Searching the Desert for the Blues

By Peter Guralnick

Blues really was the transformation of my life.

When I was fifteen or sixteen, a friend and I just kind of stumbled onto the music. It was the beginning of the folk revival—1959 or 1960—and somehow in the midst of all that wholesomeness, we fell into the blues.

To this day I don’t know what it was exactly—I had never heard anything quite like it. But it just grabbed me. It completely turned me around. Lightnin’ Hopkins and Big Bill Broonzy, Leadbelly and Blind Lemon Jefferson. Muddy Waters and Little Walter and Howlin’ Wolf. And Blind Willie McTell.

Now, they were all wonderful. Truly wonderful, in the sense of “full of wonder”—which was the state in which my friend and I perpetually found ourselves as we listened, open-mouthed, to the music. Maybe it was the directness of the conversation. Maybe it was the stark, unadorned and unenhanced reality that each of these artists embraced, reality in all of its multifarious beauty, ugliness, and undifferentiated truth.

There was something about the way in which harsh facts could be transmuted into metaphor, pain into joy, a simple three- or four-chord structure and AAB verse that almost anybody could grasp was able to open up into an unfathomable realm of exploration that I had never encountered before. Well, let me quote James Baldwin, whom I read at almost exactly the same time, on the uplifting song of a community in which imagination and self-invention trumped pedigree, in which there existed what Baldwin calls “a zest and a joy and a capacity for facing and surviving disaster . . . very moving and very rare. Perhaps we were all of us,” he reflected in The Fire Next Time, “pimps, whores, racketeers, church members and children—bound together by the nature of our oppression.” If so, it was that inescapably shared heritage, Baldwin went on, that helped create the dynamic that allowed one “to respect and rejoice in . . . life itself, and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread.”

In other words, the indomitable spirit, among other things, of the blues. It was, as Baldwin wrote in his short story “Sonny’s Blues,” a tale that is “never new [but] must always be heard . . . it’s the only light we’ve got in all this darkness.”

But for all that commonality of spirit—and the blues truly is a shared heritage in a sense that few are willing to recognize in this proprietary age: “NOBODY,” as Bob Dylan proclaimed, “can sing the blues like Blind Willie McTell.”

Let me give you a little bit of our take on Blind Willie McTell—his music, not the myth that we constructed from it. (I’ll get to the myth in a moment.) The first song I ever heard by Blind Willie McTell was his masterpiece, “Statesboro Blues,” though so many of his songs can rightly be called masterpieces. What was so striking about “Statesboro Blues,” then and now, was its utter unclassifiability. I suppose that’s true of all great art, from Gerard Manley Hopkins to Robert Johnson, from Alice Munro to Howlin’ Wolf. But the thing about “Statesboro Blues” was that, as much as you might be able to locate some of its disparate elements—the “going up the country” theme, for example, seems to have originated with Sippie Wallace (though who knows where Sippie Wallace got it from)—there was no Venn diagram, there was no blueprint that could tell you how to put it all back together again.

Propelled by McTell’s ringing, delicately accented twelve-string guitar, “Statesboro Blues” is an epic tale of dislocation and commonality (“Brother got ‘em, friends got ‘em / I got ‘em / Woke up this morning, we had them Statesboro blues / I looked over in the corner / Grandma and Grandpa had ‘em, too”) that’s most familiar to contemporary listeners in the Allman Brothers’ inexorably anthemic version. Here, though, it is presented with such charm, such casual beauty, such utter lack of predictability—lyrical, metrical, thematic—that it surprises every time. There’s a plaintiveness, too, not normally associated with the blues, not just in the high, slightly nasal voice that delivers the lyrics with an uncommon purity and precision but in the lilting, melodic approach to a number that still possesses as much inarguable authenticity as the most affecting of “deep blues.”

I think that was what intrigued me most about Blind Willie McTell’s work—the way in which it could combine both unapologetic winsomeness and undisguised profundity. It was clever, it could suggest grace, humor, sexual suggestiveness, sometimes even menace—all with equal authority. But at its heart, it possessed a core of both delicacy and tensile strength; McTell brought to it a subtlety of approach rarely associated with the powerhouse impact of the twelve-string guitar. Above all, he displayed a breadth of imagination that allowed him to cover virtually every aspect not just of the African-American experience but of the entire American vernacular tradition.

