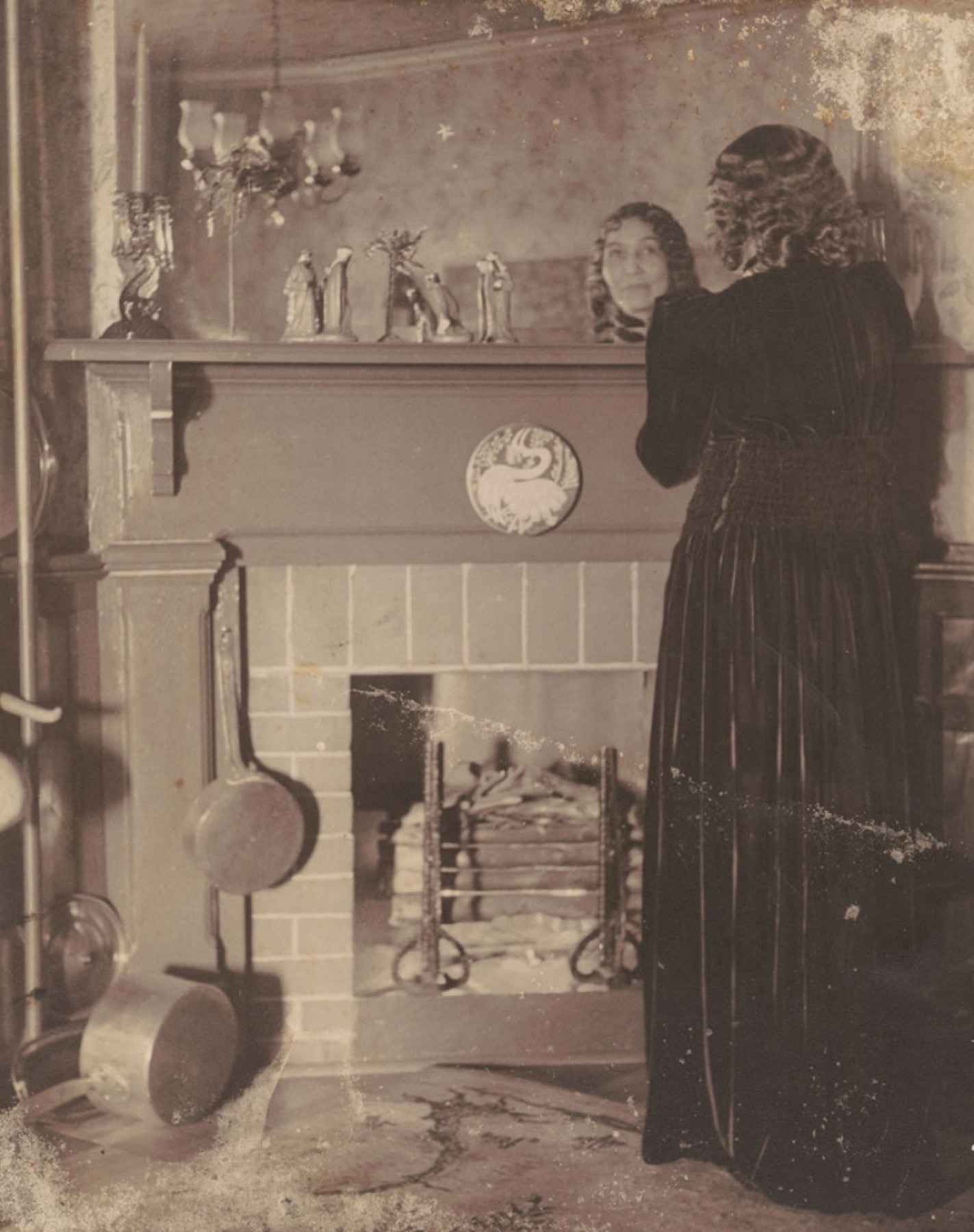

Photograph of Anne Spencer courtesy of The Anne Spencer Memorial Foundation, Inc. and the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia

