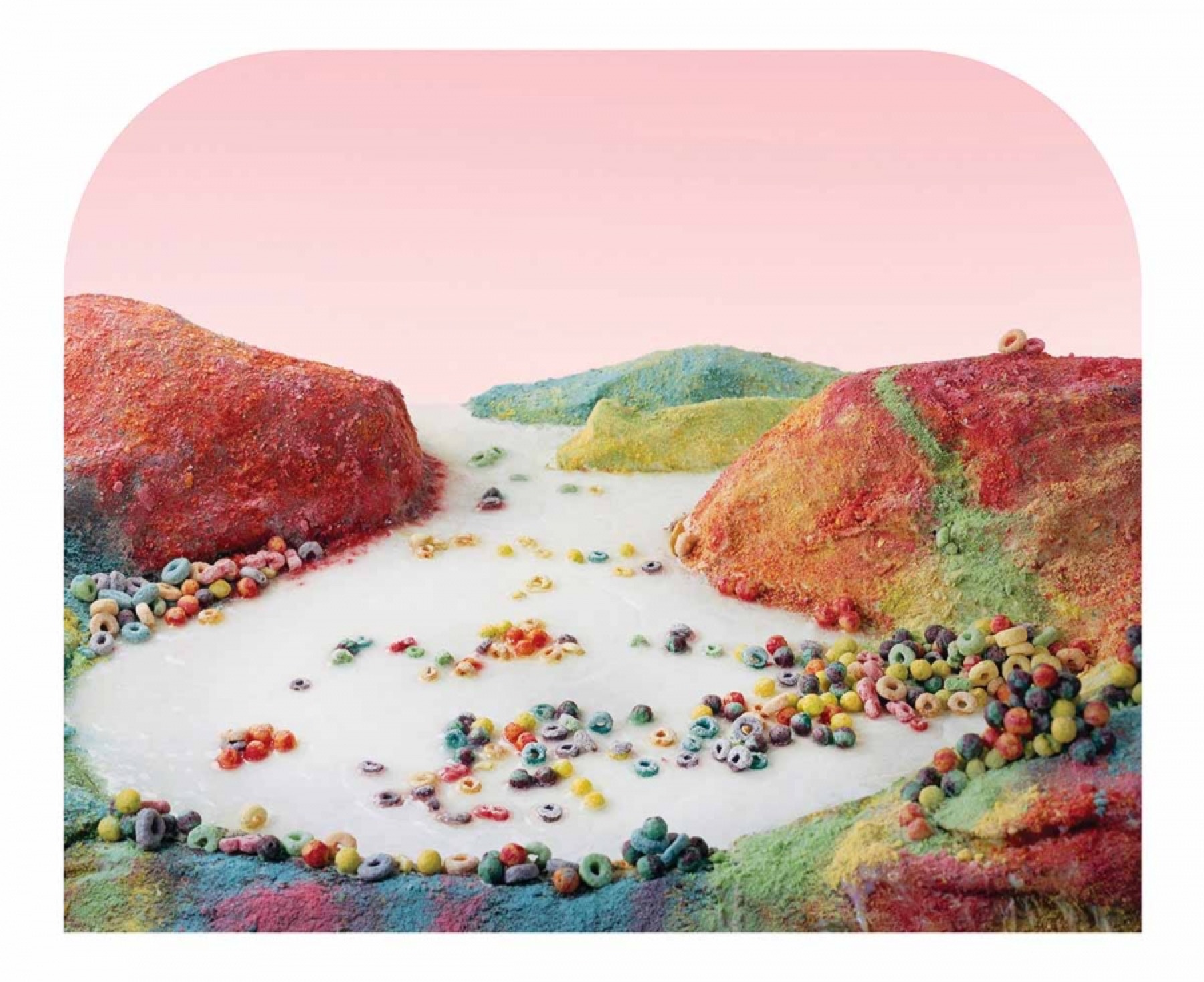

“Fruit Loops Landscape,” by Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman, from the series Processed Views: Surveying the Industrial Landscape

Trash Food

By Chris Offutt

Over the years I’ve known many people with nicknames, including Lucky, Big O, Haywire, Turtle Eggs, Hercules, two guys named Hollywood, and three guys called Booger. I’ve had my own nicknames as well. In college people called me “Arf” because of a dog on a t-shirt. Back home a few of my best buddies call me “Shit-for-Brains,” because our teachers thought I was smart.

Three years ago, shortly after moving to Oxford, someone introduced me to John T. Edge. He goes by his first name and middle initial, but I understood it as a nickname—Jaunty. The word “jaunty” means lively and cheerful, someone always merry and bright. The name seemed to suit him perfectly. Each time I called him Jaunty he gave me a quick sharp look of suspicion. He wondered if I was making fun of his name—and of him. The matter was resolved when I suggested he call me “Chrissie O.”

