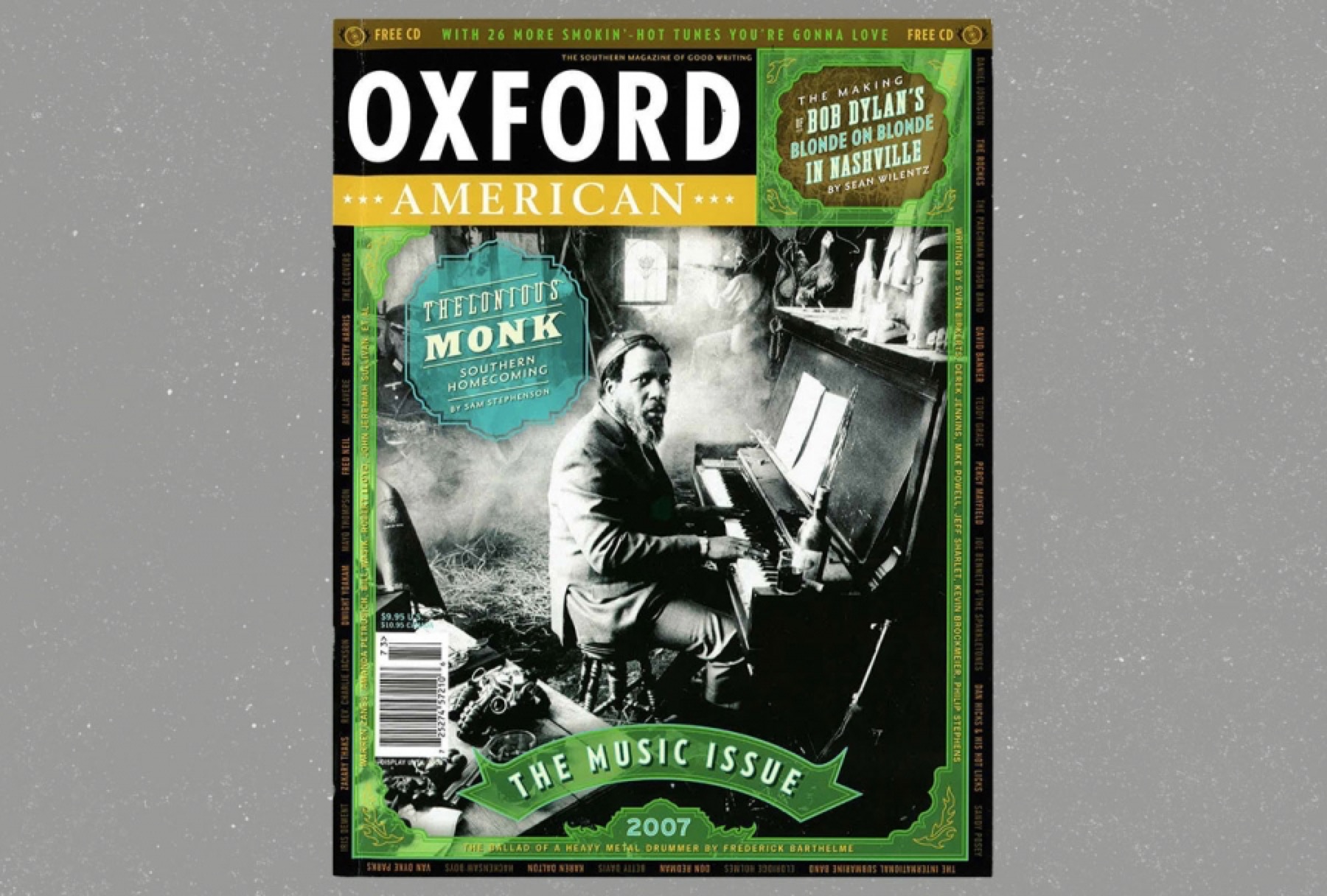

“SAINT MONK” (2018), by Andres Chaparro

Is This Home?

By Sam Stephenson

Silence is one of Monk’s languages, everything he says laced with it. Silence is a thick brogue anybody bears when Monk speaks the other tongues he’s mastered. It marks Monk as being from somewhere other than wherever he happens to be, his offbeat accent, the odd way he puts something different in what we expect him to say. An extra something not supposed to be there, or an empty space where something usually is.

