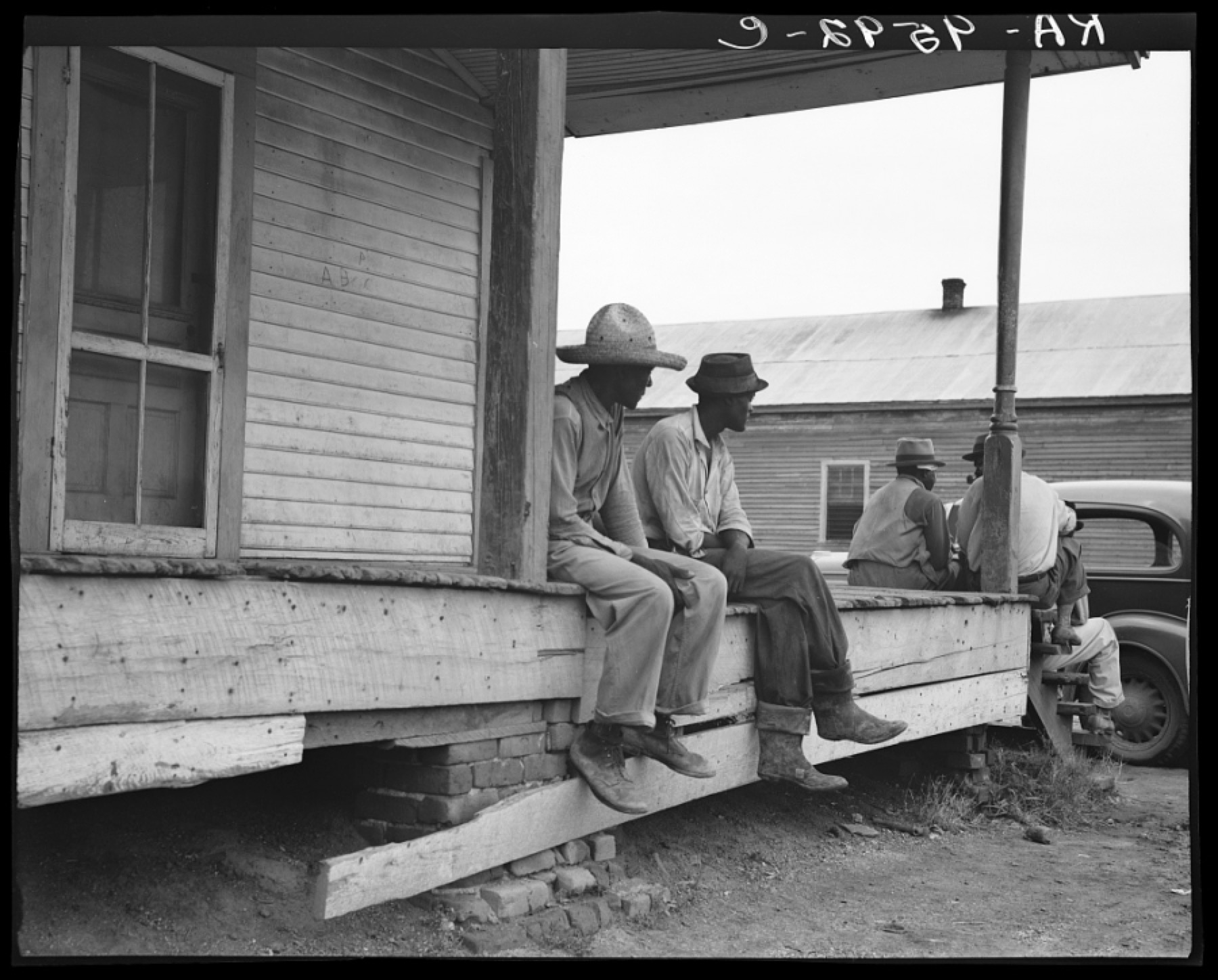

Storefront loafers. Mississippi Delta | Photo by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of Library of Congress

A Light Went on and He Sang

By Tom Piazza

It is always a shock to hear him again.