Last spring John T. asked me to join him at an Oxford restaurant. My wife dropped me off and drove to a nearby secondhand store. Our plan was for me to meet her later and find a couple of cheap lamps. During lunch John T. asked me to give a presentation at the Southern Foodways Alliance symposium over which he presided every fall.

I reminded him that I lacked the necessary qualifications. At the time I’d only published a few humorous essays that dealt with food. Other writers were more knowledgeable and wrote with a historical context, from a scholarly perspective. All I did was write personal essays inspired by old community cookbooks I found in secondhand stores. Strictly speaking, my food writing wasn’t technically about food.

John T. said that didn’t matter. He wanted me to explore “trash food,” because, as he put it, “you write about class.”

I sat without speaking, my food getting cold on my plate. Three thoughts ran through my mind fast as flipping an egg. First, I couldn’t see the connection between social class and garbage. Second, I didn’t like having my thirty-year career reduced to a single subject matter. Third, I’d never heard of anything called “trash food.”

I write about my friends, my family, and my experiences, but never with a socio-political agenda such as class. My goal was always art first, combined with an attempt at rigorous self-examination. Facing John T., I found myself in a professional and social pickle, not unusual for a country boy who’s clawed his way out of the hills of eastern Kentucky, one of the steepest social climbs in America. I’ve never mastered the high-born art of concealing my emotions. My feelings are always readily apparent.

Recognizing my turmoil, John T. asked if I was pissed off. I nodded and he apologized immediately. I told him I was overly sensitive to matters of social class. I explained that people from the hills of Appalachia have always had to fight to prove they were smart, diligent, and trustworthy. It’s the same for people who grew up in the Mississippi Delta, the barrios of Los Angeles and Texas, or the black neighborhoods in New York, Chicago, and Memphis. His request reminded me that due to social class I’d been refused dates, bank loans, and even jobs. I’ve been called hillbilly, stumpjumper, cracker, weedsucker, redneck, and white trash—mean-spirited terms designed to hurt me and make me feel bad about myself.

As a young man, I used to laugh awkwardly at remarks about sex with my sister or the perceived novelty of my wearing shoes. As I got older I quit laughing. When strangers thought I was stupid because of where I grew up, I understood that they were granting me the high ground. I learned to patiently wait in ambush for the chance to utterly demolish them intellectually. Later I realized that this particular battle strategy was a waste of energy. It was easier to simply stop talking to that person—forever.

But I didn’t want to do that with a guy whose name sounds like “jaunty.” A guy who’d inadvertently triggered an old emotional response. A guy who liked my work well enough to pay me for it.

By this time our lunch had a tension to it that draped over us both like a lead vest for an X-ray. We just looked at each other, neither of us knowing what to do. John T. suggested I think about it, then graciously offered me a lift to meet my wife. But a funny thing had happened. Our conversation had left me inexplicably ashamed of shopping at a thrift store. I wanted to walk to hide my destination, but refusing a ride might make John T. think I was angry with him. I wasn’t. I was upset. But not with him.

My solution was a verbal compromise, a term politicians use to mean a blatant lie. I told him to drop me at a restaurant where I was meeting my wife for cocktails. He did so and I waited until his red Italian sports car sped away. As soon as he was out of sight I walked to the junk store. I sat out front like a man with not a care in the world, ensconced in a battered patio chair staring at clouds above the parking lot. When I was a kid my mother bought baked goods at the day-old bread store and hoped no one would see her car. Now I was embarrassed for shopping secondhand.

My behavior was class-based twice over: buying used goods to save a buck and feeling ashamed of it. I’d behaved in strict accordance with my social station, then evaluated myself in a negative fashion. Even my anger was classic self-oppression, a learned behavior of lower-class people. I was transforming outward shame into inner fury. Without a clear target, I aimed that rage at myself.

My thoughts and feelings were completely irrational. I knew they made no sense. Most of what I owned had belonged to someone else—cars, clothes, shoes, furniture, dishware, cookbooks. I liked old and battered things. They reminded me of myself, still capable and functioning despite the wear and tear. I enjoyed the idea that my belongings had a previous history before coming my way. It was very satisfying to repair a broken lamp made of popsicle sticks and transform it to a lovely source of illumination. A writer’s livelihood is weak at best, and I’d become adept at operating in a secondhand economy. I was comfortable with it.

Still, I sat in that chair getting madder and madder. After careful examination I concluded that the core of my anger was fear—in this case fear that John T. would judge me for shopping secondhand. I knew it was absurd since he is not judgmental in the least. Anyone can see that he’s an open-hearted guy willing to embrace anything and everyone—even me.