He sang everything from blues to ragtime to popular songs of the day and sentimental numbers of yesteryear, from hillbilly yodels to way-back spirituals and moans, in addition, of course, to one of his specialties, a breezy form of recitatif that could pass for the rap of its day. And he could do it all at the drop of a hat. He could play the part of a pimp, a gambler, a nightclub roue, or a roving cowboy—with wit, imagination, a knowing wink of complicity, or an air of irrefutable authority. Or he could provide us with a sly original like “Travelin’ Blues,” which takes us on a tour of what he calls “South America” (in other words, the American South), with all of its implicit allusions to the lives that were led, the stories that could be told, even as the guitar summons up the sounds of the landscape, and the crying of the slide guitar suggests a whole unspoken subtext lying just beneath the surface.

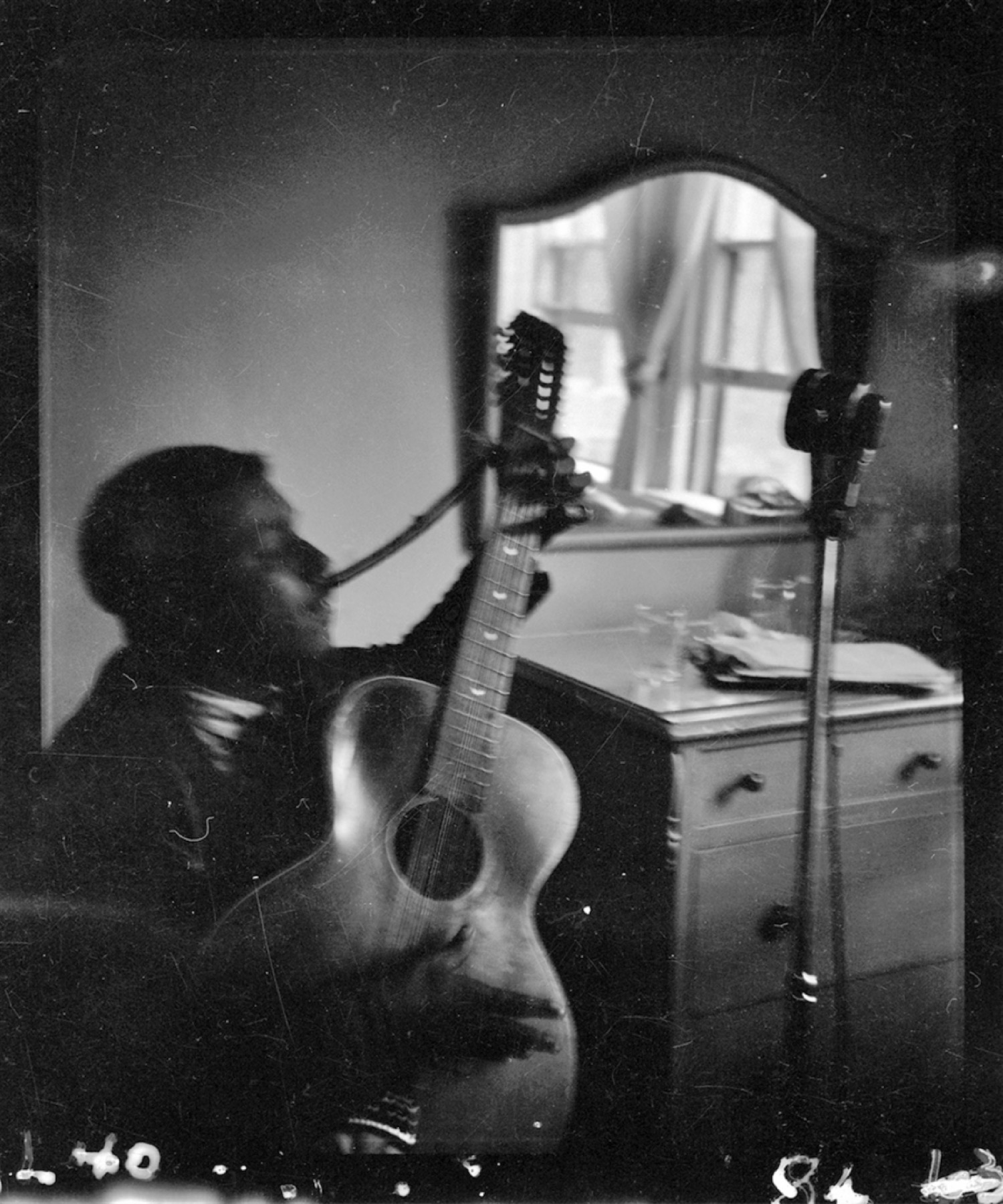

In 1940, he recorded a tantalizing session for the Library of Congress that came about only because folklorist John Lomax’s wife, Ruby, spotted “a Negro man with a guitar” at the Pig ‘n Whistle barbecue stand (Pig ‘n Whistle Red was another one of his latter-day sobriquets) and Blind Willie agreed to record some numbers, since business at the drive-in was slow. The result was a melange of folk songs, rags, spirituals, pop, and pre-blues material, interspersed with monologues revealing not just his astonishing powers of recall but an analytic approach to what John Lomax labeled “history of the blues [and] life as a maker of records.”

Just listening to a little bit of this interview—with the understanding that Blind Willie felt, for good reason, I think, that his interviewer was trying to put him in a “trick bag” (Lomax was doing his very best to get songs of social protest out of his subject, something I would imagine McTell might have considered bad for business)—provides a fascinating glimpse not only of a career in music but of a reflective and highly individuated life, and one can only wish there could have been more. But we are at least hearing the real voice of Blind Willie McTell. Or, one is led sometimes to wonder by the sly confidence with which he presents his conclusions (“I am talking about the days of years ago—how from 19 and 8 on up . . . blues have started to be original”), are we?