Light the Word

By Tess Taylor

Anne Spencer’s ecosystem of art and activism

A

few years back, in the waning light of a brisk Virginia fall day, I stood in the poet Anne Spencer’s home, a marvelous house museum tucked into a quiet residential neighborhood. A few blocks away, the bald hills of industrial Lynchburg glittered with cars and asphalt. But the home—coolly elegant, alive with color—was a striking introduction to a remarkable woman. The entry foyer is pink. A lemon-yellow ottoman waits in the bronze sitting room, which holds a weathered copy of The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois. A parlor table holds papers documenting the initial meeting of the Lynchburg Chapter of the NAACP, convened here in 1917. The dining room is hung with a striking painting by Lawrence A. Jones, a Black Arts Movement painter, and the table is set with turquoise china. A bright, book-filled back room overlooks the garden, where a small cottage waits. The garden fends off the world’s turbulence.

The house I was discovering is at once stately, whimsical, and craftsy. In the kitchen (mint-green walls, deep-red linoleum floors, a splash of lime trim), a cupboard is hand-painted with a shortened version of Spencer’s 1926 poem “Lines to a Nasturtium.” In red, the text reads:

Day-torch, Flame-flower, cool-hot Beauty,

I cannot see, I cannot hear your flutey;

Voice lure your loving swain,

But I know one other to whom you are in beauty

Born in vain . . .

Yet here, nothing seems born in vain. Much is made out of tender and artful salvage. In the dining room, a painting on a copper plate echoes copper moldings. The kitchen has padded leather doors reclaimed from a movie theater. A French door is installed sideways above the cabinets, making the ceiling seem surprisingly airy. In some mystery, this vibrant cacophony is also sublimely still.

This house’s story, like Anne Spencer’s, is rich.

In a way, my first pilgrimage to Spencer’s home three years ago was an accident; in another way, I’d been led to Spencer by poetry. My family has roots in Virginia. My father grew up in Danville, just a stone’s throw south of Lynchburg, and I still have family in Richmond. In 2013, I published a book of poems about being a white descendant of Thomas Jefferson, and about attempting to reckon with my own Southern legacies. The question driving that book was about which part of my family history—or any history, really—gets saved, and why. I was aware of the deep flaws and violent omissions in historic archives, in which enslaved people’s lives are absent—actively suppressed, denied by law, and written down only through white people’s happenstance.

For me, a large part of my own reckoning has meant rebuilding my knowledge of the wider spread of my family history—trying to find what has been left out. Part of that has meant finding connections to my black cousins, and beginning to chart and meet and know family I didn’t grow up aware that I had. When I first visited Spencer’s house in 2015, I’d just been at nearby Randolph College talking with my cousin Gayle, who is African American, and descended as well from the white Taylor line. We were in Lynchburg discussing what we’ve learned by meeting, and what our shared history might help us all understand about how to connect in our still racially divided America.

Our host, historian John d’Entremont, had taken us through downtown Lynchburg, an old railroad and tobacco town perched on a steep hill above the James River. Like my grandfather’s Danville (or, perhaps more accurately, like most of America), Lynchburg has an uneasy and violent racial history. Lynchburg is a place where the pain of racism quite literally scars the ground. Even now, in the downtown park on Rivermont Avenue, a square grassy pit marks the footprint of the pool the city simply closed rather than desegregate. The flat patch waits, eerily silent amid the park’s hills. People call it the “dead pool” and its grassed-in rectangle serves as a de facto monument to the white town’s choice of division over integration—rather than providing more for everyone, there was less for us all. In the face of this history, it had not occurred to me that Lynchburg could be a hub for Harlem Renaissance poets. Yet only a few blocks away was an alternate history, hidden, as it were, in plain sight. Nearly a hundred years ago, a fascinating poet had hosted star-studded interracial literary salons, right in the middle of a garden that is still in bloom four decades after her death. Here was a different ecosystem of joyful and vibrant resistance. Once I visited it, I was transfixed. I was eager to correct the omission in my own knowledge, to fill in the blanks in my archive. I wanted to know more.

