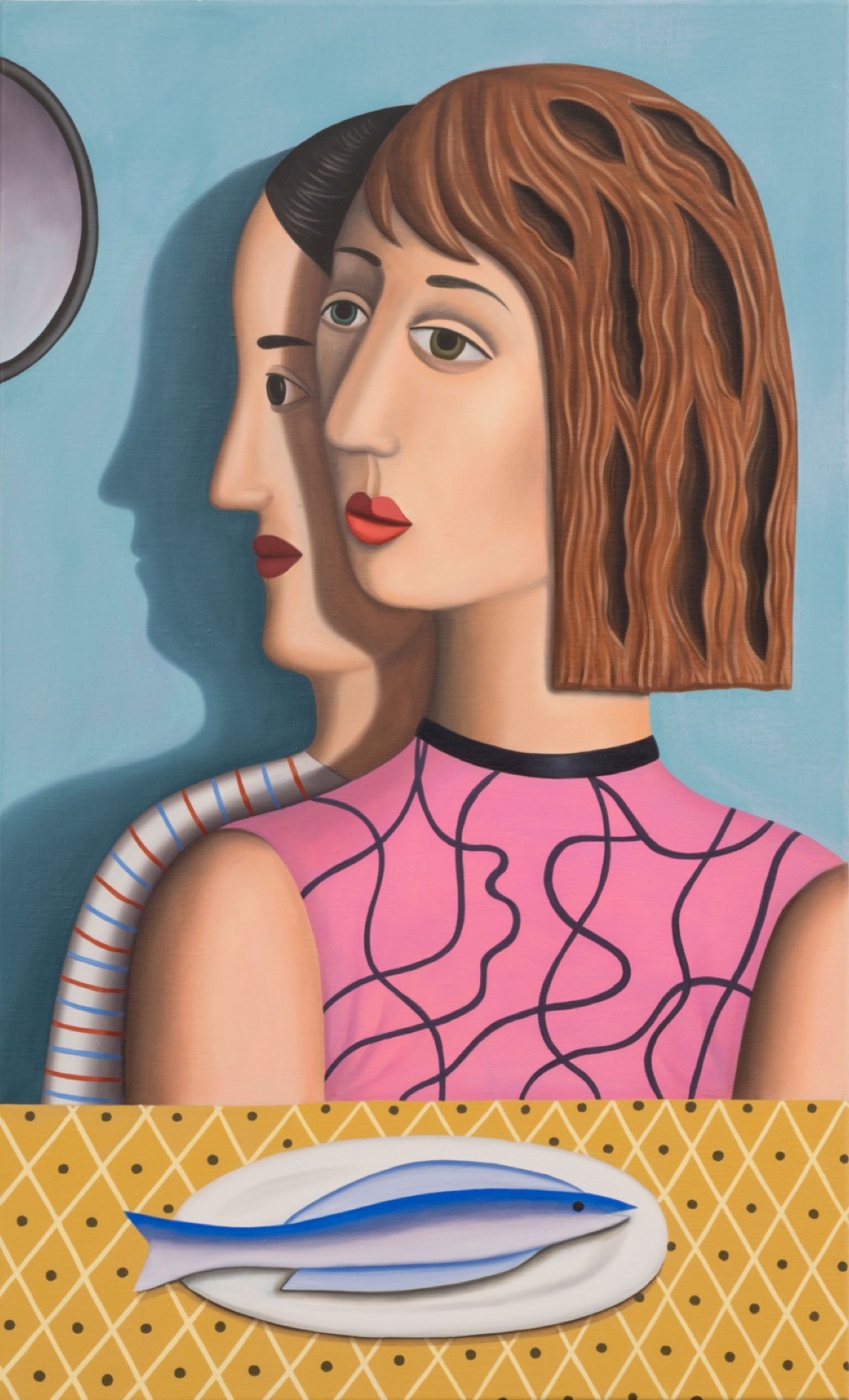

“The Shadow” (2015), oil on linen by Jonathan Gardner. Courtesy of the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York

The Stephanies

By Thomas Pierce

Oh Stephanie, this is not at all what you expected. You’re confused. All of us are, thoroughly. You’ve landed on a new planet and lo and behold it’s populated, incredibly, with other humans. What gives? What are the odds of traveling across the universe and finding people so eerily similar to yourself? Impossible, just about.