But I said before I was going to talk a little bit about the myth we built up around him. Well, I know this is going to sound silly, but the Blind Willie McTell we constructed when we first encountered him was kind of like a ghost rider who, whatever his real-life state of corporeality, would go on forever, in defiance of all the immutable laws of human existence. I know, I know. I said this was going to sound silly. And, of course, it was based on a number of serious fundamental misconceptions—but most of all it was based on the power of the music and the romantic illusion that I still fall back on from time to time: that the dauntless, unvanquishable spirit that created all that music, that propelled Blind Willie and Blind Samuel and Barrelhouse Sammy (The Country Boy) and Hot Shot Willie into all those recording sessions, could somehow never be stilled. Because one of the most remarkable facts about the actual life of Blind Willie McTell—and this was about the only fact that we knew about him for a long time—was that he continued to record year after year, decade after decade, from his first session for Victor in 1927 (“I continued my playing up until 19 and 27, the 18th day of October, when I made records for the Victor Record people”) to his last for an Atlanta record store owner in 1956. And this was without hits to sustain him, without the kind of record company enthusiasm that a first-generation blues star like Blind Lemon Jefferson or later ones like Leroy Carr or Big Bill Broonzy would receive, and, perhaps most important, without the kind of posthumous boost you’re likely to attract if word gets around that you have sold your soul to the devil, as it did for Robert Johnson some thirty years after his death.

Blind Willie McTell simply kept showing up—and showing up under all those unlikely pseudonyms. I mean, how could anyone that determined not to go away ever die? And how were we to know that in fact he had died shortly before we even discovered his music? We certainly could never have guessed that his real name was McTier, or McTear—or dreamt that he made a decent living from his craft (for many years he played regularly for the white patrons of the Pig ‘n Whistle where John Lomax found him, as well as for black audiences at the famed 81 Theatre in Atlanta).

