent. I could sing the blues in January and still sweat. If you ain’t sweat, you ain’t done sang the blues.”

3 “NEW YORK IS KILLING ME”

Gil Scott-Heron

A poet and novelist before turning to music, Gil Scott-Heron became a primary influence on hip-hop and remains most famous for his 1970 jazz-funk and spoken-word anthem, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.” But he mostly rejected his legacy as a harbinger of rap. At heart, Scott-Heron was a soul man, a jazzman, a bluesman. On his final album, 2010’s I’m New Here, he interpreted Robert Johnson’s “Me and the Devil” as a synth-laden romp, and he composed the (somewhat) straightforward blues “New York Is Killing Me,” partially inspired by John Lee Hooker’s “Jackson, Tennessee.” (He described that song as “too fucking dark.”) Scott-Heron grew up in Lincoln, Tennessee, and said his earliest music memories were “the blues and playing in church. We weren’t that far from Memphis and that’s the music they were playing there.” After Scott-Heron died at sixty-two in 2011, Kanye West performed at his memorial service and Chuck D called him “the manifestation of the modern word.” But Scott-Heron would have preferred to be remembered by the label he created for himself: “bluesologist.”

4 “MEMPHIS MAIL”

Scott Dunbar

The son of a former slave, Scott Dunbar (1904–1994) was born, raised, and spent most of his life around Lake Mary, a small oxbow off the river in the southwest corner of Mississippi, where he worked as a fishing guide and musician. William Ferris, who recorded him on a number of occasions, noted that Dunbar, in addition to being a “songster who composed and sang a wide range of blues,” was “a gifted storyteller whose tales vividly described the worlds of black religion, white fishermen, and the military at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. He used his wit to survive in these worlds, and his stories are filled with both humor and pathos.” Dunbar’s version of “Memphis Mail,” a traditional he’d picked up from local elders and refashioned into a signature tune, is beautiful and joyful. In the liner notes to Dunbar’s only full-length album, From Lake Mary (released on the obscure label Ahura Mazda in 1970), the artist is quoted on his musical philosophy: “Well, I’ll tell you—if it feels good to the people it feels twice as good to me.” This version comes from a box set of Ferris’s Mississippi field recordings, to be released by Dust-to-Digital in 2017.

5 “STUCK IN THE SOUTH”

Adia Victoria

“I don’t know nothin’ ’bout Southern belles,” sings Adia Victoria in “Stuck in the South.” Then she delivers the punch: “But I can tell you something ’bout Southern hell.” Raised in Spartanburg and Campobello, South Carolina, before escaping to New York, then Atlanta, and finally Nashville, Victoria makes us believe the rage-filled words on her debut album, Beyond the Bloodhounds, released in March 2016. Victoria has talked openly about her upbringing as a Seventh-day Adventist living under the poverty line, and the jolting experience of transitioning from church school to a large public school when she was in sixth grade—of not fitting in, of feeling like a freak. But when she moved to Atlanta, Victoria was inspired by the Delta blues. In 2014, she reflected on this discovery in an interview with Oxford American contributor Jewly Hight (for the website Wondering Sound): “The blues spoke to another part of me—the rambling spirit in me, the restless spirit, the Southern in me. I embraced being from the South and being a black woman through the blues. It made me feel more connected to my culture.” Hear the influence on this electric and chilling single, which concludes with a tip of the hat to Robert Johnson, Elmore James, and R. L. Burnside. “I’m going to dust my broom,” she tells us. “Yea, I’m leaving soon.”

On OxfordAmerican.org: a conversation with Adia Victoria.

6 “SEGU BLUE (POYI)”

Bassekou Kouyaté & Ngoni Ba

“Many West Africans, especially in Mali, heard blues on the radio or were exposed to it through Ali Farka Touré; this would certainly have been true in Segu, the center of Bamana culture where Kouyaté grew up. African radio programmers were naturally attracted to blues. They sensed something of themselves in it, likely because, as Kouyaté firmly believes, the Delta blues grew from traditions transported across the Atlantic by Bamana musicians sold as slaves.”

