A Slender Wage

By Kevin Wilson

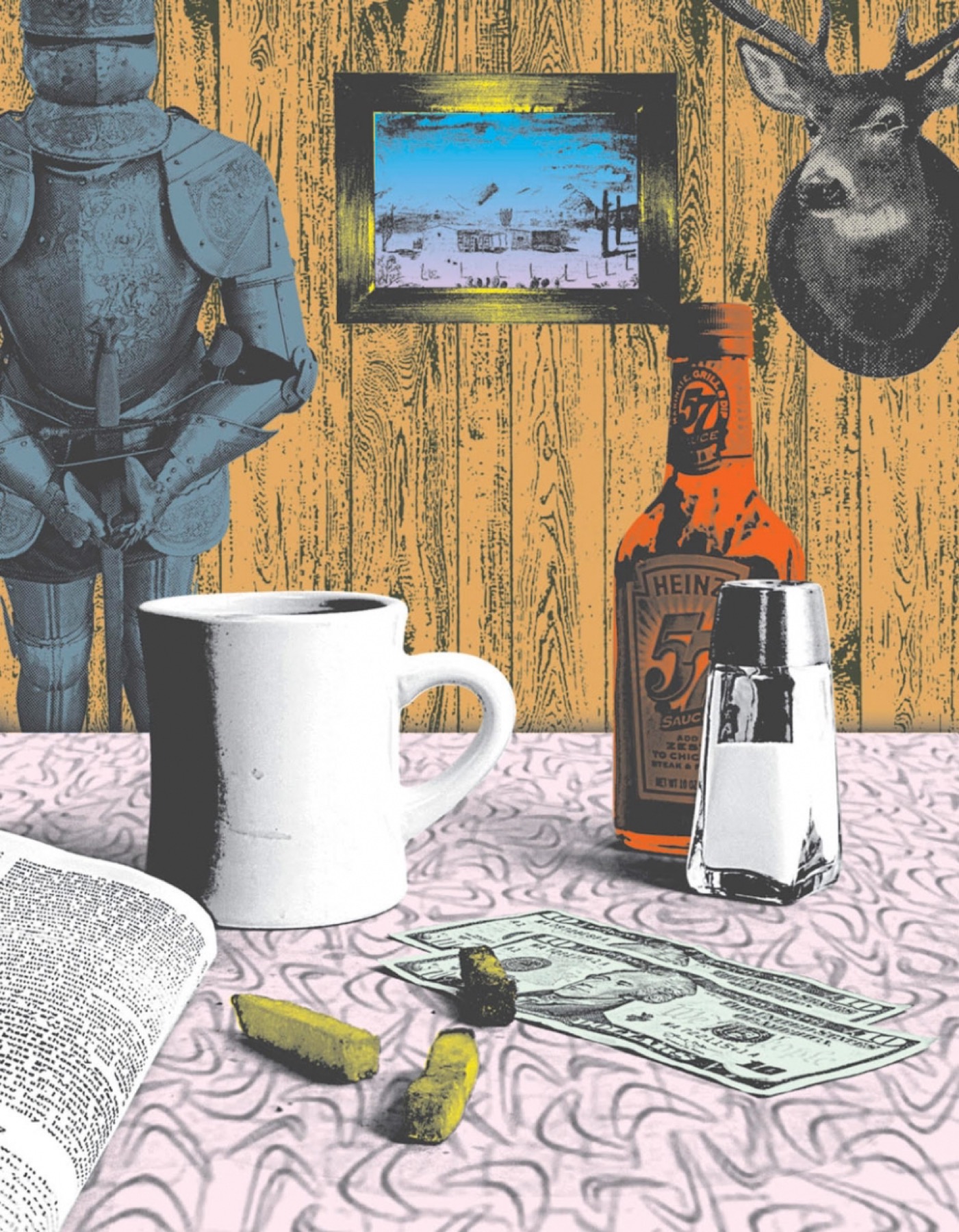

Illustration by Milton Carter

Scamp’s Diner was the kind of place that looked like the owners had run out of room to store their tin signs and stuffed deer heads in their own house and simply opened a restaurant just to house the stuff. There were four suits of armor awkwardly arranged between the booths and they all had index cards that said DO NOT DO NOT TOUCH!, and so nearly a full inch of dust had accumulated on them. When I first started working there, with no waitressing experience but nobody seemed to care, I noticed a tin sign for Luzianne coffee and chicory that had a mammy caricature, right above the window that separated the kitchen from the rest of the restaurant. I took it down, tossed it in the dumpster, and waited an entire week before I realized that no one had even noticed it was gone.