Because Blind Willie McTell was in fact a professional entertainer. Even more to the point, he was something we could never have imagined at the time: a well-educated, well-read, self-sufficient bluesman, who, as blues scholar David Evans has pointed out, put his wife, Kate, through nursing school, had a solid, supportive network of family and friends to sustain him in good times and bad, and led a life that in our youthful naivete it would have been almost impossible for us to conceive of, a life that incorporated both order and art.

Well, it’s still a little difficult to conceive of, and if it was our naivete then, to some extent it continues to be a commonplace misconception, simply because, as blues singer Johnny Shines once said, so many who profess to love the blues insist that it is nothing more than a primitive music, its practitioners outcasts by both choice and definition, though Johnny Shines for one didn’t consider himself an outcast in the least. “I play the blues,” he said, “but I don’t feel that the blues is dirty. Society decided for us that the blues was dirty.” And he was determined to disprove that notion, he said, by consciously and illuminatingly carrying the music on.

At some point in my own education I discovered the limitations of just theorizing about the music—sitting in your room and mulling over lyrics you could never fully decipher or going to see Lightnin’ Hopkins perform at a college concert (he was the first blues singer I ever saw, and I can tell you—he was awesome). The way that we had been introduced to the music, the blues was dead almost by definition because we had encountered it only on records—we never heard it on the radio; it wasn’t presented, like rock & roll, say, at shows. It seemed somehow as if it was something that had been tucked safely away in the past (even if in many cases it was the very recent past), a subject for historical study, however passionate that study might be.

The light only dawned for me with the coming of soul music (Otis Redding, Solomon Burke, Joe Tex), first on the radio, then with the first soul revue I ever saw, the 1964 Hot Summer Shower of Stars, with Solomon as the headliner and both Joe and Otis (and many, many others) on the bill. It has long been my firmest belief that in order to write—fiction, nonfiction, it doesn’t matter—you need to make the empathetic leap. But, really, in order to live you have to make that same leap, whether or not in certain harsh literary and political circles “empathy” has become a dirty word. Well, I can tell you, I made that jump as if I were getting ready for the Empathy Olympics, without either hesitation or fear. From that soul revue on, I attended every show that came to town. After being offered the opportunity, I even started to usher the shows, a formidable challenge for an excruciatingly self-conscious twenty-year-old. But the music allowed me to overcome my inhibitions, or at least ignore them for as long as the moment lasted. And the music in almost every case sprang directly from the living tradition of the blues—and of course, the church, from which the blues ultimately sprang. “There is no music like that music,” Baldwin also wrote, “no drama like the drama of the saints rejoicing . . . [nothing] to equal the fire and excitement that sometimes, without warning, fill a church, causing the church, as Leadbelly and so many others have testified, to ‘rock.’”

Which leads more or less directly to Blind Willie McTell’s fellow Georgian James Brown, hailing, as he frequently declared, from “Augusta, GA.” (As McTell told John Lomax, “I was born at Thomson, Georgia, 134 miles from Atlanta and 37 miles west of Augusta.”) I don’t think I have to tell any present-day aficionado with the slightest acquaintance with YouTube how cataclysmic it was to see the James Brown Show in 1965. But back then, in a prehistoric world in which James Brown and Howlin’ Wolf and Big Joe Turner were barred not just from mainstream acceptance but from mainstream notice, I really did feel compelled to tell the world. That’s why I first started writing about music: to proclaim to the world how great that music was. I think the first story I ever wrote for print was about James Brown, and it was intended solely to draw people to something that for me was the most electrifying theatrical event I had ever witnessed—and remains so. In an age of Happenings—legitimate theater was increasingly intended at that time to be eruptive and spontaneous—there was nothing that could hold a candle to the theatrics that exploded every time James Brown set foot onstage. The ferocity of his energy, the uncompromising commitment he gave to every show, the hypnotic quality of his incantatory performance, the ongoing drama of death and resurrection that he enacted night after night, every night, onstage—well, everyone has their own memories to fall back on, whether of James Brown, or of some other equally electrifying performer. (I mean, come on, I can’t imagine anyone that electrifying!) But the point is, none of that pushed out—I’m sure James Brown would have been the first to insist: it all built on—Blind Willie McTell. And Louis Jordan. And Sister Rosetta Tharpe. On a tradition that whether or not it is likely to be explicitly acknowledged, or even recognized, by contemporary artists or audiences, remains the underpinning for so much of the music that continues to provide us with inspiration today.