Nevertheless I’d felt compelled to mislead him based on class stigma. I was ashamed—of my fifteen-year-old Mazda, my income, and my rented home. I felt ashamed of the very clothes I was wearing, the shoes on my feet. Abruptly, with the force of being struck in the face, I understood it wasn’t his judgment I feared. It was my own. I’d judged myself and found failure. I wanted a car like his. I wanted to dress like him and have a house like his. I wanted to be in a position to offer other people jobs.

The flip side of shame is pride. All I had was the pride of refusal. I could say no to his offer. I did not have to write about trash food and class. No, I decided, no, no, no. Later, it occurred to me that my reluctance was evidence that maybe I should say yes. I resolved to do some research before refusing his offer.

John T. had been a little shaky on the label of “trash food,” mentioning mullet and possum as examples. At one time this list included crawfish because Cajun people ate it, and catfish because it was favored by African Americans and poor Southern whites. As these cuisines gained popularity, the food itself became culturally upgraded. Crawfish and catfish stopped being “trash food” when the people eating it in restaurants were the same ones who felt superior to the lower classes. Elite white diners had to redefine the food to justify eating it. Otherwise they were voluntarily lowering their own social status—something nobody wants to do.

It should be noted that carp and gar still remain reputationally compromised. In other words—poor folks eat it and rich folks don’t. I predict that one day wealthy white people will pay thirty-five dollars for a tiny portion of carp with a rich sauce—and congratulate themselves for doing so.

I ran a multitude of various searches on library databases and the Internet in general, typing in permutations of the words “trash” and “food.” Surprisingly, every single reference was to “white trash food.” Within certain communities, it’s become popular to host “white trash parties” where people are urged to bring Cheetos, pork rinds, Vienna sausages, Jell-O with marshmallows, fried baloney, corndogs, RC cola, Slim Jims, Fritos, Twinkies, and cottage cheese with jelly. In short—the food I ate as a kid in the hills.

Participating in such a feast is considered proof of being very cool and very hip. But it’s not. Implicit in the menu is a vicious ridicule of the people who eat such food on a regular basis. People who attend these “white trash parties” are cuisinally slumming, temporarily visiting a place they never want to live. They are the worst sort of tourists—they want to see the Mississippi Delta and the hills of Appalachia but are afraid to get off the bus.

The term “white trash” is an epithet of bigotry that equates human worth with garbage. It implies a dismissal of the group as stupid, violent, lazy, and untrustworthy—the same negative descriptors of racial minorities, of anyone outside of the mainstream. At every stage of American history, various groups of people have endured such personal attacks. Language is used as a weapon: divisive, cruel, enciphered. Today is no different. For example, here in Mississippi, the term “Democrats” is code for “African Americans.” Throughout the U.S.A., “family values” is code for “no homosexuals.” The term “trash food” is not about food, it’s coded language for social class. It’s about poor people and what they can afford to eat.

In America, class lines run parallel to racial lines. At the very bottom are people of color. The Caucasian equivalent is me—an Appalachian. As a male Caucasian in America, I am supposed to have an inherent advantage in every possible way. It’s true. I can pass more easily in society. I have better access to education, health care, and employment. But if I insist on behaving like a poor white person—shopping at secondhand shops and eating mullet—I not only earn the epithet of “trash,” I somehow deserve it.

The term “white trash” is class disparagement due to economics. Polite society regards me as stupid, lazy, ignorant, violent and untrustworthy.

I am trash because of where I’m from.

I am trash because of where I shop.

I am trash because of what I eat.

But human beings are not trash. We are the civilizing force on the planet. We produce great art, great music, great food, and great technology. It’s not the opposable thumb that separates us from the beasts, it’s our facility with language. We are able to communicate with great precision. Nevertheless, history is fraught with the persistence of treating fellow humans as garbage, which means collection and transport for destruction. The most efficient management of humans as trash occurred when the Third Reich systematically murdered people by the millions. People they didn’t like. People they were afraid of. Jews, Romanis, Catholics, gays and lesbians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the disabled.

In World War II, my father-in-law was captured by the Nazis and placed on a train car so crammed with people that everyone had to stand for days. Arthur hadn’t eaten in a week. He was close to starvation. A Romani man gave him half a turnip, which saved his life. That Romani man later died. Arthur survived the war. He had been raised to look down on Romani people as stupid, lazy, violent, and untrustworthy—the ubiquitous language of class discrimination. He subsequently revised his view of Romanis. For Arthur, the stakes of starvation were high enough that he changed his view of a group of people. But the wealthy elite in this country are not starving. When they changed their eating habits, they didn’t change their view of people. They just upgraded crawfish and catfish.

Economic status dictates class and diet. We arrange food in a hierarchy based on who originally ate it until we reach mullet, gar, possum, and squirrel—the diet of the poor. The food is called trash, and then the people are.