Read an essay on this song by Banning Eyre.

Also: Alex Steyermark and Lavinia Jones Wright profile Bassekou Kouyaté.

7 “DOWN THE DIRT ROAD BLUES”

Charley Patton

In terms of influence, Charley Patton, born in the vicinity of Clarksdale in the Mississippi Delta in 1891, is the greatest artist of the early blues. His understudies included Tommy Johnson, Willie Brown, Son House, Howlin’ Wolf, Robert Johnson, and Roebuck Staples, performers who looked up to the older Patton and who came through Dockery Farms, the plantation near Cleveland where he lived.Then there is the impact of his recordings, made between 1929 and 1934 for Paramount and Vocalion (fifty-two survive). One of Patton’s masterworks is “Down the Dirt Road,” “which, for sheer rhythmic complexity is the most striking performance in the whole of blues,” notes Elijah Wald in Sing Out! magazine. A provocative but not unreasonable assessment. This being the early blues, much about Patton is contested (including the spelling of his first name). In his book Deep Blues, Robert Palmer championed Patton as among the most significant American musicians of the twentieth century, pointing out how, as a singer, he “often seemed to alter the stresses of conventional speech for purely musical ends.” It’s certainly true of this song, and so the lyrics are a matter of interpretation. Most hear the first stanza this way:

I’m going away to a world unknown

I’m going away to a world unknown

I’m worried now, but I won’t be worried long.

In Patton’s confident, enigmatic growl we encounter some central juxtapositions of the genre: trouble with relief; searching yet knowing; approaching death and existing beyond it.

8 “WILD WOMEN DON’T HAVE THE BLUES”

Ida Cox with Coleman Hawkins Quintet

In “See My Face from the Other Side,” a feature in this issue, Daphne A. Brooks writes of “the classic blueswomen’s craze” launched by Mamie Smith in 1920—“an unprecedented era in which black women’s voices occupied the center of mass cultural life.” Ida Cox—who was born in Toccoa, Georgia, in the late nineteenth century; who as a teenager ran away from home to join a minstrel revue; who went on to headline as a vaudeville star; and who was promoted by Paramount as the “Uncrowned Queen of the Blues”—fits squarely into this era, along with her better-known contemporaries Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. The delightfully brash “Wild Women Don’t Have the Blues,” first recorded in 1924, is Cox’s most enduring hit, covered by artists like Cyndi Lauper, Barbara Dane, and Francine Reed. More than ninety years later, the feminist message holds up: “I’ve got a disposition and a way of my own / When my man starts kicking I let him find another home.” This version is from her final album, Blues for Rampart Street, recorded when Cox came out of retirement in 1961—by then her singing was limited to Sunday mornings at the Patton Street Church of God in Knoxville. Producer Chris Albertson of Riverside Records convinced her to travel from Tennessee to New York and lay down a few tracks at Radio City Music Hall with the great tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins and his supergroup: blues pianist Sammy Price, trumpeter Roy Eldridge, bassist Milt Hinton, and drummer Jo Jones. Cox died in 1967.

9 “TEN MILLION SLAVES”

Otis Taylor

“The folk thing was about civil rights,” according to Otis Taylor. “Folk music is the music of the working class, the music of the folks. Blues is folk music.” Taylor doesn’t remember exactly when he said this, but it’s become such an indelible quote that you can now read it at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture, opened in September 2016, where a picture of the musician is featured on a display titled “The Legacy of the Banjo in America.” Growing up in Denver in the middle of the twentieth century, Taylor began playing banjo in his teens, unaware of its African origins. For his 2008 album Recapturing the Banjo, Taylor enlisted a formidable group of musicians—Guy Davis, Keb’ Mo’, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Corey Harris, and Don Vappie—to create a kind of alternative, Afrocentric popular history of the instrument. (For example, Hart reworks the traditional folk ballad “Deep Blue Sea” as a Mississippi hill country blues.) “Ten Million Slaves” is a Taylor original, which first appeared as an acoustic song on his 2002 album Respect the Dead. It’s a haunting story that traces a line from a historical horror (slavery) to a future one (nuclear apocalypse). As he explains it: “An African-American man sits in a fallout shelter thinking about slaves in the Middle Passage.” This nightmarish quality is heightened by the thumping bass and backing wails of daughter Cassie Taylor and the repeating intertwined acoustic and electric banjo riffs, a hypnotic layering of sound that is Otis Taylor’s signature brand: “Trance Blues Certified.”