The owner, a woman in her seventies who made all the pies that we served (eight or nine varieties a day), would hang out on the second floor of the restaurant, where no one else ever went, even though there were tables and booths up there. She would read old copies of Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine and eat boatloads of french fries. When I went up there to get more bottles of ketchup or stacks of napkins, she would say, “I pay you a slender wage, because you also get tips, okay? Pretty girl like you, the tips come rolling in.” One time, I pointed at her mystery magazine and said, “I’m really a writer. That’s really what I am.” Like she hadn’t quite understood me, thought that I was waking up from a coma, she said, “You’re a waitress, okay? I pay you to be a waitress.” Only a slender wage, I wanted to say, but I was kind of afraid of her and I needed the job. Actually, I didn’t need it, could get another one pretty easy or just ask my parents to send money, but I liked to pretend that I needed it.

I told everyone, all the time, that I was a writer, because that’s what I’d majored in when I was in college, three years earlier, even though I still hadn’t finished any of the nine stories that I’d started since graduating. Even though my own mentor in college, a young woman who had published a critically acclaimed collection of stories, told me that sometimes my enthusiasm got in the way of my writing, made it clumsy. All I heard was “enthusiasm” and I just kept moving forward, toward my future.

The job was easy because Scamp’s business model didn’t really focus on new customers or making things easy for them if they found the place. We had regulars, good regulars, and they liked their meals a certain way, overcooked and a lot of it, and so they were more patient with me, even during the lunch rush, because they knew what they were getting. I poured coffee like a robot made just for pouring coffee, and once I memorized everyone’s usual order, they liked me just fine. I got tips, not enough to make up for the slender wage, but enough that I felt like money came easy to me.

There was a man, Walter Ronge, who was the branch manager at the First Volunteer Bank right across the street. He’d come in each morning to get coffee, which I poured directly into his thermos, and he’d take that to work. Then, at 1:30 P.M., once the lunch rush had died down, he’d come in again and order a hamburger steak and french fries. He was maybe in his forties, but youthful-looking, pale skin and blond hair. He wore these ill-fitting suits that looked like a tiny spark would make them burn up like flash paper. He was thin, but with really wide hips so he had to kind of slide into his booth in an awkward way. For a while, we barely even spoke to each other. He would bring that week’s copy of the New Yorker with him at lunch and read it while he ate. I would bring him Heinz 57 and refill his coffee and he would spend a full hour in that booth, quiet and seemingly happy. When the meal was over and I brought him his check, nine dollars and fifty-seven cents, he would put down two crisp ten-dollar bills.

The first time, after about two weeks, I thought it was a mistake, as he’d been leaving regular fifteen-percent tips, but he said, “The second ten is for you,” even though he still wanted his forty-three cents back on the actual check. I understood that he had a crush on me, because there is no service that deserves a greater-than-one-hundred-percent gratuity, but the money seemed harmless when it came out of his wallet, like something he’d found and was simply leaving for me to deal with. And after a month of this, I realized that I was making fifty extra dollars a week because of this man. I wasn’t attracted to him, but I was fond of him, I guess because he gave me fifty dollars a week for remembering that he liked Heinz 57.

I asked the only other server, the owner’s grandson, who mostly just worked the register, if he knew anything about the man, and he said he was some kind of big shot at the bank. But the First Volunteer was dinky even by the standards of this town. Everybody I knew, including me, banked at the Regions next to the Kroger. “But what’s his story?” I asked him, and he just looked annoyed with me.

“I don’t know,” he said.

“You don’t know anything about some big shot who comes here twice a day, every single day?” I asked. Other people, I lamented, didn’t care about stories, had no curiosity.

“I do not know,” he said, enunciating every word, “and I do not care.” When he could see that this did not satisfy me, he continued, “Walter Ronge and I do not run in the same social circles, okay?” I thought about this for a second. Walter Ronge was the only man in a suit who had come into Scamp’s since I’d been working there. I don’t think anyone else from the bank had stepped foot in the diner, which was maybe why Walter Ronge came here. The regulars, taxidermy enthusiasts who wore stiff jeans and work boots, simply ignored him. I now decided that he had come from humble roots, and no matter how many ill-fitting suits he bought, he was still a Scamp’s Diner kind of man. This was good. I could work with this.

