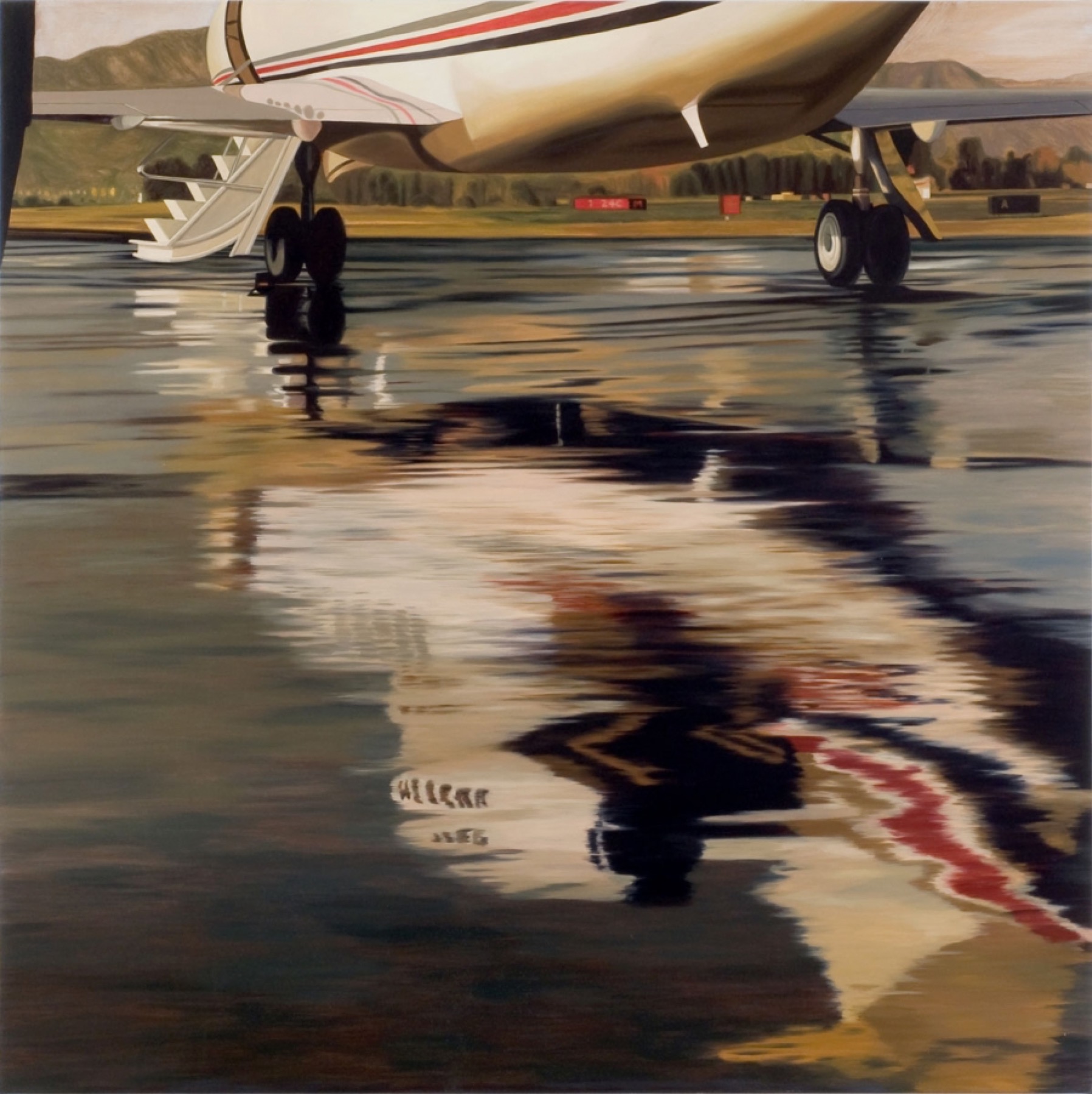

“Tarmac with Jet” (2008), by Julia Jacquette. Courtesy of the artist

Storage and Retrieval

By Becky Hagenston

J

anet was already three hours delayed when she heard her dead ex-husband being summoned over the courtesy phone at the Atlanta airport. He had left a personal item behind and could claim it at gate D44. Or perhaps she was having auditory hallucinations after three glasses of free Sky Club chardonnay. But no: there was the announcement again. Her dead ex-husband had left a personal item at gate D44. Well, of course it wasn’t him, just someone with the same name: Ronnie Rogers. Like a child in a cowboy movie. The marriage had lasted almost five years, almost two decades ago. By the time he was killed on the motorcycle he’d bought after the divorce, they hadn’t spoken in years.