When the white elite take an interest in the food poor people eat, the price goes up. The result is a cost that prohibits poor families from eating the very food they’ve been condemned for eating. It happened with salmon and tuna years ago. When I was a kid and money was tight, my mother mixed a can of tuna with pasta and vegetables. Our family of six ate it for two days. Gone are the days of subsisting on cheap fish patties at the end of the month. The status of the food rose but not the people. They just had less to eat.

What is trash food? I say all food is trash without human intervention. Cattle, sheep, hogs, and chickens would die unless slaughtered for the table. If humans didn’t harvest vegetables, they would rot in the field. Food is a disposable commodity until we accumulate the raw material, blend ingredients, and apply heat, cold, and pressure. Then our bodies extract nutrients and convert it into waste, which must be disposed of. The act of eating produces trash.

In the hills of Kentucky we all looked alike—scruffy white people with squinty eyes and cowlicks. We shared the same economic class, the same religion, the same values and loyalties. Even our enemy was mutual: people who lived in town. Appalachians are suspicious of their neighbors, distrustful of strangers, and uncertain about third cousins. It’s a culture that operates under a very simple principle: you leave me alone, and I’ll leave you alone. After moving away from the hills I developed a different way of interacting with people. I still get cantankerous and defensive—ask John T.— but I’m better with human relations than I used to be. I’ve learned to observe and listen.

As an adult I have lived and worked in eleven different states—New York, Massachusetts, Florida, New Mexico, Montana, California, Tennessee, Georgia, Iowa, Arizona, and now Mississippi. These circumstances often placed me in contact with African Americans as neighbors, members of the same labor crew, working in restaurants, and now university colleagues. The first interaction between a black man and a white man is one of mutual evaluation: does the other guy hate my guts? The white guy—me—is worried that after generations of repression and mistreatment, will this black guy take his anger out on me because I’m white? And the black guy is wondering if I am one more racist asshole he can’t turn his back on. This period of reconnaissance typically doesn’t last long because both parties know the covert codes the other uses—the avoidance of touch, the averted eyes, a posture of hostility. Once each man is satisfied that the other guy is all right, connections begin to occur. Those connections are always based on class. And class translates to food.

Last year my mother and I were in the hardware store buying parts to fix a toilet. The first thing we learned was that the apparatus inside commodes has gotten pretty fancy over the years. Like breakfast cereal, there were dozens of types to choose from. Toilet parts were made of plastic, copper, and cheap metal. Some were silent and some saved water and some looked as if they came from an alien spacecraft.

A store clerk, an African-American man in his sixties, offered to help us. I told him I was overwhelmed, that plumbing had gotten too complicated. I tried to make a joke by saying it was a lot simpler when everyone used an outhouse. He gave me a quick sharp look of suspicion. I recognized his expression. It’s the same one John T. gave me when I mispronounced his name, the same look I gave John T. when he mentioned “trash food” and social class. The same one I unleashed on people who called me a hillbilly or a redneck.

I understood the clerk’s concern. He wondered if I was making a veiled comment about race, economics, and the lack of plumbing. I told him that back in Kentucky when the hole filled up with waste, we dug a new hole and moved the outhouse to it. Then we’d plant a fruit tree where the old outhouse had been.

“Man,” I said, “that tree would bear. Big old peaches.”

He looked at me differently then, a serious expression. His earlier suspicion was gone.

“You know some things,” he said. “Yes you do.”

“I know one thing,” I said. “When I was a kid I wouldn’t eat those peaches.”

The two of us began laughing at the same time. We stood there and laughed until the mirth trailed away, reignited, and brought forth another bout of laughter. Eventually we wound down to a final chuckle. We stood in the aisle and studied the toilet repair kits on the pegboard wall. They were like books in a foreign language.

“Well,” I said to him. “What do you think?”

“What do I think?” he said.

I nodded.

“I think I won’t eat those peaches.”

We started laughing again, this time longer, slapping each other’s arms. Pretty soon one of us just had to mutter “peaches” to start all over again. Race was no more important to us than plumbing parts or shopping at a secondhand store. We were two Southern men laughing together in an easy way, linked by class and food.

On the surface, John T. and I should have been able to laugh in a similar way last spring. We have more in common than the store clerk and I do. John T. and I share race, status, and regional origin. We are close to the same age. We are sons of the South. We’re both writers, married with families. John T. and I have cooked for each other, gotten drunk together, and told each other stories. We live in the same town, have the same friends.

But none of that mattered in the face of social class, an invisible and permanent division. It’s the boundary John T. had the courage to ask me to write about. The boundary that made me lie about the secondhand store last spring. The boundary that still fills me with shame and anger. A boundary that only food can cross.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.