10 “BLACK RAT”

Big Mama Thornton with Muddy Waters Blues Band

Big Mama rarely sounded bigger than she does on this cut from a session that Arhoolie Records’ Chris Strachwitz put together in 1966 in San Francisco. (Strachwitz and critic Ralph Gleason pronounced her the “greatest living” blues singer during the blues revival of the 1960s, as Cynthia Shearer recounts in the magazine.) At this point in her career, Willie Mae Thornton’s reputation could hardly have been smaller, her 1953 hit “Hound Dog” eclipsed a decade before by Elvis Presley’s version and her “Ball and Chain” not yet recorded by Janis Joplin. She’s certainly pissed off at somebody and turns Memphis Minnie’s jaunty blues “Black Rat Swing” into a full-throated revenge tragedy, backed by the best blues band of the era. In addition to Muddy’s licks, James Cotton’s harmonica cries in pain, that rat’s tail under a heel.

In the magazine: Cynthia Shearer on Big Mama Thornton.

11 “JOHN HENRY”

John Lee Hooker

“For three minutes, it’s as if Hooker has just woken up from a dream and is trying to remember it. The song as such is nothing but fragments, fragments of fragments. Lay that hammer down is a repeating theme, but as an idea, or simply an image, nothing so strong as the folk meaning of the theme, which is telling John Henry to save his life.”

Read an essay on this song by Greil Marcus.

12 “ONE OF THESE DAYS”

CeDell Davis

Previously unreleased.

In 1982, the New York Times pop music critic Robert Palmer invited his fellow Arkansan CeDell “Big G” Davis to play a two-week engagement at Tramps in Manhattan. “Davis was treated like rediscovered royalty,” David Ramsey writes in “Still Around Here.” While there, he “recorded an album’s worth of songs at Brian Eno’s studio” with trumpet player Gary Gazaway, drummer Sticks Evans, and Palmer playing a clarinet clearly inspired by his many trips to Morocco. Ramsey calls it “Davis at his peak, anchored by a trippy, blithesome fusion.” Those tapes were lost until 2012, when the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane notified Gazaway that they’d found some master reels among the late Palmer’s papers. He got the blessing from Palmer’s daughter, Augusta, to retrieve the tapes, which had to be painstakingly restored. On “One of These Days,” from the still-unreleased New York Sessions, we hear Davis twelve years before he would make his first proper album, Feel Like Doin’ Something Wrong. Today, Davis is ninety years old and still performs and records—his latest album, Even the Devil Gets the Blues, came out in October—though he can no longer play guitar in his singular way, employing idiosyncratic tunings and a butter knife on an upside-down instrument. But here you can find him in top form, plying his ragged—jarring to some—erratic guitar style over a laidback but forceful 12-bar groove. Davis demonstrates what many musicians and fans have recognized: that he is a bluesman like no other, unrepeatable.

In the magazine: David Ramsey on CeDell Davis and Jay Jennings on Robert Palmer.