—John Edgar Wideman, “The Silence of Thelonious Monk,” from God’s Gym.

On Friday May 15, 1970, fifty-two year-old Thelonious Monk and his wife of twenty-three years, Nellie Smith Monk, flew into Raleigh-Durham Airport and took a cab to a local hotel. In that day’s edition of The News and Observer a photo of Monk ran with a caption heralding “Star Returns” and text stating:

Pianist and Composer Thelonious Monk returns to his native North Carolina for a 10-day run at Raleigh’s Frog and Nightgown beginning Friday Night. The Rocky Mount native, long in the avant garde of jazz, has written several standards, including the well-known “’Round About Midnight [sic].”

The existence of a successful jazz club in Monk’s home state in May of 1970 was an anomaly. Woodstock (August 1969) marked the era and Led Zeppelin, the Beatles, Simon and Garfunkel, Stevie Wonder, and the Jackson 5 topped the charts. Jazz clubs were closing in bigger cities across the country while Raleigh, with a population of 120,000, wrestled with integration. But Peter Ingram—a scientist from England recruited to work in the newly formed Research Triangle Park—opened the Frog and Nightgown, a jazz club, in 1968 and his wife Robin managed it. Don Dixon, a house bassist at the club who later gained fame as the co-producer of REM’s first album, Murmur, says, “It took a naive Brit like Peter to not know that a jazz club wouldn’t work in 1968.”

The Frog, as it was known, thrived in a small, red-brick shopping center nestled in a residential neighborhood lined with nineteenth-century oak trees. Surrounded by a barber shop, a laundry mat, a convenience store, and a service station, the Frog often attracted large crowds; lines frequently wrapped around the corner. Patrons brownbagged their alcohol (the Frog sold food, ice, and mixers), bought cigarettes from machines, and some smoked joints in the parking lot. Ingram booked such jazz icons as Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry, Zoot Sims, Art Blakey, the Modem Jazz Quartet, and Stan Getz, as well as lesser-known but adventurous musicians like Booker Ervin and Woody Shaw. Due to its mixed clientele, the club came under threat of the Ku Klux Klan, but Ingram never blinked, and the Frog held on, exceeding all odds.

Six weeks earlier, Monk postponed his originally scheduled engagement at the Frog because of pneumonia, which hospitalized him from March 16 to March 31. He spent the month of April and the first half of May convalescing in his apartment in New York City. He probably had no business traveling anywhere for ten days, much less playing three sets a night, but the Frog offered his standard rate of $2,000 per week and Monk needed the money.

Despite two decades of recordings that made him a cornerstone of jazz, Monk’s life and career were spiraling downward in 1970. Columbia Records dropped him from the label and he was nearly evicted from his longtime New York apartment. Moreover, as he battled various illnesses and chronic exhaustion, his schedule became unpredictable, making it difficult to hire and keep musicians in his band.

On the morning of May 15, 1970, with the flight to Raleigh later that day, Monk still didn’t have a saxophonist for the trip. Monk’s old friend and bassist at the time, Wilbur Ware, first called alto saxophonist Clarence Sharpe but he couldn’t make it. He then called tenor saxophonist Paul Jeffrey, who jumped at the offer. Jeffrey tossed a portable Uher tape recorder and a new box of reels into his bags and met the band at LaGuardia Airport. “Part of the reason I got that job at that time,” says Jeffrey, a native New Yorker who had been considered for the Monk quartet before, “is because a lot of cats were afraid to go down South then. I’d toured the South in B. B. King’s band in 1959 so I knew the ropes. Plus, I wouldn’t turn down the opportunity to play with Monk if the gig had been on the moon.”

Over those ten days, Jeffrey recorded much of the music the quartet made at the Frog and Nightgown, and his tapes are remnants of Monk’s only major engagement in his home state. Jeffrey remembers the opening night:

I was nervous. I mean, this is Monk we’re talking about and his music isn’t easy. I remember the first night like it was yesterday. It is emotional for me to think about now. We played “Blue Monk,” “Hackensack,” “Bright Mississippi,” “Epistrophy,” “I Mean You,” “’Round Midnight,” and “Nutty” in that order.