I’d studied the Harlem Renaissance, and my own life threads through Southern Virginia. I could actually envision my grandparents crossing paths, at least in ghost time, with Spencer. My grandfather was a young boy attending the Virginia Episcopal School in Lynchburg while Spencer was writing and working in the Jim Crow–era black library across town. Later my grandmother was also an active and devoted gardener at her own small home in Danville, some seventy miles south. Still, before my visit in 2015, I’d never heard of her work. I thought my ignorance might be because I am white, but as I spoke with African-American colleagues, I realized I wasn’t alone: Ismail Muhammad, a critic and scholar working on James Weldon Johnson, Spencer’s mentor and patron and friend, had not heard of her. Neither had Tyehimba Jess or Kamilah Aisha Moon. Camille Dungy knew her work, but she has taught in Lynchburg. As had Kevin Young, though he is an archivist. Airea Dee Matthews had heard of her in passing. Greg Pardlo had heard of her through Camille.

A likely reason is that Spencer’s published output is small. Langston Hughes once said that “there is an unsharpened pencil on Anne Spencer’s table,” and indeed, when she died in 1975, she left a great deal of unfinished work, and only thirty published poems. Even though in 1973 she became—even before Gwendolyn Brooks—the first African-American woman to be featured in The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry, she’s sometimes overlooked in contemporary conversation. Spencer defies easy categories: She is referred to sometimes as a “Lynchburg-based Harlem Renaissance poet,” but this isn’t quite right, because while she hosted and befriended and was mentored by Harlem Renaissance writers (Hughes and Johnson, particularly), she did not access structures of white patronage, or New York editorial circles, or even Harlem itself. She spent very few years actively sending out her work.

Anne’s father, Joel Cephus Bannister, who was black, white, and Seminole, had been born into slavery in 1862, and after he married Scales, the two continued to live on the Virginia plantation where Anne was eventually born. Bannister later opened a bar in Martinsville, Virginia—an entrepreneurial job that he preferred to any in which he would have had to answer directly to a white man. The marriage was uneasy: Scales did not approve of the customers of Bannister’s bar, but Bannister did not want his wife to have to work for white people. Money was tight. Spencer’s parents separated. Although she and her father corresponded, Anne never saw him again.

At the time, Anne’s mother left her, then six, with friends in Winston-Salem for nearly a year. Eventually Scales found work as a cook at the Blue Stone Inn in Bramwell, West Virginia, and then went to pick up her daughter. They had family working in the nearby mines. But because Scales worked in town, and because she preferred to have Anne associate with middle-class black families, she boarded Anne with the family of the local barber. In his biography, Time’s Unfading Garden: Anne Spencer’s Life and Poetry, Greene reports that Scales looked down on working-class black society, particularly the children of miners. In town, by contrast, Anne befriended a girl her age named Elsie. Elsie was white, but the town was small and the two were well matched in age and temper. People in town did not seem to object to their friendship, and the girls played freely and ate together at restaurants. For these formative years of her childhood, Spencer was spared some of the harshest violence of American segregation.

The Bramwell years were relatively happy, but Scales was hard-pressed to find adequate—or really any—local schools for her daughter. She did not want Anne to associate much with white people, and she also did not want her to attend the free black school with the children of black miners. Though he was by then living in the Midwest, Bannister wrote and demanded that Anne be sent to school. In 1893, on her hotel salary plus contributions from Bannister, Scales sent Spencer, then eleven, to Virginia Seminary in Lynchburg, one of the region’s best schools for blacks.

When Anne arrived in Lynchburg, she could barely read. Later, she recalled, “When I went to the Seminary, I could call all the words, but I couldn’t understand them all.” Nevertheless, she was diligent and ended her time at the school as one of her class’s highest achievers. In Lynchburg, she was also more fully exposed to various forms of American racism, even on the grounds of the school. The new school was ambitious but also deeply underfunded. Food was so scarce that Anne came home one summer malnourished. She was able to study French, German, and Latin, but the school’s white funders were also suspicious of educating blacks outside the trades. These supporters preferred that students be taught sewing, and Spencer later remembered that when white patrons arrived, her teachers would rush to bring out sewing machines and ironing boards. At one point, when a white leader of the National Baptist Convention discovered that the students were being taught Greek, he rescinded his annual donation of $1,000, which had supplemented the headmaster’s salary.

