"Group Selfie," acrylic and rhinestones on canvas, by Juan Arango Palacios. Courtesy the artist.

When the Barrios Hear Her Song

By Verónica Dávila Ellis

"TUYA SOY"

It is an eventful summer in Chicago. June 2018 inaugurates the short but warm and active months that blossom with festivals, beach days, and block parties. June is also Pride month, and many of the historically gay and lesbian neighborhoods dress in their best to commemorate our queer ancestors’ fights to advance LGBTQ+ rights. The simultaneous month-long Puerto Rican Festival of Humboldt Park culminates in the Puerto Rican Day Parade. Across the city, people don the distinctive monoestrellada, the single-starred, baby blue-, white-, and red-striped Boricua ensign. The political and cultural term Boricua is used to honor the Indigenous Arawak/Taíno name for the island, Borikén. This year, Pride and the Puerto Rican Festival converge in Chicago on one blazing sunny Sunday.

I make my way toward Paseo Boricua, where the huge metal sculptures of the Puerto Rican flag distinguishing the Boricua section of Division Street can no longer contain the outpouring of music, car horns, and shouts. An ever-growing crowd journeys to the park to witness superstar Ivy Queen headline the fest’s final day. Already, a couple hundred people have gathered in front of the stage, and a dear friend and I inch closer to the excited audience. Neon and fluorescent lights emanate from the necklaces and light-up toys distributed earlier that day at the Northside Pride celebrations. Parts of that group made the sweaty and rowdy procession here to the West Side just to see La Diva—the moniker with which Puerto Rican queers have christened La Potra, La Caballota, our Mare, our Stallion, Ivy Queen.

Ivy Queen is a performer who never lets you down. She makes her way up to the stage singing “Tuya Soy” from her 2003 album, Diva, wearing a bright fuchsia tulle top with neon green bike shorts that match the hand fan she gracefully swings to cool herself. Although originally a song that confronts a partner’s infidelity, “Tuya Soy” transforms into a love letter for her queer and Boricua audience in the context of today’s festivities; indeed, she is all ours and she gives us her all. The crowd goes wild, and at the end of her first set, she pauses to speak to us. Ivy Queen’s shout-outs, very much in the traditional reggaetón concert mode, acknowledge how her performance coincides with Pride. She dedicates the concert to the Puerto Rican and Latinx queers of Chicago and brings to the stage one of the Boricua LGBTQ+ organizers in attendance. Ivy Queen steps aside as they champion their fight for affordable housing for queer youth on the city’s West Side, forging a moment of solidarity within the typically heteronormative space of Humboldt Park. The Pride flags propped up amongst the crowd are a monumental contrast to the towering flags of Division Street, replacing the red and white stripes of the Puerto Rican flag with rainbow colors. Here, Ivy Queen reminds us of the need to include the queer community, not just symbolically, but physically, in nationalist cultural celebrations and political organizing.

This paramount moment is incredibly moving for me. As a displaced queer Puerto Rican in the United States, I often straddle two political and cultural spaces that orbit each other but don’t always overlap: the radical queer and trans movements on one side, and the nationalist and cultural Puerto Rican, Caribbean, and Latinx spaces on the other. Ivy Queen’s performance and the work of the leaders of LGBTQ+ Boricua Chicago blur those artificial boundaries, showcasing the possibilities for inter-communal solidarity and shedding light on the liberatory goals of both struggles. As a pioneer of reggaetón and one of its earlier global stars, Ivy Queen represents the origins of a genre embedded within histories of migration, resistance, and mass consumption. Listening to her voice, we tune in to a sonic map that traces multiple gender, racial, historical, and cultural crossings.

"COMO MUJER"

A year after her Chicago concert, Ivy Queen arrives at the first Premios Tu Música Urbanos in San Juan, Puerto Rico, to receive a Premio de Trayectoria award honoring her career and influence. The awards show, a milestone for reggaetón as a musical and cultural phenomenon on the archipelago, is the perfect stage for Ivy Queen’s red-carpet promenade. Flanked by a group of drag queens dressed in the various iconic ensembles that have characterized her style across the years, Ivy Queen’s grand entrance represents her history within reggaetón and Puerto Rican music more broadly through the bodies of trans women drag performers, disrupting the genre’s oftentimes macho, artificial performances of gender. This choreographed entrance subverts mainstream media’s transphobic and misogynist valuations of Ivy Queen’s artistry during the height of her career, levied through homophobic epithets and viral memes that misgendered her after plastic surgeries.