Jeffrey’s recordings reveal a band in good form, driven by bassist Wilbur Ware’s familiarity with Monk’s shifting rhythms. Following a blistering, four-minute solo on “Nutty,” Jeffrey expresses a warm, deft sound on the ballad, “’Round Midnight,” bearing the influence of Dexter Gordon. Drummer Leroy Williams provides a rhythmic platform for the band. No matter his physical condition, Monk sounds remarkable.

Monk’s arrangements blended gospel, blues, country, and jazz influences with a profound, surprising sense of rhythm, often using spaces or pauses to build momentum. The idiosyncrasies of his music made it difficult for some fans and critics who considered his playing raw and error-prone. But those criticisms came from classic European perspectives in which piano players sat still and upright in “perfect” form. Monk played with flat fingers and his feet flopped around like fish on a pier while his entire body rolled and swayed. In the middle of performances, he stood up from the piano, danced, and walked around the stage, then rushed back to the piano to play, sticking a cigarette in his mouth as he sat down.

In a remarkable 1963 appearance with Juilliard professor and friend, Hall Overton, at the New School in New York, Monk demonstrated his technique of “bending” or “curving” notes on the piano, the most rigidly tempered of instruments. He drawled notes like a human voice and blended them (playing notes C and C-sharp at the same time, for example) to create his own dialect. Overton told the audience, “That can’t be done on piano, but you just heard it.” He then explained that Monk achieved it by adjusting his finger pressure on the keys, the way baseball pitchers do to make a ball’s path bend, curve, or dip in flight.

Influenced by his devoutly churchgoing mother, Monk’s music was born out of black gospel. When he was sixteen years old, he dropped out of New York’s prestigious Stuyvesant High School, where he had gained admission on merit, and soon embarked on a two-year tour playing piano for a female evangelist. This experience solidified his extraordinary musical architecture. The pianist Mary Lou Williams first met Monk in Kansas City while he was traveling with the evangelist and she reported that he was already playing the music he later brought to the jazz scene in New York.

The syncopated Harlem Stride style is said to be the foundation of Monk’s music and that’s not false. It’s just not the deepest root. Here is how the father of Harlem Stride, Willie “the Lion” Smith, described his own music:

All the different forms can be traced to Negro church music, and the Negroes have worshipped God for centuries, whether they lived in Africa, the Southern United Stares, or in the New York City area. You can still hear some of the older styles of jazz playing, the old rocks, stomps, and ring shouts in the churches of Harlem today.

Lou Donaldson, a member of Monk’s band that recorded “Carolina Moon” in 1953:

My father was an AME Zion minister in Badin, North Carolina, and the Albemarle area and one of the reasons I was so drawn to Monk’s music was because I recognized right away that all of his rhythms were church rhythms. It was very familiar to me. Monk’s brand of swing came straight out of the church. You didn’t just tap your foot, you moved your whole body. We recorded “Carolina Moon” [in 1952] as a tribute to our home state, with Max Roach on drums. Max was from Scotland Neck.

The seventy-nine-year-old saxophonist Johnny Griffin, who played with Monk often in the 1950s and ’60s, says today, “l never knew a musician whose music was more him—I mean him—than Monk. His music was like leaves on a tree. His music grew from nowhere else but inside him.”

The jazz books agree that Monk was born in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, in 1917, but beyond that his family background is mostly unknown. His Frog and Nightgown engagement is treated as merely another entry in scholarly chronologies of his career, no more significant than gigs in Michigan or California. From the research of Gaston Monk (a retired school principal and NAACP leader in Pin County, North Carolina, whose grandfather was the half-brother of Thelonious’s grandfather), Erich Jarvis (a neurobiologist at Duke whose mother, Valeria Monk, was a cousin), and Pam Monk Kelley (an educator in Connecticut, whose father Conley Monk was a first cousin), some of Thelonious Monk’s roots emerge.

The white patriarch James Monk came to North Carolina in a wave of migrants from Scotland around I770. In 1824, his son, Archibald, married another Scot, Harriett Hargrove in Newton Grove, North Carolina. In 1829, Harriett’s father gave his daughter and son-in-law a young female slave named Chaney, and six years later he gave them a male slave named John Jack. It is probable that Chaney and John Jack—or their parents—came from West Africa and were traded in the markets in Wilmington, North Carolina, before being brought up to Newton Grove.