Welcome home, sister.

Welcome, willkommen, bonjour!

We’re here to guide you through this.

A home-cooked meal. A good laugh. You can rely on us.

A shoulder to—

Whatever you need, we’re here.

You still have a headache. It will go away in a few more days.

A week at most.

In your new kitchen is a bowl of small green leaves that resemble spearmint but—let this be a warning—do not taste at all like spearmint. Like, not even close.

These leaves, unfortunately, will remind you of tennis shoe deodorizers. Toilet bowl cleaners.

Awful, yes, but ball up a few leaves and stuff them between your bottom lip and your gums. A mild narcotic. The leaves are from a particular thorny shrub that grows in a forest a few miles away from here.

The drinking water here is rainbow-slicked, oily, and it tastes a little bit like almonds. Try not to think about almonds, generally, as we have none. No almonds, no peanuts, no pistachios, not even those big chalky ones that people always leave for last in the bowl.

Filberts, those are called. You’re a long way from the nearest bag of mixed nuts! There are a few nuts here, some of them edible, but none even half as good as the lowly filbert.

But the water is at least potable, so let us give thanks for that, shall we?

We try, always, to give thanks. Despite everything that has happened to us, we are still a spiritual people, mostly.

The sooner you accept this place as your home, the better. Happiness is not guaranteed. Not all Stephanies find it.

You have so many questions. You’re bursting with them. For starters, all these people and where the hell they came from, and so forth. How it is you came to be in a room with us. Boarding your ship, you weren’t sure you’d ever again see anyone other than your fellow passengers, yours being a one-way mission. Quite possibly you were going to die, tragically, en route.

And yet here you are in a settlement on a distant planet with running water and electricity—spotty as it is—and here you are surrounded by us.

Think of us like sisters, maybe.

You can trust us, certainly—but as for the rest, it’s just like it was back home. Good apples and bad. So stay wise like the serpent; cunning like the fox. Not that there are serpents here. Or foxes.

Here’s the deal, Stephanie; here’s what’s going on: Every year the exact same ship arrives carrying the exact same ten passengers. Nobody knows why. We’re caught in some sort of time loop.

Every landing is celebrated with a festival. It’s a real pageant, highly anticipated. We gather in the forest on the appointed day for games and food, and then we look to the sky to watch the ship descend, a ship identical to the one that landed the year before.

The ship’s flight path, since it is determined not by any pilot but by its programming, is more or less the same from year to year. Weather is the biggest variable and accounts for the largest discrepancies from its usual descent. With rare exceptions, the ship lands roughly two kilometers from our settlement in a large field of nearly translucent pinkish flowers.

Glass poppies, we call those flowers, and the heat coming off the ship melts them into a sweet and sticky black tar. The tar, collected into bowls, hardens quickly. We keep it in our kitchens, as it can be scraped into a crusty sugar.

It is for safety’s sake that we hold our festival in the forest and not in the field itself. We stay clear of the landing site until the ship has landed. For obvious reasons, we’re not allowed to build any permanent structures or plant gardens in this field. Generally, we regard this field as a holy site. It is a place to go and be quiet and ponder the universe’s great mysteries.

Chief of which, us.

At these festivals, you’ll find many craft booths. Homemade papers, fibrous and flecked with plant matter. Carved figurines. Braided belts. Shell purses, soaps, and painted eggshells.

We won’t even tell you what lays the eggs. Some things it’s better you find out for yourself.

You’ll hear lots of music at the festival, too. Mostly choral.

The ship lands at approximately the same time of day each year. The difference in arrival times is never more than twelve seconds or so. You’d think we’d cheer or holler or yell, but we don’t. We watch in silence as the ship touches down. Not an awed silence, really. More like: Ah, here we go again.

Once the ship is on the ground, once the metal has cooled, the so-called welcoming committee rushes onboard and removes the ten passengers before they have a chance to unthaw so that they will awaken just as you have, here in a cozy room with plenty of plush pillows and a nice view, surrounded by people who love you.

It is important, we think, that you know you have our love and support.

Are we overwhelming you, Stephanie?

Every year it is the same. Same festival, same ship, same passengers.

At any given moment, you see, there are about fifteen Stephanie Blocks on this planet. Fifteen Tripp Ashes. Fifteen Sam Motleys. Fifteen Prisha Patels. You get the idea.