I first heard Charley Patton thirty years ago, on a two-LP compilation called The Story of the Blues, which I won in a contest. My adolescent ear was immediately sucked in by the mystery, the wit, the slyness, and the expressive variety of the performances of Blind Boy Fuller, Memphis Minnie, Texas Alexander, Leroy Carr, Barbecue Bob, Bessie Smith, Big Joe Turner, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Otis Spann, Blind Willie McTell, and the rest.

Nearly all the tracks, even one by a group of “Fra-Fra Tribesmen” from Ghana, felt somehow familiar to me. Each had a rhythmic or melodic handle to grab onto. But one track seemed nearly unlistenable: It was “Stone Pony Blues” by Charley Patton, recorded in 1934. Patton hollered and growled rather than sang; he sounded like a voice suddenly and belligerently addressing you from a nearby stool in a darkened bar. On top of that, his diction was nearly opaque. His vowels were stretched out, inflated from within; they expanded until they were all but unrecognizable. The words stone pony came out sounding like doughboanayyyy. What I eventually recognized as door sounded like duwowwwwahhhh. He added to the confusion by breaking words in half and by choosing odd syllables to accent. All of this was delivered by a voice from which any trace of varnish had apparently been stripped.

Patton was too much for me, like the first time you taste really strong black coffee as a kid. He left an aftertaste that burned. And yet, exactly because his sound felt so repellent, I wanted to come to terms with it. It seemed almost to be daring me to recognize it as a human sound.

To this day listening to him can be like having a caged tiger in the middle of your floor. Something is a little too close for comfort. On any given afternoon you might prefer to hear Tommy Johnson, or the Mississippi Sheiks, or Son House, or Willie Brown, or any number of others. But Patton ultimately exerts a greater claim on the imagination, for me at least. Underneath the surface, once you learn how to breathe in the atmosphere Patton generates, there is humor, subtlety, pathos, braggadocio, wit, and, the more you listen, an extraordinary musical sophistication. But that quality of being part of a time and a world that are lost to us adheres to Patton’s recordings in ways that remain palpable.

Charley Patton was probably born in 1891, of mixed black, white, and Native American ancestry, on a plantation near Edwards, Mississippi, midway between Vicksburg and Jackson. He was one of twelve children, only five of whom survived infancy. Before he was in his teens he had moved a hundred miles or so north with his family to the Mississippi Delta, to the now legendary Dockery plantation on Route 8, near Ruleville.

The Patton family was stable and even well-off by the standard of African-American Delta life of the early twentieth century. Patton’s father worked hard and eventually owned some land and a drugstore. His sister Viola married the man who ran the plantation grocery. Apparently Patton had some schooling: according to one of his nieces, Patton and Viola stayed in school through the ninth grade.

Beginning in the late 1910s and up to his death in 1934, Patton traveled all through the Delta, playing at house parties and in small makeshift barrelhouses for white and black audiences, and his songs are full of references to places and people and events of that world. The Mississippi Delta at that time was a backwater’s backwater. It was a very circumscribed area through which few outsiders made their way. Nobody thought much about documenting black life there. People didn’t have cameras; there are no snapshots of Patton hanging out on a porch with his friends or family, no pictures of dances where he played. By the time the WPA photographers and folklorists like the Lomaxes came through, Patton was dead. Except for a couple of trips north to make records, Patton almost never left the Delta.

There was no reason for anyone to think that the Delta’s people, landscape, and atmosphere would be immortalized. Other entertainers of the time—Bing Crosby, Maurice Chevalier, Fanny Brice, Rudy Vallee—came into homes by way of the Victrola or the gramophone. Jimmie Rodgers sang of the railroads and of traveling out West; Duke Ellington brought a new level of sophistication to African-American artistic expression. The medium of the phonograph was a road by which the Great Wide World was made available to the Local World. But it was also, as it turned out, a road by which news of the local, the idiosyncratic, and the personal made it out into the Great World. It was a two-way street, although people didn’t realize it yet.