These attacks against Ivy Queen point to a gendered process of racialization. Recognizing this, one of the drag queens at the Premios showcases Ivy Queen’s mid-1990s underground look; her box braids, wrapped in a high-top bun, fall over a baggy, shiny silver tracksuit, with its jacket open to reveal a solid black tube top. She looks playfully menacing under thin sunglasses, big hoop earrings framing her face. Representing the particularities of Black and hip-hop fashion trends, this drag queen embodies one of the most transgressive iterations of Ivy Queen’s aesthetic. The hairstyle not only racializes her as Black but also resists middle- and upper-class Puerto Rican feminine aesthetic trends. A tracksuit marks her as a “tomboy.”

An essential accessory all the drag queens share is Ivy’s famous long, acrylic nails, which, according to interdisciplinary Latinx scholar Petra Rivera-Rideau, represent the kind of excess that troubles discourses of gender and whiteness. While the acrylic nails symbolize manicured femininity, their bawdy designs and extensive length push the boundaries of respectability by highlighting their artificiality. Ivy’s aesthetic is not only part of a strategy to stand out from the masculinized reggaetón environment. Paired with her rejection of overtly sexualized vocality (namely her refusal to reprise the feminized “Dame duro papi,” which responds to the male singer’s call in reggaetón songs), her self-fashioning also reconfigures listeners’ assumptions about gendered performances. The landscape of pop reggaetón lacks positive and accurate representations, patronage, and inclusion of queer and trans people. Thus, Ivy Queen’s performance positions queer and femme subjects as creators and innovators within this milieu. These tangible connections with LGBTQ+ communities, as Rivera-Rideau argues, open up space for more inclusive understandings of Puerto Ricanness, ones that acknowledge and incorporate Black subjectivities as well.

“REGGAE RESPECT”

Reggaetón is a Black and Pan-Caribbean musical genre born from multiple Jamaican, Panamanian, Puerto Rican, and Dominican crossings throughout the region since the early twentieth century. It has been a rallying cry for the racialized working class in the face of displacement, racism, violence, economic stagnation, and negligence. Sonically, it is Jamaican dancehall’s grandchild, most famous for its characteristic syncopated beat described by musicologist Wayne Marshall as “boom-ch-boom-chik.” Rapped and sung lyrics, an array of looped synthesized melodies, and samples that range from late ’80s wave to electronic dance music are paired with key rhythmic effects taken from Puerto Rican bomba, Cuban son, and Dominican merengue and bachata. During the 1990s, Panamanian DJs and MCs began translating the dancehall songs that migrant Jamaicans brought to the country into Spanish. These covers became popular amongst Caribbean transmigrants who then traveled to New York City and back to the archipelago. In Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, these songs connected with home-brewed musical traditions and the nascent hip-hop en español developed by New York Puerto Ricans. Throughout the later part of the ’90s and the beginning of the new millennium, Puerto Rican and Dominican DJs and beatmakers polished the dembow beat that defines reggaetón by working with new digital software like Fruity Loops, incorporating merengue-infused double beats, a cencerro effect on the back beat, and balladic and r&b style crooning in the singing, which became the standard formula for the current iteration of the genre.

Today’s reggaetón foregoes bass-heavy beats, softening some of the more radical elements of the genre by pairing guitar-laced melodies with heightened romantic and thinly veiled sensual themes. Media and industry support for artists whose images easily conform to white Anglo norms and cater to audiences outside of the genre’s cradle has produced a bland, standardized version of reggaetón that is easily consumed by inexperienced non-Caribbean listeners. Ivy Queen’s performances on and off the stage are at once oppositional and at the core of a genre she helped cultivate. They represent another way of resisting both the internal pressures of this cultural milieu and the outside forces of a major music industry determined to cash in on a burgeoning global phenomenon.