Yet Spencer was learning not only Greek but French and Latin, reading Kant, and studying Emerson. Her teachers, often highly educated blacks who had come from the North to work, were deeply inspiring to her. At school, Anne (still calling herself Annie Scales) met Edward Spencer, a generous young man known for helping out with chores. He tutored her in geometry in exchange for her help with language translations. The two fell in love.

About that time she began writing poems. She also gave her high school’s commencement speech, using de Tocqueville’s ideas to suggest the role of black citizens in revolutionizing America’s future. Later, she remembered it as an optimistic moment, and that her speech was well received by both whites and blacks in the audience. Optimism or no, Anne was poised to enter a violent, deeply segregated world.

About her life, Spencer wrote, “You see, no dream can live unless somebody lets it live or die unless somebody kills it. 25 years ago I drew from the lottery of matrimony its greatest prize, an understanding heart.” Her marriage was happy, supportive, and fortuitous. Together, Edward and Anne built ecosystems for art, activism, family, and retreat. They worked to achieve a kind of middle-class black life that had been unavailable to their parents, and certainly to their grandparents. Edward Spencer worked on the railroads; bought, sold, and developed properties; and owned a neighborhood grocery store. By 1910 he had a post office job, one of the first stable government jobs open to blacks. Meanwhile, he was a builder. He had an eye for salvage, and he slowly tinkered with the Pierce Street home. Anne later recalled, “He was always picking up trash and making it look like . . . Lloyd’s of London.” Of the careful additions they made to house and garden, she wrote, “We have a lovely home—one that money did not buy . . . it was born and evolved slowly out of our passionate poverty.”

Anne had, for a mother of three, and for a black Southern woman of the 1910s and ’20s, a rather radical freedom to write. The family hired help with laundry, child-raising, and cooking. Edward supported her ambitions. She often woke late, dressed slowly, and went to work in the garden, joining her family for dinner, and then staying up in her cottage in the garden with books and papers. Sometimes she drafted lines in the morning while getting dressed, then worked these lines into poems at night. This poem likely dates from that time, describing a washwoman that Spencer, in her notebook, called “a high priestess of cleanliness”:

Lady, Lady, I saw your hands,Twisted, awry, like crumpled roots,Bleached poor white in a sudsy tub,Wrinkled and drawn from your rub-a-dub.Lady, Lady, I saw your heart,And altared there in its darksome placeWere the tongues of flame the ancients knew,Where the good God sits to spangle through.

The poem is at once domestic and intimate. It looks at and also through the mangled body to the place where the heart becomes an altar for the tongues of flame that are also glimmerings and flickerings of God. It is a poem about work and about immanence, and it flares out in a spangling of recognition and praise. Meanwhile, without any explicit racialization, the poem subtly inverts a clichéd reading of color in which white is valorized and darkness denigrated. In this poem, “poor white” is the result of a wound of bleaching, and the darksome inner heart is the place of an altar. It’s a move that freshens the poem, and offers a counterpoint to the readings most often offered by the world.

In its compassion for the twisted domestic body, it recalls other lines by Spencer, in particular an untitled poem which begins “Thou art come to us, O God this year,” and goes on to describe the arrival of God in the form of wisteria blossoms. That poem ends:

We thank Thee great God—We who must now ever houseIn the body-cramped places age hasdoomed—That to us comes Even the sweet pangsOf the Soul’s illimitable sentienceSeeing the wisteria Thou has bloomed!

These lines are housed in the garden, along the paths of a “body-cramped” daily life. In this poem, as in others, the very act of reaching out toward beauty brings us “pangs” of sentience. Spencer’s poems build altars that are housed in the broken, even doomed world.