Janet stuffed more popcorn into her mouth. On the barstools to her right, a couple in matching green sweaters was arguing over whether their cat could be safely left with someone named Taffy. To her left, a dreadlocked white guy poked at his phone.

“I wonder what that man left behind at gate D44,” she said to him. “What constitutes a personal item? Underpants?”

The man blinked at her. “That would be pretty personal,” he said. He had an accent she couldn’t quite place. She was aware of him regarding her with bemusement, the way most people did when they first saw her. She knew she resembled a twelve-year-old with an aging disease: slim hips, flat chest, curly auburn hair, reading glasses on a chain, and wrinkles. She bought her jeans from Target’s Juniors department. “You’re an odd sort of creature, looks-wise,” her last boyfriend had told her, just before breaking up with her, which was the same thing he told her just before hooking up with her.

“Where are you going?” she asked the dreadlocked guy. Wine made her nosy. “Where are you from?”

He gave her a steady, annoyed look. He was probably her own age, mid-forties. “I’m from Denver,” he said. “I’m going to Denver.”

“I’m a librarian,” she said. “I’m going to meet a robot.” This was true. The man smiled and turned away. She knew nothing about robots, which was why she had to go meet one in person. But would she ever get there? The couple beside her hauled their considerable asses off their stools. “Woohey, drunk,” said the woman. The announcement came again: Ronnie Rogers, where could you be? We need you here at gate D44, to claim your underpants, or your monogrammed toothbrush, or your phone with the contacts of all the people you ever loved or tried to love.

The Sky Club was at gate D27, and her flight from D13 was still delayed. Who was this Ronnie Rogers? Was he anything like her own? Maybe it was nostalgia that gripped her, maybe it was something else. She checked around herself to make sure she’d gathered all of her own personal items. “I’m off,” she said to the dreadlocked man. Off my rocker, off my ass, off my axis. He didn’t look up. “Going to look for my dead ex-husband.”

“Have a good trip,” the man said.

T

he robot Janet was going to meet lived in a research library in Michigan. As part of her new head-librarian duties, she had purchased a similar robot for her own research library near Atlanta, to be delivered next month. She just needed to learn how to operate the thing. It was a revolutionary way of storing and retrieving. No longer would students waste time browsing gold-embossed spines; no longer would couples, brains a-tingle, fall into scandalous embrace surrounded by musty, lusty volumes of medieval French literature. At least the study carrels could stay. It was the books that were on the way out—or rather, on the way to the library’s new climate-controlled wing, where they would be scanned and then stored according to size—size!—in bins stacked like tiny skyscrapers four stories tall.

In a YouTube video, a cheerful voiceover described how the new system stored books and journals in “one ninth the space needed for shelves, making room for more work stations, computers, and study areas.” The camera panned over an empty-looking room where multicultural students sat at round tables, smiling stiffly at each other.

The best part of the video was when the robot, a four-story-tall yellow crane that looked like a forklift combined with a dinosaur, raced along a track and pulled out a bookshelf-sized bin—so quick, so easy—and brought it, like a hurrying butler, to the work station where a human being plucked out the correct book to scan and send to the circulation desk. All in ten minutes or less from the time the smiling students clicked their request.

Sometimes, in her dreams, Janet saw the robot moving through her body: retrieving bones and cells and then re-storing them, traveling along the track of her spine from her brain to her belly. She saw the robot open a drawer and peer in, then close it and zoom away.

She hurried past the Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf, the Atlanta Daily World store, the Delta employees hawking American Express cards, and the people dressed in shorts for the Atlanta September or coats for the wintery place they were headed. She didn’t realize she’d been running until she stopped running. D44 was where the terminal terminated in a pod of gate areas and chairs and passengers sitting on the floor glaring at their laptops. Behind the gray-haired man standing at the D44 counter a sign said that Flight 4315 would be departing in an hour for a place Janet had never heard of.

Her own Ronnie had never been on an airplane. They’d met in high school in a bland suburb of Baltimore, Janet Rogers and Ronnie Rogers—how funny would it be if they got married? And they did get married, to their parents’ delight, when they were nineteen. Not just because they had the same last name but because she thought she was pregnant. He’d been a tall, laughing boy with thick dark hair, prone to practical jokes that often took a turn for the near-fatal (the wall of fire in the street; the sleeping pills in his mother’s martini). He was an Elvis fan, so they’d driven to Memphis for their honeymoon, toured Graceland, and stayed two nights at the Peabody, where they saw the ducks march from their penthouse elevator down a red carpet and plop, plop, plop into the lobby pond.

“Someday,” Ronnie had said, squeezing her close, “we’re gonna live like those ducks.”