Ivy Queen turns her face away from the DJ, her back to an imagined audience and the other hopefuls that await their turn to rap.

“MUCHOS QUIEREN TUMBARME”

“Muchos quieren tumbarme, les digo / mira no que no van a poder,” chants Ivy Queen while auditioning for the reggaetón pioneer DJ Negro in 1994. She is the first woman attempting to join the foundational collective of rappers known as The Noise, a group of avant-garde MC’s transforming Caribbean rap. Inside the club that gives the collective its name, Ivy Queen turns her face away from the DJ, her back to an imagined audience and the other hopefuls that await their turn to rap. Facing the wall, young Ivy’s strategy against treacherous stage fright, she orients listeners to the relevance of her voice and delivery as the primary forces behind her performance. It redirects their attention away from her body and toward her sound, subverting the visual regime of women as spectacle only, a presence to be probed, a body that labors. Ivy Queen’s rapping, crooning, growling voice has always been a central and complex presence in the sonic corpus of reggaetón and Puerto Rican popular music. Challenging assumptions about women’s roles in performance, playing with the viewer while adoring the listener, this song portends the Queen’s sonic pathways. She announces, “Si cuando canto la gente / sabe que llegó la Queen lanena del reggae,” placing her utterances before her arrival, drawing listeners in.

Before becoming Ivy Queen, Martha Ivelisse Pesante Rodríguez was born in rural Añasco, Puerto Rico, in 1972. It’s not coincidental that her first forays into music were singing trova alongside her father, a guitarist. Trova, a folk practice of sung poetry inherited from medieval Spanish culture, is viewed as one of the traditional forms of cultural expression cultivated in the mountains of Puerto Rico. It was a medium through which everyday happenings were wittily conveyed and preserved. Ivy’s connections to “el campo,” the countryside, or what Puerto Ricans from the metropolitan area call “la Isla,” connect her experience to that of Southerners’ disarticulation from a national, hegemonic American identity. In the case of Puerto Rico, the endurance of the rural peasant, the jibaro, as a national character that represents all Boricuas, parallels this distancing with the assumed backwardness of the region.

While becoming reggaetón royalty, Ivy Queen negotiated how the jibaro figure contours where she stands in a genre that celebrates the urban man. In her second album from 1998, she self-identities as “the original rude girl,” referencing the feminized moniker intrinsic to Jamaican dancehall of a fierce, determined, and brazen woman. In order to authentically be this original rude girl, Pesante Rodríguez expertly juggles the gendered values of both opposing images. For Ivy, moving into reggaetón means embracing the journalistic nature of folk music traditions to reconfigure the aural narratives of urban Caribbean realities specific to communities across San Juan, New York City, Miami, and Santo Domingo.

“SOMOS RAPEROS PERO NO DELINCUENTES”

Images of New York City and other urban locales have become the dominant visual representation for Puerto Rican rap and reggaetón. After she won a spot in the collective, Ivy Queen’s first recorded song appeared on DJ Negro’s mixtape The Noise 5. Ivy rapped accompanied by her then husband, el Gran Omar, and later filmed a video alongside Baby Rasta y Gringo for the foundational anthem “Reggae Respect/Somos Raperos Pero No Delincuentes.” With New York City as the backdrop, the video locates underground music, reggaetón’s precursor, as part of the ample hip-hop zone. Just as Caribbean bandleaders of the 1970s branded an amalgam of Afro-Caribbean rhythms, sounds, and dances under the broad category of salsa by slowly cooking together the soundscapes of migrants from the Caribbean with the brewed soul and funk of Southern Black migrants, underground and reggaetón artists identify the Big Apple as a flame under the multicultural cauldron that made possible their versions of “Latin” music practices.

