"Beat It" from the Relics series. © 2013 Robert Moran

Frankye's Cookbooks

By Frances Mayes

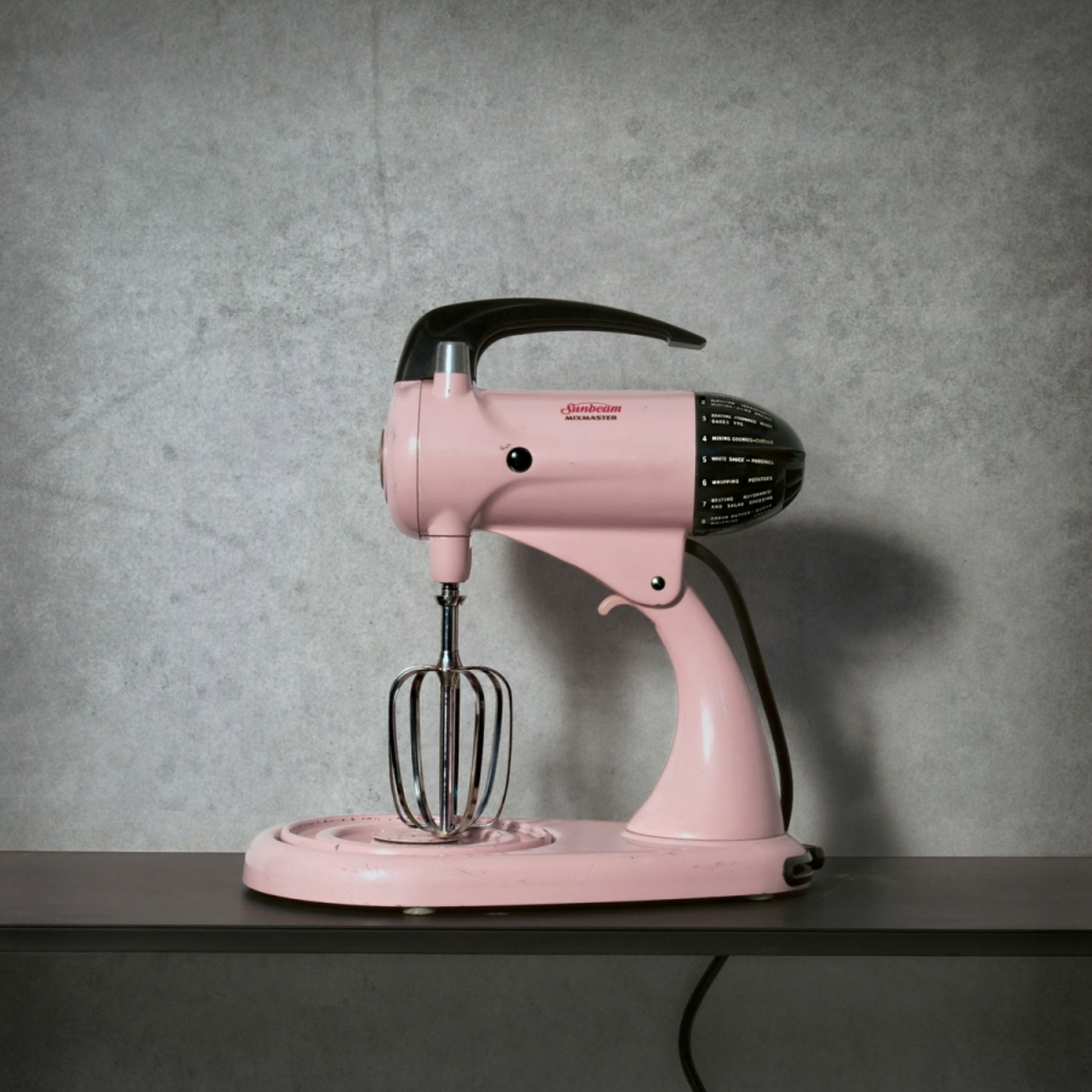

Since I removed myself from San Francisco, where I spent my university-teaching career, and relocated to the South, I am again reveling in the food that my little silver spoon first dipped into down in South Georgia, where everyone in my family knew, and I soon would, too, that dinner, the midday meal, was the event of the day, that Mr. Burnhart got in melons on Wednesday, corn every day of high summer, bushels of lady peas infrequently—you had to reserve—just-dug potatoes from July on, and I came to know also that when Frankye, my mother, pulled into the driveway with her boxes of fresh vegetables, Indian River grapefruits, and yellow plums, surely at the bottom I’d find six or seven coconuts bought for her lavish, triumphant three-layer cake, partly to be achieved by my hammering with an icepick into the eyes of the coconut, draining the milk into a bowl, and separating the meat from the cracked shell, sections of which I formed into boats with sails made of paper and toothpicks that would not stay glued but still served as clumsy decorations around the cake as, borne aloft, it was brought into the dining room after Sunday dinner, the ritualized meal that only occasionally varied (perhaps a ham or roast beef) from the fried chicken, rice and gravy, butter beans, biscuits, and Depression-glass dishes of peach, watermelon rind, and bread-and-butter pickles, sharp hits of acidity to weigh in against crisp browned chicken, cream gravy, and the sugar bomb of dessert: pecan pie, caramel cake, Lane cake, or the famous coconut with its soft, buttery layers, filling like whipped clouds and the crunch of fresh coconut reminding us, way in the heart of Dixie, that somewhere dwelled the word “exotic,” some clime where the sun might be more demonic than here, where I often heard “dammit” from the kitchen as mother and our cook, Willie Bell, endeavored to force egg whites into meringue on a day when the humidity index tried to climb higher than one hundred percent, causing the Baked Alaska to fail, pie dough to clump, and cream to refuse to form peaks, sending my mother to note in her Central Methodist Church cookbook: Do Not Attempt on a Humid Day—then to slam the book and shove it into the kitchen drawer which served as a library for her entire collection of cookbooks, an astonishingly meager array of two church missionary circle publications; the Westinghouse Automatic Electric Range recipe collection; the Knox Acidulated Gelatine brochure, from which nothing made it into her repertoire; Meals Tested, Tasted, and Approved from the Good Housekeeping Institute; and various refrigerator and baking powder brochures, all stuffed with yellowed and crumbling newspaper clippings, with the endpapers and blank spaces covered in Frankye’s hand-written recipes, along with her other favorites written on the backs of checks, notepaper, stationery filched from the Sheraton Plaza Hotel in Daytona Beach, and hourly agenda pages torn from a life insurance daybook—that’s it, the only records she kept, her magnificent talent for feeding us and friends and the sick and the dead’s families recorded on paper scraps and interspersed with the books’ absurd printed tips to wear long fur if you