“Did he ever leave big tips for the last waitress?” I asked him. “Not that I know of,” he said, and then he squinted at me. “Now, I think we should be pooling our tips together and splitting it, okay?” I laughed in his face. “No fucking way,” I said, and he just shrugged and went back to watching TV.

After a month of this new arrangement, all this money and still no invitation to fuck him or do weird stuff for him, I finally opened up, said the thing that I absolutely needed to say. I pointed to his copy of the New Yorker and said, “I’m a writer, actually.”

He looked at me like this was not silly. He turned to the table of contents and noted the story. It was by someone named Glennallen O’Rourke and it was called “The Morning Dew on the Sheep.”

“Oftentimes, if I’m being honest, the nonfiction is much better than the fiction,” he said, but he was smiling.

“I don’t read it,” I told him.

“Well, if you’re a writer, isn’t the New Yorker kind of the holy grail?” he asked me.

Was it? I wasn’t entirely sure. I hadn’t gotten to that point yet, needed to finish a story before I decided where to send it. “Like you say,” I finally told him, “it’s a little overrated. My work is a little more difficult, I think.” It was difficult, I was certain of that, which was why it was so hard to finish. The stories I wrote were about children who find a dead cat and keep it hidden in their closet or about a grandmother who starts turning into an elephant.

“Well, sometimes the fiction is really stunning. And even so,” he said, “it’s good practice, being a literary citizen.” It was a Friday, the last day of our weekly interactions, and he handed me the magazine. “You can have this. I’ll give them to you at the end of the week.”

I looked at the little white subscription sticker at the edge of the magazine. “Walter Ronge,” I said aloud. He had an address in a really nice part of town.

“People call me Rongo,” he said, but I knew that I could not call him that, not with a straight face.

“Ronge,” I said. “Is that German?”

“French,” he said. “It means to chew or something like that.”

“My name is Millie,” I told him. “Millie Moser.”

“I look forward to reading your book, Millie.”

I smiled, and we just kind of stood there. He then slowly reached for the check that I was still holding and slid it out of my grip. He put down two ten-dollar bills, and I took the bills, the check, and the magazine, and returned to his table with his forty-three cents, which he jangled in his open palm.

This went on for a few months, and it was such a lovely routine, so much so that what I had assumed would be a brief detour from my regular life started to seem quite nice in its own right. I’d waitress, and then I’d go back to the apartment I shared with a woman who worked as a secretary at a seemingly crooked law office, and I’d work on one of my nine stories, writing and rewriting a scene in which the main character finds a candy bar in the trash and it reminds her of her old babysitter, who turned out to be an arsonist. The stories never quite adhered—I could feel myself running about five steps too far ahead of them and then lost the thread—but it was wonderful to watch the words accumulate on the screen, to know that I was making something. In the bathtub, I’d read the story in that week’s New Yorker and, honestly, they were always really, really good. My professor had made us read Eudora Welty and Ernest Hemingway, but I didn’t really understand them, didn’t take the time to read them half the time. I wanted to write my own stories, not read other people’s. But now, on Friday nights, I’d sit in the tub, the water so hot it was barely tolerable, and I’d read about people with inner lives, with interiority, and they were doing interesting things. I could see it, could actually see the story in my mind. I worry that this makes me seem very stupid, that I was only now figuring this stuff out, but, whatever, maybe I was stupid.

After I finished the story, I’d flip through the issue and look at all the cartoons and imagine that the businessmen in them were Walter Ronge. I imagined him alone in his house, carefully counting out a stack of ten-dollar bills for the upcoming week. The steam from the tub made the little subscription sticker gradually pull away from the magazine and it floated on the surface of the water. I looked at his name, his address, until the ink ran and the paper disintegrated.

My roommate was convinced that Walter wanted to have sex with me. “If a guy just takes me to the movies and spends six bucks on a ticket, he is dead certain that this means he’s going to fuck me,” Jana told me. “This guy is giving you fifty bucks a week for refilling his coffee?”

“I don’t think he’s like that,” I told her.

“Is he gay?” she asked.

“I don’t think so. . . . I don’t really know.”

“He’s giving you all this money, Millie,” she said, stroking my arm. She was a few years older than me, wore her hair all teased up with hairspray, smoked menthols. She treated me like her stepdaughter. “It doesn’t make him a bad guy. I’m not saying he’s a creep. But he’s giving you money, and somewhere down the line, he’s going to want something for that.”