She wasn’t pregnant after all. She finished her English degree and read novels out loud to Ronnie to help him sleep. He worked at a garage and came home smelling of gasoline and oil and sweat, and she loved him for this, and for his big, loud body and his big, stupid dreams. When she told him she’d been accepted to a master’s program in Alabama, he said, “Well, there’s no way I’m going to Alabama,” but she’d known that already, and known already that he was sleeping with the chirpy cashier at the garage, who smelled of jasmine.

She watched as the gray-haired Delta employee at the gate D44 counter picked up his phone. “Ronnie Rogers,” he said solemnly, as if issuing a call to prayer. “Please come to gate D44 to retrieve a personal item.”

How long would he keep doing this? At what point did he decide, Fuck it, Ronnie Rogers, your personal item goes to the land of lost personal items, never to be seen again?

And then Janet felt her breath stall in her throat as a tall man in a khaki windbreaker hurried to the counter and said something in a loud, laughing voice. It wasn’t exactly Ronnie, not quite; not the Ronnie she knew, but the Ronnie he might have turned into, forty-three years old, a little chubby, a little bald. The man behind the counter nodded and handed over a small orange case. It was shaped like a cube. It had a little handle. Ronnie Rogers took the case and hurried away, back up the corridor toward the other D gates and the C gates and the rest of the entire world, and Janet—slightly drunk, yes, and stunned, and delayed forever, it seemed—turned and followed.

The week before, she’d had a party at her house to celebrate the purchase of the robot, and her colleagues had gathered in Janet’s kitchen, eating Triscuits and brie, drinking beers and doing shots of Jägermeister because why the hell not? Janet showed everyone the YouTube videos of the robot doing its thing, and everyone said, Wow, we were expecting something cuter.

“Cuter, how?” Janet asked.

“With a personality at least,” said her friend Molly. Molly was director of acquisitions and six months away from retirement; she wasn’t keen on the idea of having to work with a robot. She’d been the one to catch her own graduate assistant stealing books and had reported him to Janet, who reported him to the dean, who had him arrested. “Maybe with a little face and little hands.”

Janet didn’t care that her robot had no face and no hands. It did what it was meant to do; it held the things it was meant to hold. “It ingests the scanned books,” she explained. “And then it remembers where they are.”

“It doesn’t remember,” Molly protested. “It doesn’t ingest. I mean, I wish!”

“Well, call it what you want,” Janet said, cheerfully. She didn’t care what anybody thought. She knew the robot worked the way memories worked. All the big things stored together: a father’s death, a first kiss, a penis on the subway. All of this in the same bin. Winning ten bucks at slots, an argument with a Target cashier, a broken basement window: all stored together in smaller bins, just as accessible, if that’s what you were looking for.

She tried not to let it bother her that there had been a petition, signed by more than fifty faculty members, protesting the cost of the robot—almost two million dollars—which could have been put, according to them, to better use. What about adjuncts’ salaries? What about the computers that could no longer compute? “They need to suck it up and get with the future,” Janet had said to Molly. “The future’s so bright, I gotta wear shades. Remember that song?”

Molly smiled miserably and said, “We should get your robot a Twitter account,” and Janet felt a swell of gratitude.

Ronnie Rogers was a fast walker, but he’d always been a fast walker. He had the orange cube case gripped in his left hand, because even back from the dead he was still left-handed. Or not from the dead: He’d faked his death, obviously. “Ha,” Janet said out loud, dodging a beeping cart bearing an elderly couple. He’d been big on practical jokes. He liked movies with twists at the end. Faking one’s death did seem like a strange thing to do, but—as Janet liked to say—it took a lot to surprise her these days. Nothing seemed entirely out of the realm of possibility. Last summer, they’d had a problem with students making a racket in the library as they tried to catch invisible monsters with their phones. And last spring, there had been an active-shooter alert, and Janet, Molly, and three students spent an hour crouched in the locked technology classroom waiting to die. The text messages brought news of carnage. One shooter, then two. Seven dead in the library; cafeteria workers shot in the dish room. So specific. Then it turned out there wasn’t a shooter at all; it was a false alarm. All clear. All fake. What could you make of a world where two things were true at the same time? For instance: Ronnie was dead. But also, Ronnie was alive, and striding very quickly through the Atlanta airport.

She joined the surge of people heading for the escalators that led down to the plane train, finding herself lodged behind a large family with a stroller. She could just make out the glow of Ronnie’s now-bald head far below. He looked as if he’d forgotten to apply sunscreen, like maybe he’d spent the summer—doing what? Boating? They’d gone boating once, in Annapolis. They’d eaten ham sandwiches and drunk lukewarm wine on a blanket on a hill, and had sex in the crabgrass.