The video for “Reggae Respect” thus integrates stigmatized underground music within established Puerto Rican sounds. In the song’s lyrics, Ivy Queen warns against the conflation of rap with delinquency. In 1993, then governor Pedro Roselló activated the National Guard in Puerto Rico as part of his anticrime initiative “Mano Dura Contra el Crimen,” known in English as the “Iron Fist against Crime.” This nefarious mobilization, which lasted until 1999, effected dozens of raids into public housing developments, where the police and military interrogated and arrested residents suspected of criminal activity. During these raids, underground records as well as recording equipment were confiscated and their owners charged. Roselló and his Mano Dura campaign succeeded in effectively linking rap and underground music with criminality and violence, cementing larger associations between immorality and rap, crime and the caseríos. By enacting violence against communities under precarious living conditions, Mano Dura not only further marginalized impoverished residents of public housing, but effectively worsened the realities of these and other working-class racialized Puerto Ricans across the island. As a response to this widespread campaign, The Noise rappers showcased how their music instead promoted fruitful possibilities for social and economic mobility for Puerto Rican youth living in barrios and caseríos. At the core of the song’s message lies a simple but potent critique of the government: Underground music does a better job of caring for its own than the state.

Caring for her own is emblematic of Ivy Queen’s ethic and ethos. Rapping “en defensa vengo yo del derecho del rapero” positions her as the authority of underground, reggae, and reggaetón. While she has yet to fall under the archetype of the caring mother, in “Reggae Respect,” Ivy Queen demonstrates her lyrical and performative prowess by becoming the rebellious defender of those neglected by the government and targeted by society. Here, she effectively embodies the tensions found in her jibaro/rude girl persona as the perfect positionality from which to guard her own.

Ivy Queen’s rude girl heroine is famously deployed in her feminist anthem, “Quiero Bailar,” from her album Diva. The expression resurfaces repeatedly as a statement of protection, defense, and refuge, this time by affirming women’s autonomy on the dance floor and in the genre at large. The sexual politics of reggaetón, following the tradition of Jamaican dancehall and incorporating the blossoming gangsta rap of the moment, represents another defiant stance against the state’s fundamentalist attitude toward sex, sexual education, and health. By rapping about sex in raw and explicit ways, and often including the sounds—material and human—that distinguish sexual acts in and out of the bedroom, reggaetón music confronts the hypocrisy of the Christian-based morality of its society. Ivy Queen’s song sheds light on women’s place in this landscape. It references how women lead in perreo—reggaetón’s doggy-style dance—and sustain their right to seduce, sweat, sway, and ultimately enjoy other dancers’ company without it automatically implying an admission to sex. Promoting consent-based practices in sensual, sexual, and intimate dances and spaces has distinguished Ivy Queen’s approach to her craft. A craft she manages with the ultimate care.