When Patton made his first recordings in June 1929, he’d already been a well-known local musician for over a decade. Citified jazz- and vaudeville-influenced artists such as Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith had been making records with piano and jazz band accompaniment since the early 1920s. But in 1926 Blind Lemon Jefferson showed the companies that they could make money by recording solitary men with guitars singing the blues.

Patton’s first records were issued later in the summer of 1929, a few months before the stock market crash, and he had a couple of regional hits with “Pony Blues” and “Down the Dirt Road Blues.” Patton recorded much more than any of the other major first-generation Delta bluesmen—Son House, Tommy Johnson, Skip James, Ishmon Bracey, Willie Brown, and the others. But as the Great Depression deepened, the entire industry was hurt. Records were a luxury item, and those that were issued after the crash tended to sell less and less, until, at the bottom of the Depression—1931-33—very few records of any kind were selling anywhere, much less in the Mississippi Delta.

It is clear from the testimony of eyewitnesses that Patton was very much an entertainer. He would, apparently, do just about anything to get to an audience—play the guitar behind his back or around the back of his neck, stomp on the floor. He played blues, he played dance music, he played religious music, ragtime songs, sentimental ditties, and he recorded examples of all of it.

But it is, finally, his blues that occupy the center of his body of work. They burn with a fierce bravado and deep emotion. His titles themselves are a kind of poetry: “Heart Like Railroad Steel,” “Circle Around the Moon,” “Devil Sent the Rain,” “When Your Way Gets Dark,” “Moon Going Down,” “High Water Everywhere.” His lyrics are full of the names of towns and of the people who populated them: Natchez, Vicksburg, Clarksdale, Sunflower, and Belzoni; Sheriff Tom Rushing (spelled Rushen on the record label), Jim Lee, even Will Dockery, the owner of the plantation where he lived for most of his adult life.

If you figure in alternate takes and tracks on which he accompanied others, like the singer Bertha Lee and the fiddler Henry Sims, Patton made somewhere around sixty recordings. Certain lyrics and turns of phrase burn in the mind for keeps after you hear Patton sing them: “Oh, the smokestack is black, and the bell it shine like gold.” “My babe’s got a heart like a piece of railroad steel.” “Oh, well, where were you now, Baby, Clarksdale mill burned down?”

One reason why Patton’s recordings are so intense is that several different layers of what you may as well call discourse are going on at once. On most of his recordings, Patton hollers out his lyrics while using his guitar to both accompany and comment upon the main vocal line. In addition, Patton frequently adds another layer by making spoken asides, interjections, and questions in a slightly different voice. So he sings a line such as “When your way gets dark, Baby, turn your lights up high,” and immediately uses his “other” voice to say, “What’s the matter with him?”—as if he were standing there listening to himself along with you. Sometimes this other voice addresses the singing voice directly. All the time this is happening Patton is playing chords, bass lines, or little repeated riffs on the guitar. The result is a kind of three-dimensional listening experience. Patton summons up not just his own persona, but also an entire set of implicit dramatic relationships. A performance like “A Spoonful Blues” is practically an anthology of these devices, an amazing example of someone thinking and playing on several parallel lines simultaneously.

Some writers speak of Patton’s “imprecise” diction, but that word, with its implication of inadvertency, seems wrong. I would say that his diction often appears to be intentionally distorted. Words are broken in half for rhythmic effect; vowels, as mentioned, are stretched and pulled until they seem to be little more than sound for sound’s sake. But what a sound they make. Patton’s timing is staggeringly effective, his rhythm is elastic yet absolutely steady, and his intonation—for all the roughness in his voice—is perfect, and perfectly controlled.

His last records, made for Vocalion at the beginning of 1934 as the Depression was starting to be relieved by President Roosevelt’s efforts, came along too late to do him any good; he died in April, before they were issued. And anyway, by that time Patton was an anachronism. As the 1930s went on, the danceable, more urban sound of Peetie Wheatstraw, Sonny Boy Williamson, Tampa Red, and Big Maceo began to dominate the scene. There was scant appetite anymore for Patton’s kind of rough, uncut sound. Robert Johnson’s records of 1936-37 were a kind of throwback, the last big explosion in the munitions dump of the Delta blues. The slightly later recordings of Tommy McClennan and Robert Petway were little more than a footnote to the classic era of Patton and the others.