By the 1860 census, with the Scotch accent fading into a Southern Anglo-Afro drawl, Archibald Monk, then in his sixties, listed nineteen slaves in his possession, ten males and nine females. Among them were John Jack’s young sons Isaac and Hinton. Isaac and Hinton would become the grandfathers of Gaston and Thelonious respectively.

After emancipation Archibald Monk’s son, Dr. John Carr Monk, founded a Catholic church in Newton Grove. Newly constituted Methodist proclamations disallowing freed blacks from attending Methodist services (after being allowed to attend as slaves) angered John Carr. The resulting biracial Catholic church, Our Lady of Guadalupe, was consecrated in 1874 by Bishop Gibbons and still stands, its walls decorated with turnof-the-century photographs of both black and white members of the church. (While conducting interviews with Monk elders in the 1990s, Erich Jarvis identified a number of Thelonious Monk’s relatives in these photos.)

In 1880, Hinton Monk and his wife Sarah Ann Williams named their first son after his father, John Jack, and in 1889 they named their seventh child Thelonious. Biographer Robin D.G. Kelley, whose book Thelonious: A Life is forthcoming from the Free Press, suggests the unusual name could have come from a Benedictine monk named St. Tillo, who was also called Theau and Hillonius. Another theory is that it derived from a renowned black minister in nearby Durham, North Carolina, Fredricum Hillonious Wilkins.

Thelonious Monk, Sr., moved with several relatives to the tobacco and railroad hub of Rocky Mount, in the 1910s, where he met his wife Barbara Batts Monk, who gave birth to one of the most original musicians in American history, Thelonious, Jr., on October 10, 1917. The family lived in a neighborhood called “Around the Y,” named for the Y-shape intersection of the Atlantic Coastline Railroad roughly a hundred yards from their home on Green Street (later renamed Red Row). Henry Ramsey, who grew up in “Around the Y” before becoming a judge in Oakland, California, is writing a memoir in which he describes black railroad workers lighting campfires outside boxcars, playing harmonicas and guitars, and singing blues tunes—all marks of a tradition carried on by such North Carolina country-blues musicians as Sonny Terry, Blind Boy Fuller, and the Reverend Gary Davis. Thelonious, Sr., played harmonica and piano in almost certainly this Piedmont rag style. Three and four decades later, Thelonious Monk would write compositions mimicking train sounds such as “Little Rootie Tootie” and “Locomotive.”

The Monk family struggled. Jim Crow was in full force and, by all accounts, Thelonious, Sr., and Barbara had problems with their marriage. Barbara moved to West 63rd Street in New York City in 1922 and took Thelonious, Jr., and his older sister Marion and younger brother Thomas with her. Thelonious, Sr., tried to join the family in New York later in the 1920s but returned to North Carolina for, to us, unknown reasons. After 1930 his direct family apparently lost contact with him. Rumors in the family indicate that he was beaten beyond recovery in a mugging or, having a wicked temper, participated in a violent beating himself, or both. In any case, according to various extended relatives Thelonious, Sr., spent the last two decades of his life in a mental hospital in North Carolina before dying in 1963. Many relatives visited him, but not his wife and kids.

Barbara Monk was an only child and both of her parents died before she moved away from Rocky Mount at age thirty. The pain of those losses is one explanation for her moving to New York—to get away. But Barbara was a North Carolinian through and through. Her accent, the food she cooked, and, most profoundly for young Thelonious, the churches she attended with the family in New York were steeped in Southern culture.

The Monks weren’t the only family in their neighborhood with ties to the South. The 1930 census shows that of the 2,083 people who lived in the immediate vicinity of the Monk’s apartment on West 63rd Street, 480 were born in North Carolina, South Carolina, or Virginia. Another 489 were born in other Southern states, the rest in the West Indies and New York. The census also shows that the Monks had a boarder named Claude Smith who was also born in North Carolina.

When Nellie joined the family in 1947, she moved into the three-room apartment with Monk, Marion, and Barbara. “He was lucky that he lived with [us],” Marion said once. “You’ve got to have somebody behind you when you are following one road, because otherwise you can’t make it. All artists have to suffer—unless they’re at home.”