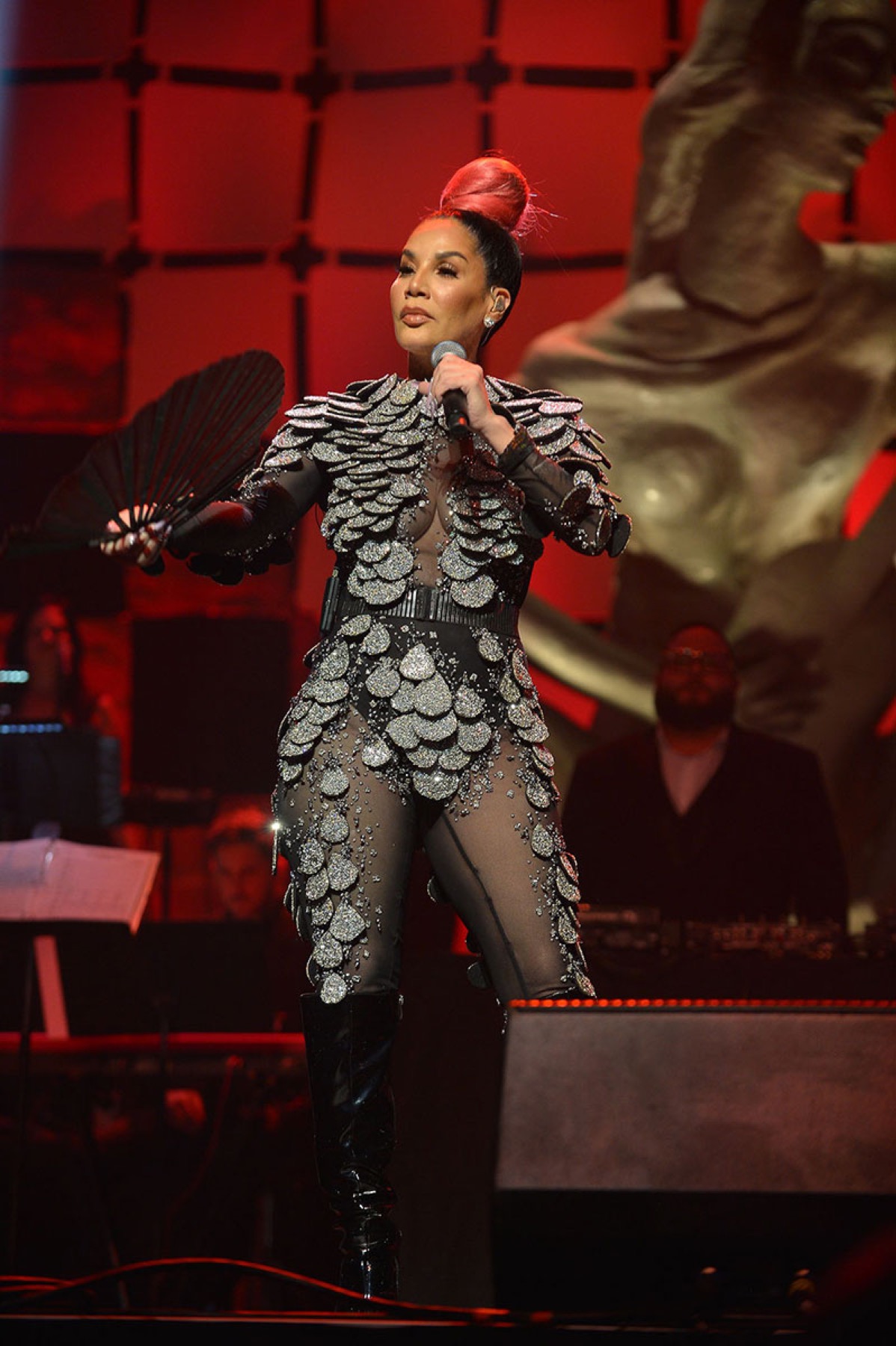

Photograph ©JLN Photography/Shutterstock

At the core of the song's message lies a simple but potent critique of the government: Underground music does a better job of caring for its own than the state.

“TE HE QUERIDO, TE HE LLORADO”

Care might be an ingenuous way of describing a voice that is otherwise full of strength and anger. To be sure, Ivy Queen’s ’90s rapping style carries the influence of coeval Jamaican dancehall singer Patra, combining ragamuffin sung bridges and rapped bars that sway and swerve, scratching at her throat, rolling through her tongue, blasting the speakers at the echoed bits of chorus as in “Reggae Respect.” She decisively does this “from el corazón,” from a heart ultimately set in reinscribing her community, women, and femmes as a generative force behind the growth of reggaetón as well as Black Caribbean music.

There is also much anger to be heard in Ivy Queen’s lyrics. Rivera-Rideau has analyzed how in Ivy Queen’s song “Te He Querido, Te He Llorado,” the murderous subtext of the chorus, “Lo que hiciste me las pagarás / si en mis manos tuviera un puñal lo usaría / y la vida yo te quitaría,” in which the singing voice threatens an adulterous lover with a dagger, repurposes the violence enacted against women in many misogynist songs. Killing, in this case, falls in line with the fantasy soundscapes of violence in the barrio and with reggaetón singers’ own embodiment of terror. Atmospheres of murder and menace were notorious in the work of Hector el Father and are most audible as the ubiquitous sound effects of guns unloaded and bullets being shot in popular songs like Daddy Yankee’s “La Gasolina” or Don Omar’s “Dale Don Dale.” There is also something fiercely ominous in Ivy Queen’s register that subverts the legible and auditory perceptions of masculinity espoused in reggaetón. Her incorporation of bachata in this song, a mashup practice celebrated as a unique reggaetón subgenre called bachatón, offsets Ivy Queen’s raging, enunciating voice with the romantic and sad atmosphere of ballads.