13 “CHICKEN HEADS”

Bobby Rush

It is unclear how old Bobby Rush is—sources are conflicting and the man himself has claimed various birth years—but he is not young. In the neighborhood of eighty-three, Rush keeps a busy tour schedule, with a decidedly flashy, funky, and fun live show (we hosted him in the Oxford American’s performance space in Little Rock in 2013). The “King of the Chitlin’ Circuit” grew up in Homer, Louisiana, and Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and he took up singing as a child after tuning in to Nashville’s 50,000-watt WLAC. That was where he first heard singers like Muddy Waters and Louis Jordan, whose “Ain’t Nobody Here but Us Chickens” gave Rush the idea for “Chicken Heads.” By now, he has recorded more than three hundred and forty-five songs, and “Chicken Heads”—his first gold record, released in 1971—remains one of his most beloved. Over the years, Rush has cut records for Checker, Galaxy, Rounder, and Malaco (in the magazine, Rashod Ollison pays tribute to this Jackson, Mississippi–based label, which released music that “celebrated an indomitable spirit, encouraging listeners to laugh, not cry; to rise in love, not fall”). Through it all, he has been a world-class entertainer. “When I’m on the stage, it’s not that I’m trying to get the blues across,” he told William Ferris for the 2011 music issue of Southern Cultures. “I’m trying to get Bobby Rush across, and if that gets the blues across, that’s a plus.”

In the magazine: Rashod Ollison on Malaco Records’s raunchy blues.

14 “PICK POOR ROBIN CLEAN”

Geeshie Wiley & Elvie Thomas

“She was born; presumably by now she is dead,” wrote Greil Marcus in “Who Was Geechie Wiley?” an essay published in the Oxford American’s third Southern Music issue in the summer of 1999. “The rest of the story can pretty much be subsumed under, as Robert Crumb once put it, the ‘connection to eternity, or whatever you want to call it.’” How things have changed—and remained the same—in the intervening years. We’ve learned more about the biography of Wiley and her guitar partner, “Elvie” Thomas, but their six recorded songs, cut for Paramount in 1930, are as enigmatic as ever. Daphne A. Brooks places Wiley and Thomas in a long tradition of blueswomen (from Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith to Lauryn Hill and Mary J. Blige) who, in the form of the duet, practice and display a kind of improvisational and collaborative wisdom. In Brooks’s view, “Pick Poor Robin Clean”—which has been “discounted by some as a showbiz trifle”—is the most important song in their repertoire. She writes, “Having each most likely stared the Southern penal system in the face, they made music that pushed beyond blackface parody to embrace a partnership in ludic mischief.” This song is a prime example.

In the magazine: Daphne A. Brooks on Geeshie Wiley & Elvie Thomas.

15 “YOU DON’T KNOW ME”

Barbara Dane

Singer. Songwriter. Guitar player. Nightclub owner. Activist. Of her different identities, “resister” is the one that most resonates with Barbara Dane. She walked picket lines in her hometown of Detroit in the 1940s; played in Cuba after the Revolution, the first U.S. musician to do so; founded Paredon Records, which put out fifty albums of protest music, in 1969. She’s a longtime hero of Bonnie Raitt’s, who has said “there really isn’t anyone that accomplished as much as she did, in terms of breaking barriers and standing up for what she believed in.” Over a long career that is still going strong—in August 2016, she released her first record in fourteen years, and in May 2017, she will turn ninety—Dane has crossed genres of folk, jazz, and blues, performing with Louis Armstrong and recording with Lightnin’ Hopkins. She was the first white woman to be featured in Ebony magazine, under the headline WHITE BLUES SINGER: BLONDE KEEPS BLUES ALIVE. The 1959 article praised her “dusky alto voice,” moaning of “trouble, two-timing men and freedom.” Our favorite introduction to Dane’s music is Barbara Dane Sings the Blues, released by Folkways Records in 1964 (Smithsonian Folkways reissued it forty years later). “You Don’t Know Me” is the first song on the first side. Pair with “You Don’t Know My Mind” by Leadbelly.