As Spencer puts it in another poem: “God speaks, and being comes to ardent things.”

We do not know much about when in Spencer’s life these poems were written. Yet we do know something about Spencer’s life in the “body-cramped space” of the segregated South, and the necessary labors she also undertook to build gardens of all kinds within it. When I talked to Camille Dungy about Spencer recently, we found ourselves talking about how busy Spencer had been—on her land and in her community. Much of Spencer’s life beyond the page was devoted to the hard work of building an environment in which her family, and her community, could thrive. In fact, her entire publishing career grew out of a meeting that was both chance and deliberate action. The NAACP had been founded in New York in 1909 in response to a series of particularly horrific race riots in Springfield, Illinois, to address the ongoing violence of lynching. By 1917, James Weldon Johnson, a field officer whose job was both to start new chapters and to investigate lynchings, was sent to Lynchburg. The Spencers were asked to put him up. Anne almost said no—Edward was sick—but hosting Johnson turned out to be a life-changing event. He stayed for several days and returned frequently after that, and the two became fast friends. Johnson saw Spencer’s poems lying around the house. He offered to take them north and show them around. Later, Spencer recalled how “James Weldon Johnson, by an act of god, [came] my way [and] sent a piece to Mr. Mencken. Mr. Mencken said it’s OK to print.”

Suddenly, in her late thirties, with her three children nearly grown, Spencer was given a line of contact to black intellectual life outside Lynchburg. H. L. Mencken did read the poems Johnson sent him, advising him to tell that woman to put “beginnings and ends on her poems, I can’t make heads or tails of them, but they’re good.” Spencer for her part was happy enough to be introduced to Mencken but reluctant to change her poems to please him. She had been writing for herself long enough by then that the words of a white New York editor did not necessarily seem useful. Yet Johnson was excited by Spencer’s work and was able to include it in The Crisis, the journal of the NAACP. “Mr. Johnson himself found me,” Spencer wrote later. “He came walking through our woods one day and picked me up. A risky thing to do. My tastes are likely considered plebian by many ‘best peoples.’”

Yet the poems caught great local attention. Alain Locke, known as “the father of the Harlem Renaissance,” included the washerwoman poem, “Lady Lady,” in his groundbreaking collection, The New Negro. By 1926, at the suggestion of Louis Untermeyer, she was sending poems to Countee Cullen. In 1927, Alice Dunbar-Nelson praised her as “Anne Spencer of the unforgettable line, cool, aloof, dispassionate, immortalizing the diving girl at the street carnival.” W. E. B. Du Bois wrote, asking her for poems. It is hard to know what Spencer would have made of a note about her work from Mencken to Johnson: “This is very curious stuff indeed,” Mencken writes. “For the very first time, in a poem by an American colored poet, I get an echo of what seems to me a genuinely African note, or in all events, a note not western and Anglo-Saxon. The faults of the thing are obvious. Its rhythms are a bit harsh . . . if it were not so long I’d be tempted to print it.” One can easily imagine why pleasing Mencken might have left Spencer uneasy. Indeed, Spencer disliked what she later called the “Tom-tom forced into poetry,” and she was also cautious of having to perform blackness for white editors, or change her poems to satisfy their ideas of blackness. Dungy also points out that Spencer may not have always wanted to fight the uphill battle of proving herself to the era’s tastemakers—whether they were the black men of the Harlem Renaissance, or white New York patrons and editors. That she was writing about topics that were perceived to be feminine or domestic may also have affected how she was received by a male, urban, Northern audience. “The fact that she was a black woman living in the South diminished her relevance to the tastemakers of the time,” Dungy said. As Greene notes in his biography, “In many ways the Harlem Renaissance was white, as well as it was black.” Spencer did not have, or seek, a white patron.