I liked looking in my pocketbook, all those crisp tens. I kind of tuned Jana out. She was used to dealing with defense attorneys who wore seersucker and talked about their erections in those weird, slow Southern accents. She was too jaded. It was just me and Walter Ronge in Scamp’s, well-done hamburger steak, short stories about very tasteful affairs.

“Could I ever read one of your stories?” Walter asked me after he’d finished his lunch. Now, before he even came to the diner, I’d have the forty-three cents out of the register and waiting in my apron.

“They’re not as good as the ones in there,” I said, pointing to his magazine.

“Can I tell you a secret?” he asked me, and I worried for only a second, and then I let him tell me, nodding for him to continue. “I actually wrote a novel.”

“You’re a writer, too?” I asked him.

“Not really,” he admitted. “It was a spy novel, not very good. I didn’t try to publish it or anything. I knew it wasn’t good enough for anything like that. But I did like the feeling of it, going to my computer every night after dinner and working on it, thinking about it.”

“What was the spy’s name?” I asked, and he immediately blushed.

“Walter Ronge,” he said, almost a whisper.

“I can let you read one of my stories, I guess,” I told him.

“I’d like that, Millie,” he said. He paid his check, left his tip, and walked across the street to the bank. I watched him through the window. I wasn’t sure if I was falling in love with him or what was happening. I hadn’t had a boyfriend since I’d moved to town, and I hadn’t been interested in it. I was the kind of person who liked living inside my head. I didn’t enjoy relationships, didn’t like the expectations that came with having another person know things about me. But I thought about Walter, his weird pear shape, and his cheap suits that accentuated that shape in all the wrong ways. I wiped down the tables and refilled the salt shakers. I ate a piece of chess pie. I imagined the subscription sticker on the New Yorker and it read: “Walter and Millie Ronge,” and it looked so silly and unbelievable that I felt like I could go on with my day.

“I liked your story very much,” he said the day after I’d given him the first twenty pages of an unfinished story about a waitress who makes black market fireworks in her basement.

“It’s not finished,” I told him.

“I know,” he said, “and I’m definitely curious to see how it ends.”

“I think maybe the fireworks will go off accidentally in her basement and it’ll kill her,” I told him, and he said that he’d suspected that might be the eventual outcome. Hearing how easily he’d expected that ending, I then said, “But I might not do that.”

“Well, I hope you’ll let me read it when it is finished. Or maybe I’ll read it when it’s published in the New Yorker.”

“No way,” I said, smiling.

Later, after I’d brought him his food and refilled his coffee, I went back to his booth and said, “I’d like to read your spy novel.”

He laughed, the first time I’d ever heard him laugh. It was crackly and weird. “Oh, I threw it away.”

“What?” I asked.

“I deleted it off my computer, and I threw away the only hard copy. I was embarrassed.”

“Even if something is bad, you should keep it,” I said, and it sounded so wise that I felt like a real waitress, like someone in a sitcom.

“Maybe I’ll try to write a short story,” he mused. “I’ve read enough of them by now. Maybe I could do it.”

“Well, if you ever write one, you should let me read it,” I told him.

When I talked to my mom on the phone, which we did every few months or so, just so we knew that the other was alive and well, she asked if I was seeing anyone.

“Kind of,” I said. “It’s still early. But he’s nice.”

“You deserve someone nice,” she told me.

One afternoon, Walter Ronge didn’t show up at the diner at 1:30. I’d filled his thermos that morning, the usual pleasantries. I went to the window and watched for activity at the bank. There was no sign of him. I thought maybe he’d gone home early because he wasn’t feeling well. Or maybe he was at the dentist’s.

Finally, at 3:45, he showed up, looking pale and sweaty. I smiled when he walked in, but he didn’t even seem to notice me. He just kind of waddled over to his booth and fell into the seat.

“I was wondering where you were,” I said.

“What?” he said, distracted. “Oh, yes, long meeting. A long, boring meeting.”

“I’ll get your food,” I told him.

“Actually, I just want pie,” he said. “Maybe two pieces of pie.”

“Really?”

“Two pieces of chocolate silk pie,” he said, not even looking at me.

“You didn’t bring the New Yorker,” I said, but he didn’t respond, just looked at his hands, which were shaking.

When I brought him the pie, he asked if I would sit with him and eat one of the pieces. I felt weird, like I had a terminal illness and the whole town had determined that Walter Ronge should be the one to tell me. But I sat down on the opposite side of the booth, which made the owner’s grandson raise his eyebrows at me.