16 “MY HEAD IS BALD”

Tail Dragger

Born in Altheimer, Arkansas, in 1940, singer James Yancy Jones grew up enchanted by the blues and moved to Chicago’s West Side in his mid-twenties, where he became an acolyte to Howlin’ Wolf. For years, Jones was allowed to perform during Wolf’s set breaks, eventually earning the moniker “Tail Dragger” (after Wolf’s song of the same name), because he was often late. When the Wolf died in 1976, Dragger took up his torch. “My Head Is Bald” was recommended to us by Bob Koester, founder of the legendary jazz and blues outfit Delmark Records, as a formidable example of Chicago’s enduring blues scene after the heyday of the 1960s. Originally released on guitarist Jimmy Dawkins’s short-lived hometown label, Leric, in 1982, the song features a band comprising the city’s tenured best, including Willie Kent on bass, Eddie Burks on blues harp, and Johnny B. Moore on guitar. “My Head Is Bald” transports the listener to one of the many small clubs on Chicago’s South and West sides—Ma Bea’s, say—where for decades smoky electric blues was played late into the night on weekends. It can still be found in pockets, and Tail Dragger continues to perform today. As he says, “Lowdown blues is all I like . . . All I feel.”

17 “MISS YOU”

Alabama Shakes

“This song is a new model—built on a standard frame, maybe, but showing an understanding of how the blues legacy both enables the expression of chaotic emotions and streamlines them, tuning them up for maximum performance within a structure that demands precision as much as openness.”

Read an essay on this song by Ann Powers.

18 “EPIROTIKO MIROLOGI”

Alexis Zoumbas

Prewar 78 rpm record collector and music historian Christopher C. King tells of the cosmic connection he hears in two songs of particularly devastating timbre: Greek immigrant Alexis Zoumbas’s haunting instrumental “Epirotiko Mirologi” (1926) and Texan Blind Willie Johnson’s slide guitar masterpiece “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” (1927). Zoumbas is performing a mirologi (an ancient Greek form of lament played to remember the dead) titled after Epirus, his homeland in the Pindus Mountains. Over a bowed bass drone, as King notes, Zoumbas’s violin flutters, weeps, ascends, levitates, and cries “like a wounded bird.” Neither song is a true blues, but they both possess an otherworldly mournfulness, as if drawing the coldest water from the bottom of the same emotional well.

In the magazine: Christopher C. King on Alexis Zoumbas and Blind Willie Johnson.

19 “I FEEL THE SAME”

Bonnie Raitt

Bonnie Raitt is a top-tier songwriter (see “Finest Lovin’ Man” from her debut album, released in 1971), and her slide guitar chops are the envy of many (see “Thing Called Love”). But like all great blues performers, she should also be celebrated for her ability to inhabit and transform other people’s songs and to carry a groove while singing with conviction. Exhibit A: “I Feel the Same” from Raitt’s third album, 1973’s Takin My Time. Chris Smither wrote it and Lowell George takes the lead on slide, but this is Raitt’s song, which she makes clear by her stylish opening acoustic guitar licks and lightly accompanied first verse. As she tells Jewly Hight for a feature in this issue (“Mighty Tight Woman”), “I can only pick songs that really go with what I feel, and it was really important to me to be treated with respect.” The confidence behind her delivery of this song endures in her music today (2016’s Dig in Deep is her twentieth album). It’s a break-up blues, but the blues belongs to the other person: “You won’t forget me or the sound of my name. / Please believe me, I feel the same.”

In the magazine: Jewly Hight on Bonnie Raitt.

20 “TRAMPIN’”

Regina Carter

The traditional gospel song “Trampin’” has seen versions recorded by artists as diverse as Patti Smith, Little Richard, Madeleine Peyroux, and Marian Anderson, but nobody decided to funk it up until jazz violinist Regina Carter (under bassist Jesse Murphy’s arrangement) interpreted the hell out of it for her 2014 album Southern Comfort. Despite the unusual treatment, Carter’s approach to the music on the album reveres its history. She logged time in the Library of Congress listening to Alan Lomax’s and John Work III’s field recordings to study the songs her Alabama mining family might have listened to. During the performance we saw at Christ Episcopal Church in Little Rock, Arkansas, last spring, Carter held up her iPhone to the microphone and played portions of the recordings from which she drew inspiration. In “Trampin’,” Carter weaves the chorus of that prewar spiritual into a hip-hop groove—that’s some old-school sampling.