Yet even while her visitors came from far and wide, Spencer admitted that in her hometown, she did not feel free to travel in public. She did not like going to any side of town where she might incur racial slurs. She did not like riding Jim Crow public transportation. She had attained a degree of freedom to pursue her art. Yet this freedom had painful margins. As she wrote, “We do not go to the Jim Crow galleries or scenario houses—we stay away and read. I read garden and seed catalogs, Browning, Housman, Whitman, Saturday evening post, Detective Tales, Atlantic Monthly, American Mercury, Crisis, Opportunity, Vanity Fair . . . or anything. I can cook delicious things to eat.”

However, of necessity—and because she was an activist—Spencer did leave her home circle. She took a job to help send her children north to college, working for some time, as she put it, “in the Jim Crow library”—the only black woman employed by the all-white Jones Library in Lynchburg. (With no library training, she got the job after showing the librarian her published poems.) She pushed for the library to desegregate, but this idea did not take. In 1924, Spencer was granted the role of head librarian of a new black library. This turned out to be an empty, bookless room in Dunbar High School, to which she donated her own books for the rest of her career. Spencer worked as the librarian at Dunbar for twenty-one years. Her pay was $75 a month.

Spencer was also an activist in her daily practice. She often walked miles to work to avoid riding segregated public transportation, and, when she did ride, she was known for chewing out the bus drivers who told her to go to the back of the bus, and for marching into the offices of the bus company to advocate and complain. Years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Spencer once simply got tired and sat down.

After the publication of her poems during the Harlem Renaissance, Anne Spencer largely ceased sending out work. She remained friends with Hughes and spoke of writing an eerily prescient novel in which a white man goes around passing for a black one, a premise that remains hauntingly fascinating now. (The white novelist Jess Row published an acclaimed novel on racial reassignment in 2014, and at a recent talk, Zadie Smith discussed the voyeuristic pleasures of creating a white man as her protagonist.) I can well imagine Spencer feeling keenly aware of the lie of race and the absurdity of being forced to live in a racialized body; of the strange unaccountable violence of having to pass one’s life in a body whose freedoms are curtailed for no valid reason.

Spencer’s novel has never been found. Johnson—who remained a dear friend—died in a car accident in Wiscasset, Maine, in 1938, and when he did, Spencer lost an important advocate in New York. In 1947, she sent the bulk of her correspondence with Johnson to the Yale library, where it is now housed. Late in his life, Hughes wrote to let Spencer know he had anthologized her work as far as Argentina, and had listed her in a newspaper article titled “famous Negro women of History,” next to Gwendolyn Brooks. In an undated letter—the handwriting suggests it’s from closer to the end of her life than the beginning—she coolly answered a correspondent: “I do not send my poems out; however, you may use the ones you mentioned.” In another undated fragment, she writes that she’s not certain that “the scribbling I’ve always done would mean anything to anyone but my family.”

I do not know why she was unsure. It is true that Spencer was growing older, and she was also working full time. And it is clear that she was preoccupied with the welfare of both her family and the library, and with local and national civil rights struggles. It is possible that these concerns simply took up her time. Johnson once wrote that “the Negro in the United States is consuming all of his intellectual energy in this grueling race struggle.” This too is a possibility.

The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections in the Alderman Library at the University of Virginia is housed on the far side of campus, away from town and beyond Jefferson’s famous rotunda. In the rotunda, one ascends an oval staircase into a glowing room which feels like the scoured and idealized inside of an eighteenth-century skull, as if one has climbed into the great mind itself. In a clever architectural counterpoint, the UVA archive operates in reverse: to attain knowledge, you have to descend curved staircases into a dark hold below ground. There is a light well, casting a bright beam from aboveground over everything, echoing the rotunda’s light. But here everything is also crevicular, and buried. Everything must be exhumed and painstakingly pored over to find out anything at all. The silent room also seems to hum with thinking: People sit working out of dusty books and scouring old tomes to craft projects about the Atlantic slave trade, French Haiti, or colonial pirates. One has a feeling of history itself being made out of the tatters of wildly imperfect documents, and of the act of making knowledge as that of building a frail raft on a vast sea.