That was a bin she wasn’t expecting to open, but voilà, there it was.

She pushed her way down the escalator, her rolling bag thwumping behind her. “The plane train is now approaching,” said a friendly automated female voice. She sounded like a gentle robot, like she might have a little face and hands. The plane train slid to a stop; the doors heaved open, the crowd surged, a teddy bear backpack struck her softly in the chin. Janet could see Ronnie up ahead; he boarded. She boarded, one car behind, moved to the front to stare at him through the glass. What if he looked up and saw her? She moved behind a tall woman with spiky red hair. But he wasn’t looking.

It occurred to her that even though she could remember the itch of crabgrass on her thighs, she couldn’t remember if his obituary had mentioned children. Wait: had she actually seen his obituary? And now that she was thinking about it, why was it that she’d thought he was dead? Yes: it was one Christmas when her mother said, while slicing carrots for a stew, “Too bad about Ronnie. Motorcycle accident.” But Janet had been involved with Evil Vernon, who was taking up all the space in her brain. She’d felt a small pang. But, really, a sense of relief, closure. So he was dead: You couldn’t get much more closed than that.

The train was stopping at Terminal C, “C for Charlie,” the female voice said helpfully. In the car up ahead, Ronnie was staring down at his phone. It was starting to seem as if perhaps he wasn’t just not-dead but had never been dead; had been, for the past twenty years, doing whatever it was he did, living where he lived.

Would he recognize her, with the same hair and body but a different, older face, the kind of face that would make more sense if she were more woman-sized, not wearing a training bra from Walmart? She’d more than once turned around and startled a teenage boy who’d been following her. Today, she was wearing her baggy sweater and leggings, which she would swap when she landed for the pantsuit folded neatly in her bag.

The train slid into B for Bravo. She watched him through the glass. He stayed where he was, so she stayed where she was.

There had been fights. He called the cops on her, then she called the cops on him. She threw his clothes out the window into the rain. Once, she sliced her wrist with a serrated kitchen knife and he found her crying and bleeding under the covers, carried her into the bathroom and ran the tub full of warm water. He gently removed her clothes, washed her, dried her, and bandaged her, and then tucked her, towel-swaddled, back into the bed. This was before the jasmine-smelling woman. This was just their life together.

File under Adultery. File under Divorce. File under Gave It a Good Try. After she’d been in Alabama for a couple of weeks, he showed up on her doorstep. It was almost midnight. “Just let me in,” he shouted through the door. And she shouted back: “No!”

When she’d heard he was dead (had her mother actually said “dead”?), she’d thought: There’s nothing to apologize for now.

The train hurtled into the station for A gates, “A for Alpha,” and as the train slid to a stop, she felt her phone buzzing deep in her purse: a text message from the librarian who was picking her up, saying he would meet her in baggage claim. Looks like your plane is taking off, finally!

It was?

The doors slid open. She stepped out of the train, around a wheelchair, a schnauzer, a troop of Girl Scouts in their green sashes. And watched Ronnie disappear into the crowd surging toward the escalators.

The grad student had managed to steal hundreds of books before Molly caught him. He would fill his backpack with them, cart them home, and sell them on eBay: medieval French literature, physics books from the 1950s, Russian textiles and Finnish fairy tales, a history of the Canadian education system, windmills, codfish, candle-making. Molly had sobbed when she saw his mugshot in the local paper, then said, “Well, that’s less to scan anyway,” and wiped her eyes. Some of the books had been rescued, but others were out there in the world, with their musty smells and their hard bindings and their pencil-marked notes from long-ago students. Gone forever, but yes—there was less to scan. Less to shelve, less to pile into bins according to size.

At the top of the escalator at the intersection of the A gate corridors, Janet paused in the crowd flowing around her. Ronnie could be in the CNBC News store, or the Boar’s Head, or P.F. Chang’s; he could have headed in the direction of A33 or toward A1. A group of backpacking teenagers strode past, laughing. Families with tiny children on leashes. A blind couple with canes stood side-by-side, the man with his hand on the woman’s shoulder, while a woman in a Delta uniform stood next to them, talking into a walkie-talkie.

It occurred to her that she could have Ronnie paged: You’ve left another personal item behind. And then she heard herself being summoned: “Janet Rogers. This is a courtesy warning. Please report to gate D13. Your plane is departing.” And she realized that she hoped Ronnie didn’t hear it; she hoped he was simply enjoying being not-dead, chatting on the phone with his wife, or browsing through a magazine, or doing anything but opening up that tiny drawer that held the contents of their life together. The blind couple headed off down the corridor, their arms linked; more backpackers streamed past. Her name came again, one last warning, one last courtesy, before the plane took off and left her behind.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.