In the very late 1950s and early 1960s, it began to occur to a handful of young blues fans that some of the men and women who made the super-rare 78 records they treasured might still be alive and living in the Delta and environs. The guitarist John Fahey, collectors Dick Spottswood, Gayle Dean Wardlow, and a number of others looked in phone books, accosted people on the street, followed leads, and encountered the singers’ friends, cousins, nieces, sons, daughters, and, occasionally, the singers themselves. In this way Skip James was found, and Son House, Bukka White, Ishman Bracey, and Mississippi John Hurt, all of whom had recorded around the same time as Patton. But Charley Patton, of course, was long gone.

From interviews with these sources, a very sketchy life story for Patton began to be pieced together. In the late 1960s Samuel B. Charters included some of this material in a chapter on Patton in his book The Bluesmen. In 1970 Fahey published a groundbreaking study of Patton, including lyric transcriptions, musical analysis of the songs, descriptions of instrumental techniques Patton used, and what biographical material he had access to at the time. It was quite a while before anything like a full-scale biography could be attempted, and it appears that there never will be one. There just isn’t enough documentation—no diaries, no letters, no logs of engagements, calendars, pay records, accountants’ books. Researchers had to rely on the memories of a small handful of people who actually knew Patton and were articulate enough to convey some of what they remembered.

The closest thing we have to a biography is King of the Delta Blues: The Life and Music of Charlie Patton, by Stephen Calt and Gayle Wardlow (Rock Chapel Press, 1998). It is in some ways a valuable book and in other ways an unfortunate one. It gathers together a lot of information but in a disorganized and sometimes nearly unreadable fashion. Calt, who has also written books on Skip James and Robert Johnson and who seems to have done much of the actual writing here, has a style full of a puzzling mean-spiritedness and pomposity. For some reason the authors rely on Son House’s negative evaluations of Patton’s musical abilities, which were transparently motivated by professional jealousy. Calt’s own musical analyses verge on gibberish. For example, he calls “When Your Way Gets Dark” a “12 and 1/4 bar” song that “begins with an amputated six beat vocal phrase that is followed by an unexpected instrumental measure. . . . An unorthodox eleven beat bottleneck figure, capped with a conventionally fretted six beat bridge, follows a repeating of the tonic riff.” Huh? There is worthwhile material to be had in this book, just as there is nutriment to be had in a plate of fish that is filled with tiny bones. Eat carefully, and swallow nothing whole.

The good news is that the late John Fahey’s remarkable company, Revenant, which has put out landmark collections of Dock Boggs, Charlie Feathers, the Stanley Brothers, and others, will shortly be releasing a seven-CD set, Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton, which will include every note Patton played, as well as recordings by his closest associates, recordings of interviews with those who knew him, a full reprint of Fahey’s 1970 book, as well as essays, lyrics, reproductions of ads for Patton’s discs, and photos of every Patton record label. This set should go a long way toward being the definitive word on Charley Patton and his surroundings.

A final remark: when you acquire Patton’s music today on CD, you face an array of at least twenty tracks, back to back, ready to go. But putting the CD on and letting her rip may not be the best way of listening to these recordings.

The music of Patton’s that we now have comes down to us not from pristine masters that have been sitting in a record company’s vault; they have been transferred from extremely rare and worn shellac discs, each of which once belonged to someone for whom that disc was a very important possession. They meant so much to the original owners that they would often be played until the grooves disintegrated.

The performances were not assembled digitally in a modern studio, with overdubbing and multitracking. Patton walked into a room and sat in a chair; a light went on, and he sang. Then the light went off. Charley Patton opened a window in time for himself. And the real meaning behind that voice and that guitar reveals itself only over time. Be glad.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.