I’d last been to the UVA archive to work through the Randolph-Jefferson-Taylor papers—to look at the records of Randolph family violence and omission and willkeeping and property, and perhaps trace how to write my way through and also out of them. That had been a decade before. Now I was back to look at Spencer’s papers in all their tantalizing, disordered glory, to see what traces of her poems I might find. Unlike someone like Bishop, Heaney, or Hughes, it is not clear that Spencer crafted her life toward any archive. A great deal of the material is undated, which makes it hard to trace an arc, and yet, as in her house, the scribblings offer up a bright revelation into a life lived in courage and art.

Looking through the archive, I felt many quick tingles: There’s W. E. B. Du Bois’s calling card! Langston Hughes’s stationery! Other scraps are undated and barely legible. There are forays into a huge number of unfinished topics. Spencer wrote a long and presumably unsent letter to President Truman about her fury over Selma. She drafted lines on the back of mimeographed treatises which prepare to review the premises for “the existence of segregation in the Southern United States” and (correctly it seems) identified true “racial harmony” as America’s “supreme challenge.” There are drafts of letters to politicians full of pointed (and possibly unsent) fury. Other scraps are telling: On the back of the report of the Lynchburg Interracial Commission of 1961, she wrote: “The eye looks, but it is the mind that sees. This lack of synonymity between worlds resolves many reading dilemmas . . .” She added, tellingly: “For the one thing I cannot understand is poverty.”

Spencer’s family was a hub of pride and accomplishments; the letters also reveal children and grandchildren sending home news about civil rights marches, trips to see Dr. King, the integration of the New Jersey schools, organizing art shows in local libraries. In the early 1970s, her great-grandson Mark wrote her to seek “ideas about the future and direction of Black Literature.” ]

Amid the many fragments, tantalizing discoveries still wait. Although her notes are full of unfinished trails, some of Spencer’s scraps feel perhaps like Dickinson’s might have, but without the benefit of fascicles. A poem I liked—scrawled on brown paper—read as a modern blues:

A rosy moon hangs over Venice.

A gold moon hangs over Spain

But the blood from old Egypt

Hangs an orange moon for the slainA rosy moon hangs over Venice

A gold moon hangs over Spain

But an orange moon drips over Egypt

Gold red, blood of bleak hordes slain—

Another fragment, on an electric bill, reads:

These streets . . . are too expensive

In gold and milk pearlsnobody’s been to heaven

since reconstruction years

Sometimes, the notes and scraps are reflective. In a letter from 1926, Spencer writes, “Being a Negro woman is the world’s most exciting game of ‘Taboo.’ By hell there is nothing you can do that you want to do and by heaven you are going to do it anyhow.” About her own writing, Spencer wrote: “I write about some of the things I love. But I have no articulation for the things I hate.” And: “I just about told my truth about being a Negro woman. I like it. I revere America, but I revere the value more than its price.” And: “If I am sane at all the US of America is more than its parts, more than any people, any place: it is human destiny’s last chance.”

As I read, I fell in love with Spencer’s fierceness and wit. In some ways, she reminded me of my own grandmother—a voluble woman, gardener, and scrawler of notes on the back of lists. Finding Spencer’s scraps, I felt the same sort of matriarchal literary presence amid the dailiness of domestic life: glimpses of how an ambitious, literary-minded woman might manage a house. I admit—as a busy mother of two who often resorts to drafting on the back of shopping lists—that these images feel fortifying, even now. Spencer’s papers are full of terrific one-liners. One hauntingly beautiful fragment reads: “Things starkly different can equal—if love is stronger than death so is ignorance.” Another: “My favorite age for woman is when she has left giggles but come to laughter.” Another: “I like to think there exists but one kind of love and one kind of garden.” Or: “The soul has mostly conscience, the body mostly intellect.” Another: “Gardens are the best empiric symbols of their archetypes, the green places of the universal soul.”