I started eating the pie, but Walter wouldn’t even pick up his fork.

“I have to tell you something, Millie,” he finally said.

“What is it?” I asked.

“I am not going to be able to leave you the usual tip,” he said, and he looked like he was going to cry.

“That’s okay,” I said, though, actually, in the worst part of myself, I was more upset about this than I cared to admit.

“I lost my job today,” he said, and now he actually did start crying. I didn’t touch him; I just sat there and simply watched him. It was interesting to watch him cry. His face scrunched up, got real red, and a stream of tears poured out of his eyes for about two seconds, and then his face went back to normal and it was like he’d never even been sad.

“I’m so sorry,” I finally told him.

“No loyalty anymore,” he said. “You start making too much money and they decide that they can just find someone else to do your job for half the salary.”

“That’s not right,” I said.

“I won’t be coming in here anymore,” he said. “But I wanted to say that I’ve enjoyed our talks. I think you are a fine writer. And I hope things work out for you.”

Without even waiting for my response, he stood up, banging the shit out of the table with his hip, which made him wince. He walked out of the diner, and I just sat there. After a few seconds, I ate his untouched piece of pie because I didn’t know what else to do. I took the two empty plates back to the kitchen and dumped them in a sink full of hot water. I realized that Walter Ronge hadn’t even paid for the pie. He had been upset of course, had been so embarrassed about his firing that he’d forgotten about it. I thought that maybe the next day, he would come back into the diner, and he’d give me the money, plus a tip, and I’d put the money in my apron and I’d give him a hug.

Istayed up all night and worked on the story about the waitress. It wasn’t that I knew how it would end all of a sudden; I just knew that I needed to finish something, anything. I wrote and then rewrote, and then wrote again. I got the waitress out of that basement, away from all that gunpowder. I got her in some night classes at the community college, public speaking and world literature. I got her to the Fourth of July, sitting on a picnic blanket with some guy she’d met in class, and they watched these fireworks, admittedly not as garish and powerful as the ones that she made, and she was happy. I had always imagined that when I actually finished a story, I would write in capital letters, the end. But when I finished this particular story, I knew I didn’t need to do it. I knew that the story, that echo right after the last line, was enough so that anyone who read it would know that it was over.

I printed it off on my crappy printer, which seemed to take forever. I stapled it together. “Good luck,” Jana said, trying to be supportive. When Walter still hadn’t put the moves on me, she’d kind of lost interest in the whole thing, but she liked me, wanted me to be happy. I grabbed a copy of the New Yorker, with Walter Ronge’s address on it, and I got into my car and drove to his house so that he could be the first person to read my story. I imagined sitting on his sofa, watching him while he read each sentence, this happy ending that could be his own happy ending if he wanted it.

When I pulled into his driveway, I noticed that the yard was perfectly maintained, the lawn so manicured that it looked fake. The house was two stories, every single light on. I thought I could hear classical music coming from the house when I walked to the front door. I rang the doorbell, and after some shuffling, the sound of a dog barking, a woman opened the door.

“You have to be fucking kidding me,” she said, looking at me. Then she shut the door, and I heard her shout, “Walter! Walter, there is a woman at our front door.” Then she opened the door, and she said, “Who are you?”

“I’m Millie,” I said, but she made this kind of face that said, AND? and so I said, “I work at Scamp’s Diner.”

“What are you doing here?” she asked.

I was holding my story, which looked so silly now. Did Walter Ronge wear a wedding ring? I realized now that I’d never noticed one way or the other. I’d never thought to even check. I was a bad writer, I realized, the way I never noticed things that a writer needs to notice in order to tell a good story.

Before I could answer, Walter came running into the hallway, looking so sheepish that I wanted to start crying.

“Millie?” he asked, clearly confused.

“I finished my story,” I said, holding it out to him. With his wife watching him, fuming, he took it. “Thank you,” he said. “I look forward to reading it.”

“You edit their writing?” his wife asked him.

“No, Emily,” he said, anger in his voice. “Please—”

“Do you know that he was fired today?” she asked me.

“Yes,” I said.

“Because he was sleeping with one of the tellers?”

“No,” I admitted.

“Because he got her pregnant, and she told the regional manager about it? And so now he’s fired? And he’s going to have to support this woman’s child because she wants to have the baby? And that we have two daughters upstairs who are crying their eyes out?”