Monk lived with his mother until she died in 1955, when he was thirty-eight years old.

Another pillar emerged for Monk in the 1950s in the form of the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, a descendant of the English branch of the Rothschild family, who was a patron of many jazz musicians. The Baroness’s role, like those of the other women in Monk’s life, paralleled the role Theo van Gogh played for Vincent.

Freed from commercial pressures, Monk was able to wait for the listening public to catch up to his unorthodox music.

Monk rarely emerged from his apartment in New York without wearing a suit and tie and an exotic hat. (And according to Time magazine, Monk often wore a “cabbage leaf” lapel pin. Though he would have called it a collard green.) “Even when Monk and Nellie were living like paupers,” says his longtime manager, Harry Colomby, “he always looked like a king. He was only about six-feet-tall but the way he dressed and carried himself made him look six-foot-nine.”

Monk’s royal-like aura made him an effective bandleader. Musicians weren’t sure how to act around him, so they followed him seemingly spellbound, often learning to play music they didn’t know they could play. But Monk’s demeanor sometimes worked against him in the conventional world. In 1951, police discovered heroin in a car occupied by Monk, his friend, Bud Powell, and two other passengers. Monk silently took the rap for the heroin, which by all accounts, except the cops’, wasn’t his. He spent sixty days in jail. “Every day I would plead with him,” said Nellie in an interview in 1963, “‘Thelonious, get yourself out of this trouble. You didn't do anything.’ But he’d just say, ‘Nellie, I have to walk the streets when I get out. I can’t talk.’” When Monk got out of jail, his all-important New York City cabaret license was revoked and he wasn’t allowed to play in clubs for six years—all during the 1950s jazz heyday. He recorded several masterpieces during this period, but, without the license to play in clubs, he had limited opportunities to promote them. Nobody ever heard him complain.

After the Baroness helped Monk regain his license to play in 1957, he held a legendary six-month engagement at the Five Spot Club with fellow North Carolinian John Coltrane. But in 1958, Monk lost his license again. He and the saxophonist Charlie Rouse were riding with the Baroness to a gig in Baltimore when they stopped at a hotel in Delaware to get a drink of water. The hotel staff didn’t like something about Monk (they probably didn’t like that two black men were traveling with a white woman in a Rolls Royce) and they called the authorities. When the police arrived, Monk sat stoically in the driver’s seat of the Rolls, refusing to take his hands off the steering wheel, muttering he’d done nothing wrong. The officers proceeded to beat him while the Baroness screamed at them to protect his hands. The Baroness rook the rap for the marijuana found in the trunk, but the scandal forced Monk to lose his license for another two years.

When judged by the workaday world—or even by the working jazz musicians of his day—Monk’s personality and social habits were eccentric. Some observers believe Monk suffered from manic depression, with tendencies for severe introversion, and perhaps some over-the-counter dependencies (alcohol, sleeping pills, amphetamines). One of Monk’s bassists, Al McKibbon, told a story about how Monk showed up at his house unannounced and sat down at his kitchen table and didn’t move or talk the whole day. He just sat and smoked cigarettes. That night McKibbon told him, “Monk, we’re going to bed now,” and he and his wife and daughter retired. The next morning when they awoke, Monk still sat at the kitchen table in the same position. He sat there for another day and night without moving or talking or seeming to care about eating, just smoking. “It was fine with me,” said McKibbon, “it was just Monk being Monk.”

On a national front, Monk’s return to North Carolina in May of 1970 coincided with a period of historic chaos during which American casualties in Vietnam officially totaled over 50,067 dead and 278,006 wounded, and college campuses, from Georgia to New Mexico, erupted in protest and violence.

On the local front, meanwhile, two white men shot and killed Henry Marrow, a twenty-three-year-old black Vietnam veteran, in broad daylight in Oxford, North Carolina, on May 11. On Saturday May 23, the last night of Monk’s engagement at the Frog and Nightgown, seventy African-Americans were marching forty-one miles from Oxford to the State Capitol in Raleigh to protest the passive judicial treatment of Marrow’s murderers. On May 24, the day Monk flew back to New York, the caravan of protesters, led by a mule-drawn wagon carrying a symbolic coffin, grew to four hundred people and passed two blocks from the Downtowner Motor Inn, a four-story hotel near the State Capitol in Raleigh where Peter Ingram put up the Frog’s visiting musicians.