I wished Spencer safety in her own body and in her own town. I wished her a school where no one ever had to put out an ironing board to justify or camouflage the life of her mind. And as someone who has wondered many times what it must have felt like to live through those years in Southern Virginia, I was grateful, through the notes, to be able to climb, for a moment, inside the vision of such a fascinating interlocutor; as if looking through her eyes helped me to see better the world I wished to know.

Anne Spencer’s garden, like her home, is carefully planned, full of color and whimsy. Foxgloves, peonies, and lilacs dance around a series of boxwood hedges. At the center of the garden a pergola painted robin’s egg blue is draped in grapevines, and in the back is an Arts and Crafts cottage, a cool shed with a desk and slanting light inside. Spencer called the garden her Gethsemane, referring to the garden where Jesus passed his final earthly hours: “We must trust in God,” she wrote. “To have faith in our best hours means nothing—it’s our own Gethsemane, too, that makes us believe truly in Him.” In the broken, body-cramped world, Spencer built a place in which to try to glimpse something much better.

After Spencer’s death, it is fitting that the garden became, in its own way, an emblem of reconciliation. When the garden fell into neglect in the early eighties, her son, Chauncey Spencer, asked the ladies of Lynchburg’s Hillside Garden Club to help restore it. At that time, the Garden Club’s ladies were all white. Most had never heard of Spencer, and few had ever visited the black side of town. Nevertheless, painstakingly, these women restored the garden to health, pruning back roses, nursing original bulbs. These days the garden is open from sunrise to sunset, seven days a week. The Hillside Garden Club maintains the garden for the public—and as a space to stop, and linger, and read a poem. Unlike the dead pool, the garden is alive. It is blooming.

Chauncey Spencer has passed on, but Shaun Hester, his daughter, recently moved back from Washington, D.C., and is restoring the house, room by room. She welcomes visitors by appointment, and many Sundays find her sitting in the garden. This spring, I noticed a portrait of a Reynolds patriarch on the wall. Shaun is not sure if it’s R.J. himself, but it was a gift from a member of the Reynolds family who had heard Spencer’s story. There are signs of quiet reconnection: Hester told me that she’s had lunch with members of the Reynolds family and presented some of Spencer’s work in the Reynoldses’ homestead.

We walked through the vermillion bedroom where James Weldon Johnson wrote, passing the canary cleaning nook, and made our way downstairs and out into the cottage in Spencer’s garden. We stood in the cool of the cottage, and I could imagine so much reading and thought taking place in this space, so many evening conversations between artists. “I sometimes wonder if they knew that they were making history or having such an impact on the world,” Hester told me. It’s hard to know what they knew, but we do know that a hundred years ago, they laid down a path for us. And Spencer’s life was part of making this new beauty possible, and the vision can now and again offer some hopeful and necessary balm.

It is exciting to uncover Spencer and begin to think about once again sharing her legacy with others. “I read Spencer as a contemporary sister voice,” said Camille Dungy when we discussed her this spring. “Her practice of being both an activist and a voice of rooted poetry feels so relevant and so contemporary. She was working at the intersection between environmental and civil justice.”

In 1972, in a rare dated note, Anne Spencer wrote, “Life requires more of us, its creatures, than we have to give, but accepts our median, and marks it paid in full.” In 1974, too old to garden, Spencer wrote this last poem from her sunporch:

Turn an earth clodPeel a shaley rockIn fondness molest a curly wormWhose familiar is everywhereKneelAnd the curly worm sentient nowWill light the word that tells the poet whata poem is

Sentient: the word comes back again. Coming to know, able to come to knowledge, alive, awake to the world and its possibilities. I think of this word, as well as the word “ardent,” as well as the word “being.” Each embeds within itself a kind of transitive hopefulness—a state not only of feeling, but of coming to feel; not only of burning, but coming to burn. There’s a hope in this tense of something proximate, quickening us, perhaps to arrive. It’s this state that Spencer seems to wish for each of us, her belated readers, to feel. In her poems, and now, in her garden (which is the alternate archive of her life), Spencer’s work seems to urge us to find the fondness of heart that unsettles us into blooming—toward the world, and maybe, at last, toward one another.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.