Sometimes I think about what might have happened if Blind Willie McTell had lived for just a few more years. He died just short of the 1960s blues revival in which long-forgotten, or never-known, artists like Son House, Skip James, Sleepy John Estes, and Mississippi John Hurt were rediscovered and celebrated—and contemporary performers like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf found entirely new careers. Think of what Blind Willie McTell might have made of that kind of opportunity. With his wit, charm, insouciance, and native capacity for adaptation, one could imagine him as a rediscovered superstar, the James Brown of the country blues movement. But in a sense that’s a misreading not just of the blues but of the entire span and tradition of American vernacular music, from Charley Patton to Bill Monroe, from Hank Williams to Chuck Berry, from Mahalia Jackson to Elvis Presley.

The blues, as Blind Willie McTell attempted in his own way to explain in that vexed interview with John Lomax, is above all a tradition in which generation after generation has participated. It is a homemade music not all that different from the music of James Brown that calls up all sorts of common memories and was bred on the call-and-response pattern (originating in both the church and the cotton field) in which the audience’s response is nearly as important as the singer’s call. Above all, it has always been a music centered around the human voice, made on whatever instruments are available, taking whatever situations and conditions are at hand and transforming them by sheer force of imaginative will, seeking not to deny those conditions but to transcend them by celebrating the diversity, the creativity, the spontaneity and indomitability of a culture that simply refused to allow itself to be defined by its oppressors. As James Brown proclaimed, “I’m black and I’m proud.” Which, racial specificity aside, was in a very real sense the whole thrust of rock & roll, too, the music that for the first time fused the traditions of everyone, black and white, who had ever been denied a place at the table. Think of Carl Perkins, in the midst of the genial nursery-rhyme versification of “Blue Suede Shoes,” coming back again and again with the same message of good-humored pride and defiance: Whatever you do, don’t you step on my blue suede shoes. Or as Merle Haggard would declare, in a somewhat different context but with no less personal or poetic conviction, “I Take a Lot of Pride in What I Am.”

More and more, we are a culture of lists. There’s always got to be a No. 1. There always has to be a “Best.” I remember a few years ago—well, it’s fifteen years ago now—at the time of the much-vaunted millennium, I got all kinds of calls from mainstream magazines and periodicals (yes, they still existed then) who wanted to know about Elvis mostly, because of my recent biography. Was he the entertainer of the century? Or maybe even of the millennium?

Well, I don’t know. I suppose I could have said, No, it was James Brown. Or Blind Willie McTell. Or Merle Haggard. Or Solomon Burke. But that would have been falling into the same trap. The point that I made to each and every one of them—and perhaps it should come as no great surprise that it was not quoted by a single one—was that Elvis alone wasn’t the point. That if Elvis, a blues-influenced musician if ever there was one, had achieved anything, if there was one thing of which he was unquestionably proud, it was that he contributed to a cultural revolution as significant as anything that we have witnessed in our time, a cultural revolution in which blues (and bluegrass, and gospel, and country music, and jazz, and soul) was very much in the forefront. Because looking back on it, the twentieth century clearly saw the triumph of American vernacular music—a near-global recognition that here was America’s greatest cultural contribution to the world, with the blues serving as both an underpinning and a common language that at its best continues to represent the polyglot nature of true democracy.

And Blind Willie McTell? Despite everything I’ve said, and all the facts that I’ve learned, I’ve got to admit I still expect him to turn up—in one of his many guises, under one of his innumerable pseudonyms. And, you know, the funny thing is, in his own way he does. Every time we hear his voice, every time we encounter the persistence of his music, the truth of his vision, the triumph of his hard-won art, it announces over and over again, in its own way, the casual beauty of the illimitable. That’s what Blind Willie McTell, or Blind Samuel, or Pig ‘n Whistle Red, or Georgia Bill still has to offer. Who’s to say that one or another of them won’t show up on our doorstep tomorrow?

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.