Neither Leroy Williams nor Paul Jeffrey recall the political events of 1970 as being on their minds during their Frog engagement. The attendance in the 125-seat club was, by most accounts, solid but not overwhelming. Bruce Lightner, the son of a funeral home owner and Raleigh’s first black mayor, Clarence Lightner, came home from mortuary science school in New York that week and was stunned to find Monk playing in Raleigh. “The night I attended the band was on, really on. I took a date and we got to shake Monk’s hand and it was a thrill,” says Lightner. Paul Jervey, the son of the owner of the black newspaper in Raleigh, The Carolinian, remembers the audience as being mixed but predominantly white. Henry M. “Mickey” Michaux, a black state legislator from Durham, remembers Monk wearing a medieval robe and boots that had pointed toes that curled upward. He recalls the Frog being about half full for the set he attended.

Leroy Williams recounts the night the Frog’s staff presented Monk with a white homecoming cake ornamented with a fez in honor of Monk’s famous passion for odd hats. “It had icing that said ‘WELCOME HOME TO NORTH CAROLINA,’ and Monk was very enthusiastic about it,” Williams says. “He was smiling and he said, ‘Thank you. I’m from Rocky Mount. Thank you.’ Monk loved it.”

Monk’s trip to Raleigh seems to be the last visit he made to North Carolina and it was one of only a handful of times, at most, that he returned to his home state. That spring, just thirty-two miles from the Downtowner, Monk’s ninety-year-old uncle, John Jack Monk, was living near Newton Grove. Seventy miles away in Pitt County lived Monk’s cousin, Gaston. ln Raleigh, maybe seven miles from the Frog and Nightgown, were cousin Almena Monk Revis, her husband, and their seventeen-year-old son. These are just a few of the many relatives who lived near Raleigh at that time. When Gaston Monk inaugurated the annual Monk family reunions in 1979, four hundred people showed up. But there is little or no evidence that any of Monk’s relatives attended the Frog and Nightgown shows, or that Thelonious and Nellie sought out the family.

Monk’s North Carolina relatives apparently knew more about him than he knew about them. Reggie Revis, the son of Almetta Monk Revis, remembers being eleven years old and reading an issue of Time magazine in their family living room in Raleigh. The issue, published in February of 1964, featured a cover story on Monk, the first black jazz musician (and one of the first black people in general) to get that placement. “We subscribed to Time, Life, and Newsweek and I read all of them each week,” says Revis. “I was reading the article on Thelonious Monk and there was a big spread of pictures and my mother walked by and said, ‘You know he is our relative, don’t you?’ I was shocked. Nobody had ever mentioned his name to me before.”

Biographer Kelley says that at this point in Monk’s life he normally spent the entire day in bed resting for his gigs. But one wonders if it occurred to Monk or Nellie to try to track down family members in eastern North Carolina while in Raleigh. The relatives may have seen the STAR RETURNS write-up in The News and Observer or they may have seen Peter Ingram’s newspaper advertisements for the Thelonious Monk Quartet or his fifteensecond spots on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. On Sunday, May 17, Monk and Nellie may have had time to attend church and get back for that night’s gig at the Frog and Nightgown.

Monk died in 1982 after a long, infirm seclusion in the New Jersey home of the Baroness, where only a few people such as Nellie, Paul Jeffrey, and another close musician friend, Barry Harris, had any contact with him. He was sixty-four years old.

Soon after his death, Nellie and Monk’s sister Marion began attending Gaston Monk’s annual family reunions in Pitt County, North Carolina. Gaston’s son, William, picked them up at the train station in Rocky Mount, the same station where the five-year-old Thelonious had left for New York with his mother, sister, and brother in 1922.

During the mid-1980s, one of the Monk gatherings was dedicated to the late Thelonious Monk and his family. While working on his Monk genealogy, Erich Jarvis interviewed many Monk elders, including Nellie, in 1993, when she was seventy-two. (She died in 2002.) “Nellie started coming to the reunions,” says Jarvis, “in order to feel a closer connection to her dead husband. She also knew it was important to him or else she wouldn’t have done it. She was closing a circle for Thelonious.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.