are tall and to carry a slender umbrella if you are stout, all of which I now keep (what would I grab if the house caught fire?) in my bookcase of four hundred cookbooks, those totems of my thousands of dinner parties, holidays, celebrations—how can it be: she remains the better cook—my great collection shelved with the basket holding her penciled, telegraphic words I always dive into when I long for her squash casserole (today), pecan pie, country captain chicken, or even better, classic chicken Divan, wedding cookies dusted with XXXX sugar, cheese biscuits, corn pudding, or at Christmas when I recall most vividly her Martha Washington jetties, divinity, nutty fudge, bourbon balls, and peanut brittle, each recipe jotted down quickly, a minimalist document often omitting basic instructions, even ingredients, because she knew, and you should, too, you viewer of long-ago activity in one seven-windowed, gaily café-curtained kitchen in the now-lost—some would say good riddance—South, way back when I took it all for granted (and sat at the table with a hidden book open on my lap) as the door of the dining room swung open, as splendid platters appeared of smothered quail surrounded by fried potato croquettes, cornbread dressing stuffed inside the gleaming bronze turkey garlanded with cranberry swags, spoon bread, black bottom pie (recorded in my older sister’s aqua ink), brown sugar muffins—always the sweet grace note offered at our table—oyster stew, spicy corn, marshmallow fudge cake, pressed chicken (recognized later in France as galantine), pork loin barbecued overnight at “Uncle” (read: honorific for an older black man) Nathan’s, where he placed the meat on rusty mattress springs over a fiery pit and turned it with a pitchfork, frozen fruit salad, chocolate ice-box cake, Brunswick stew, tomato aspic, and pink-frosted pound cake surrounded by white camellias (always on my March birthday)—yes, all this, but no pasta, except sometimes spaghetti, no microgreens, no sustainable fish, few herbs, which I use copiously, no cheeses but cheddar and hoop cheese—my kitchen runs on parmigiano—no artichokes, mangos, avocados, out-of-season grapes, no food processor, stick blender, mandoline, parchment paper, non-stick pans, icemaker, whisks, no espresso maker, though Frankye did have an ice cream machine that I had to sit on to steady it when she cranked the handle, and she did have a meat grinder, a canning vat, and a Mixmaster so sturdy it probably would be running to this day if it had not been lost, as almost all else was lost, when my mother cooked no more, the yellow kitchen darkened and the house stood vacant, then suddenly sold so quickly that I only salvaged the cast-iron “spider” skillets and the recipes, not the rest, the small stash of tins where she stored paprika, Old Bay Seasoning, tarragon, mace, nutmeg, and red pepper flakes, gone, the pitcher for pineapple tea gone, the eggbeater, dented aluminum press for cheese straws, the timbale iron for savory fried rosettes to cover with chicken à la king gone, the angel food cake pan, the strawberry charlotte mold gone, all taken under the giant, oblivious blue wave that breaks hard when it breaks, then withdraws, pulling everything out far into the deceptive calm of memory, whose flood tides no moon can sway.

Enjoy this story? Explore the OA archive.