Bachata, often associated with blues music due to the emotional range of the working-class singer, is a Dominican musical tradition. It originally narrated the aftermath of heartbreak, the rejection of a loved one, and men’s anxieties over the rapidly changing domestic structures in rural towns, a consequence of the feminized migrations to Santo Domingo, Puerto Rico, and New York City in the late 1960s. In the song’s sonic arrangement, the arpeggiated loop distinctive of bachata ceases to give way to the murderous chorus, and Ivy, remaining in the sonic realm of the forsaken woman, asserts her desire to end the life of her former lover. Ivy Queen’s bold and amplified voice contrasts significantly with the characteristically emotive, high-pitched, and strident tone of traditional bachata singers and its modern expression by artists like Romeo Santos or Prince Royce. Santos, who rose to fame in the early 2000s as lead singer of the groundbreaking bachata group Aventura, is well known for his aching falsettos. Aventura and Santos expertly meshed r&b with traditional bachata, opening up the genre to new contemporary markets in the United States and beyond. Prince Royce, following the immense popularity of urban bachata, has crafted a more refined take on the sopranist bachata singer formula, continuing to play with feminized vocal affects.

“Te He Querido, Te He Llorado” is what Ivy herself describes as a “sentimiento.” That is, a song imbued with “feeling.” It’s this voice of sentimiento, one that seems to capture all feelings, holding them tight like a ball in her throat, that recalls the sometimes-obscured genealogy of Caribbean and Black women singers, whose voices have also had to contend with the histories of simultaneous embrace and erasure of their mastery. Scholar Licia Fiol-Matta has discussed how the Black Puerto Rican bolero singer Ruth Fernández’s vocal performance expresses an affect that reverberates in the chest, marking hers as a “masculine” voice. The dissonance perceived by audiences and bandleaders between Fernández’s voice and her body echoes the similar gendered mischaracterizations that emerge from Ivy Queen’s work. Fernández’s expert manipulation of vocal range and tonality, pacing, breathing, and vibrato is comparable to Nina Simone’s grip over her own vocal inflections. Both Simone and Fernández constitute essential foremothers for Ivy Queen’s expression of sentimiento.

Rivera-Rideau identifies “feeling” as the mode that conduces Ivy Queen’s inclusion of marginalized Black and LGBTQ+ voices into notions of Puerto Ricanness. Feeling, often spelled out as “filin,” is associated with mid-twentieth-century Latin American boleros in the same ways that soul references a deep emotive and experiential quality found in Black popular music traditions. The Queen of Latin Soul, otherwise known as La Lupe, surfaces here as Ivy’s immediate sonic precursor, an expert in the performative space of filin. Both women have been subjected to classist and racist valuations of their music, aesthetic, and gestures. More relevant though are the ways in which Ivy’s indexing of vocal sentimentality, her sung cadences and the texture of her vibrations, are a direct continuum of La Lupe’s famous shouted “yiyiyi’s,” the sonic expressions of her own trance-like performing state.

“LA VIDA ES ASÍ”

In “La Vida Es Así,” from her 2010 album Drama Queen, Ivy’s chanteo style of rap-singing surges from a new emotive dimension that unsettles the boundaries between soul, ballad, reggaetón, and electronic music. In contrast to “Te He Querido,” this song positions Ivy within the mainstream pop ballad music genre that has dominated Puerto Rican and Latin American markets since the last century. The chorus displays a remarkable sample of Ivy’s melodic depth, resounding in contrast to heavy synthesized loops. Here, Ivy’s balladic diatribes are echoed through carefully placed backup vocals, a chorus of crooning voices that enhance the raw chanteo. In a sense, “La Vida Es Así” cements Ivy’s versatility by referencing another major Puerto Rican woman singer, Ednita Nazario. Using gossip as a source, Ivy’s ascending pitch conveys emotional buildup, swelling from calmed hearsay to spiteful resignation, recalling Nazario’s own despondent but unyielding delivery. One of Nazario’s most iconic singles, “Lo Que Son Las Cosas,” displays a more desperate and pleading narrative, but showcases her signature fortitude within minor key harmonies, a style that Ivy Queen incorporates in her performance in “La Vida.” The genius in Ivy Queen’s reference to Nazario’s work lies in the sonic revamp of both pop ballads and reggaetón, as well as the renewed woman’s perspective in the face of rumors of betrayal, stolen lovers, and life’s inevitable misfortunes.