21 “I’D RATHER GO BLIND”

Etta James

“Funny, but that’s a tune that’s deepened along with my life, its meaning growing more mysterious,” wrote Etta James in her memoir Rage to Survive, published in 1995. “Me and the song have grown old together.” She was writing about “I’d Rather Go Blind,” recorded during her sessions at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, in 1967. By the time she cut what would become one of her signature numbers, James had already had a string of hits with Chess (“At Last,” “Something’s Got a Hold on Me,” “All I Could Do Was Cry”). But “I’d Rather Go Blind” has always felt different—more personal, more soulful, more dark. In her memoir, James gives a clue for why that might be. She tells the story of how she cowrote the song with Ellington Jordan, who started it while he was in prison. She finished it, then declined to take a songwriting credit, a decision she later regretted. “I was blind,” she writes, of the inspiration behind the lyrics. “I was blind in my love life, and I was blind in my personal ways. Like the song says, ‘I just don’t want to be free.’”

22 “SUNFLOWER RIVER BLUES”

John Fahey

As a teenager in Takoma Park, Maryland, in the fifties, fledgling guitarist John Fahey canvassed door-to-door for rare early country-blues records. On his first album, Blind Joe Death, released on his own label, Takoma Records, in 1959, Fahey attributed one side of the LP to the fictional mythic bluesman of the title, a character with a backstory that Fahey would continue to refer to for decades. His was an obsession steeped in intellectual rigor; in grad school at UCLA, he wrote his master’s thesis in folklore about Charley Patton, and in 1963, using a geographical clue from song lyrics, Fahey contacted the forgotten bluesman Bukka White, who was living in Memphis, and recorded him for Takoma. The next year, he went on a road trip through the Deep South with his friends Bill Barth and Henry Vestine, hoping to locate Skip James and learn the secrets of his open tunings. (They found James laid up in a hospital in Tunica, and Fahey recorded him, too.) All the while, Fahey was further developing his own avant-garde sound, which would culminate in his creation of a new genre called American Primitive Guitar, marked by acoustic, instrumental, fingerstyle playing influenced by blues, hymns, and classical music. Fahey maintained an inscrutable and chaotic lifestyle, suffering bouts of poor health. He was given to drink and to disappearing from public view for long spells; he died after undergoing sextuple heart-bypass surgery in 2001, at sixty-one. As he had done to the country-blues heroes of his adolescence, Fahey himself was essentially rediscovered—living in a welfare motel in Salem, Oregon, and routinely pawning his guitar to make rent—by younger admirers in the decade before his death. This version of his classic “Sunflower River Blues” conveys the careful, intricate style and complex, moody compositions that enshrined Fahey as a master guitarist and musical inventor. The Sunflower River flows through western Mississippi, right by Dockery Farms—a sacred spring in the history of the Delta blues.

23 “RAILROAD BILL”

Etta Baker & Cora Phillips

Before the song rolls, Etta Baker makes her point clear: This is no Steamboat Bill, this is Railroad Bill—for to Baker, a black woman born to Reconstruction’s nadir, born to the Southern agrarian working class, born to the blues, the difference between the two folk songs would have been as wide as that between God and the Devil. “Steamboat Bill” was a Leighton Brothers minstrel show standard, a catchy ballad ridiculing the hubris of the main character, of thinking you could ever beat the Robert E. Lee down the Mississippi. But Railroad Bill! Now that was a story: a black man, once lost to Alabama’s for-profit prison system, shot his way out and eluded the hounds of white authority for years while he robbed the railroad rich and gave new hope to the country’s stationary poor. Railroad Bill! Etta Baker seems to say, with all her life pushing into those three thin syllables, all her hot-sun days of Jim Crow and civil rights and Reaganomics, her mother-self, daughter-self, sister-self (Cora Phillips beside her) rising together to say in one man’s name: This is the story of my South.

The Oxford American’s 2016 Southern Music Issue CD would not have been possible without the generosity of the creators and rights holders of these songs. Detailed credits and acknowledgements can be found in the magazine. Liner notes by Maxwell George, Eliza Borné, Jay Jennings, and Rebecca Gayle Howell.