“No,” I said, feeling like I was three years old, being lectured by a nurse because I drank an entire bottle of dish soap.

“Emily, please,” he said to his wife. “Millie and I are friends. That’s all.”

“Just friends,” I said.

“And nothing more,” he said, which made my stomach hurt, like someone had kicked me.

And I don’t know why I was angry; actually, I know why I was angry. He hadn’t chosen me, maybe hadn’t even thought of me in that context, but I couldn’t quite figure out the depth of that anger, what it meant. Whatever it was, I felt like the thing that I cared about, that I thought Walter Ronge cared about, had just caught on fire. Or maybe had never existed. I wondered if Walter had even read the first half of my story.

“He gave me money,” I finally said, and I could see Walter’s expression crumble a little.

“Oh, is that so?” his wife said, now turning to Walter. She pressed her palms together and rested the tips of her fingers against her chin, like she was imagining what the next five, ten, fifteen years of her life would look like. She seemed to have trouble imagining Walter in any of those timelines.

“I thought he loved me,” I told her.

“Millie,” he said, so pale, just this dumpy little vampire, “things are complicated right now.”

“I really did,” I said, just to Walter, like his wife wasn’t right there. I still wasn’t sure what was going to happen. Walter looked like he was going to say something, but he just stood there, his mouth open, nothing coming out.

“I’ll never leave him, that’s the weird thing,” his wife finally said, which made Walter moan, this soft sound, and she ran up the stairs and disappeared.

And then Walter Ronge walked outside and shut the door behind him. It was just the two of us now, just standing there.

“I’m sorry,” he finally said.

“I don’t exactly know what you’re sorry about,” I admitted, and this made him smile.

“Everything,” he said.

“Well, okay,” I replied.

“I really do want to read your story,” he said. “I really do think that you’re a good writer.”

“I think I kind of don’t want you to read it now,” I admitted. I reached out for it and took it back, and Walter Ronge let me, as if this was exactly the kind of punishment that he could handle.

“Maybe . . . ” he said, trailing off. I realized that I’d never kissed this man. I hadn’t even shaken his hand, had I? And yet I felt so bad about things. I felt so bad that he was a bad person.

“Maybe,” he tried again, “this will make for a good story one day. Maybe you’ll write about this and it will be in the New Yorker.”

“And then you’ll read it?” I asked.

“I suppose so,” he said.

“I’m never going to write about this,” I told him, getting angry. “I will never, ever, write about this.”

“I’m sorry, Millie,” he said.

“It’s a bad story,” I told him. “It’s a really bad story.”

When I got home, Jana was painting her nails, drinking a White Russian. “Did he like the story?” she asked, which made me cry, this ugly, hiccupping, nose-running kind of breakdown.

“He didn’t like the story?” Jana asked, completely dumbfounded, not able to touch me because her nails weren’t dry yet.

When I still didn’t stop crying, Jana knelt down next to me. “Honey?” she said. “Do you think maybe you should leave this town? Do you think you should do something else with your life?”

“Where would I go?” I finally wailed, which was so embarrassing. This town meant nothing to me. It would be so easy to leave. I’d move to a city. I’d get an MFA. I’d date a boy who wrote formal poetry. But right then, on the floor, Walter Ronge my one true love, I couldn’t figure out what came next.

“Do you want me to read the story?” Jana finally asked, which was just about the nicest thing that anyone had ever said to me.

“No,” I replied, starting to calm down. “You don’t have to do that.” She looked so relieved.

“You are a good person, Millie,” Jana said to me, and it sounded like she kind of pitied me for it.

“I don’t know what I’m doing,” I said. “I don’t know what to do.”

“What do you want to do?” she asked.

“I kind of want to send this story to the New Yorker,” I finally admitted, sniffling.

“Well,” Jana said, no real idea of what I was talking about, “go and do that.” She helped me stand up and gave me a hug, her hands dramatically avoiding my hair.

“Were you like this when you were my age?” I asked her, and she emphatically shook her head and went back to the couch to keep drinking.

Back in my room, I put the story on my desk. I wouldn’t send it just yet. Instead, I thought about this new story that I was living, what it would look like, how it would go. I was a writer. I knew that I was. And someday I’d get other people to believe it. What I needed to figure out, what still wasn’t clear to me, was where one story ended and the other began, where you cut it off, where you said, in big bold letters, the end. I didn’t know that yet. But someday I would.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.