It’s telling that during Nazario’s highly anticipated 2006 concert tour for Apasionada, she sang a cover of “Te He Querido.” During this performance, recorded for the tour’s live DVD, Ivy Queen makes a surprise appearance. Both women’s distinct vocals complement each other beautifully. A Grammy-winning singer and composer, Nazario’s productions had nonstop radio play throughout the first decade of the 2000s thanks to her powerful voice and her feminized exploration of women’s liberation after heartbreak, asserting their independence and even their despondency as a source of empowerment. Nazario’s version of crude, mellifluous feminine rebukes is for pop ballads what Ivy Queen’s voice is for reggaetón and rap. This staging thus marks a milestone in Latin American popular music sung by women.

The album Drama Queen closes with a bachata version of “La Vida Es Así.” While not starkly distant from the melodic style of the original version, this track does away with the dembow beat distinctive of reggaetón and returns Ivy’s voice to a less produced vocality, welcoming the listener to a space of intimacy that broods with sorrow. Ivy expertly manipulates the emotionality felt in the variety of Caribbean music genres that speaks to the distinctive somatic effects of transient social, economic, and cultural contexts of the region. Her vocal movements are subtle, in that they require our carefully tuned ear to lean into the broad histories of sound living in the Caribbean and beyond.

There is no Puerto Rico without reggaetón, the song tells us, just like there is no reggaetón without Ivy Queen.

“787”

It doesn’t take much for the assiduous reggaetón listener to identify Ivy Queen’s instrumental place in the development of the genre. But for the casual listener, there exists “787,” a captivating homage to the songs and rappers that have built reggaetón. Following the popular hip-hop signifier for place, this 2019 single is titled after Puerto Rico’s area code. The song gifts us with an Ivy Queen that insists on her voice’s prominence in the history of the genre that housed her—by lauding Puerto Rico. The lyrics are a combination of various distinguishable reggaetón lines; fans can sing along to Tego Calderón’s joyous “esto es para ustedes pa’ que se lo gocen,” or Don Omar’s seductive “dile que bailando te conocí.” By framing the song as a travel itinerary through Puerto Rico, “787” defines Puerto Ricanness as reggaetón music itself and inserts Ivy’s voice at the center of this ever-evolving cultural phenomenon. There is no Puerto Rico without reggaetón, the song tells us, just like there is no reggaetón without Ivy Queen.

Ivy Queen’s voice resounds with this legacy during that memorable night in Chicago, and I find myself feeling a peculiar pride in being Puerto Rican. I’m not one prone to nationalist sentiments, but Ivy Queen’s presence sparks a collective euphoria that elicits a sense of belonging. During the concert, the audience and I put aside our Boricua woes: the ever-present aftermath of Hurricane María, the anguish over the decaying livelihoods of our people due to PROMESA, the neocolonial regime that put us here, the never-ending grieving. We hold those close by still, like Ivy’s rage when singing against a traitorous lover in “Te He Querido,” stabbing the air with her long, sharp nails and neon green hand fan. We stab the imperialist tyrant with our rainbow Boricua flags, with our hips pulsing against each other’s sweaty bodies. Dancing on our own or with one another, there is no other collective cry more powerful than the one we emit tonight. Ivy Queen knows the power of her voice. She wields it sharp as a dagger, glistening like the gems in her attire, and gifts us with its bliss and introspection. That voice stays with us. Háganle la reverencia. Let it reside close to you, within ear’s reach. Allow it to convey its mystery and excitement, to recall its riotousness and endearment, to resonate with the pulse and vitality of reggaetón.