We came here to this planet to start over again, to make a better, kinder, more spiritually attuned civilization, and in some ways we have, sort of.

A confusing fact that will require some time to really comprehend: Many of the people living on this planet right now—about ten thousand people at last count—are your descendants. Your progeny. Your children’s children’s children’s children’s, etc. It’s hard to know what to call them exactly. You are related to so many of them, genetically, to varying degrees.

In some of their faces you will see echoes of your own. A woman you pass on a walking path will have your out-turned big toes. A small freckled boy, your eyes.

Think of Adam, Eve, and their descendants, the beginning of humankind on Earth, the mystery of who was begetting who and with whom.

The locals, as we call them, are not truly local. As far as we can tell, this planet was not populated with humans until we arrived here for the first time. Whenever that was.

You’ll hear people refer to this as the year 1002, but the truth is that we’re not entirely sure how long we’ve been landing here. Yours is the 1002nd ship to land since we’ve been keeping a proper record. However, we have discovered the ruins of other, older settlements dispersed throughout the jungle, evidence of large-scale conflicts and collapsed civilizations, so there’s really no telling how many landings there have been throughout the ages.

Time will confuse you here, generally. This planet is farther from its sun, meaning it takes longer to complete its revolution. One year here is equivalent to three years, three months, and eleven days back on Earth. Maybe it’s best we not dwell on time too much, for now.

If you want to keep thinking in terms of Earth-time, that’s fine. If you do, that means the next ship will be here in a little more than three years.

But for most people you’ll meet, the year begins and ends with the arrival of our ship. It is the way in which the settlement marks and understands the passage of time.

The average life expectancy for Stephanies is about sixty Earth-years, so you’ve probably got about twenty-five years to look forward to here. The oldest Stephanie, to our knowledge, lived to be seventy-six years old, and she died from a fever. She was a lovely Stephanie, one of the kindest. For most Stephanies, it’s cancer, in the end. Our medicine is somewhat limited. The yearly arrival of antibiotics is crucial to our survival.

Try not to get any wounds.

Breathing is more difficult here, the oxygen thinner, so pace yourself. Don’t overdo it. You should explore and get to know your new home, but you can’t just go running barefoot down the beach tomorrow morning, first thing. Give your lungs a chance to adjust.

If you overdo it, if you don’t take the proper time with this transition, you will regret it. Quite possibly you’ll just keel over and choke to death. It’s happened to more than a few Stephanies.

You still don’t believe this is real. Understandable. You want some proof. Something no one else could possibly know. The special handshake you and Marnie used in elementary school, maybe. What Papa said the day he ran off for good: Don’t forget to feed the dog in the morning.

Or how about this? Four nights before leaving Earth, despite your vows to the church and to the mission, you nubbed Danny’s friend Alex. Because why not, right? Like anyone would ever find out and even if they did you’d be gone anyway.

He took you upstairs to his apartment and opened a bottle of red wine that he said he’d been saving for a special occasion.

The wine was good—but not that good. Not special occasion good.

He took your hand and pulled you out of the chair and danced you around the living room to Frank Sinatra—Fly Me to the Moon—while his little fluffy dog watched from the couch, his eyes going back and forth in his dog-head as he tracked you two dancing. Back and forth you swayed, Alex’s hand sliding gently down toward your butt.

But it was only later, when you said you should go, that he made his move and kissed you and told you that he’d always wanted to nub an astronaut. And then he did, in the bed, not with any real tenderness but who are we kidding you weren’t looking for tenderness anyway. Part of you even wished he’d been a little more aggressive with his nubbing. You wouldn’t have minded it a little rougher. What is it about you that men always want to be so soft and careful?

It might seem like you were in Alex’s bed only a week ago—but no. Many years have passed since then. Best to forget him and everyone else. To let them all go.

You might fall in love here, though. It happens. Some Stephanies fall head over heels in love. If you fall in love with one of your descendants—or even if you just take one as a lover—you’ll have to make peace with the fact that you’re probably, sort of, related to this person, at least a little bit.

Better to reckon with this possibility before nubbing rather than during. It can be a major distraction.

Because mid-nub you’ll suddenly find yourself picturing hideous reptoid babies with Habsburg jaws. You’ll be birthing a child that can only intone monosyllabically, that drools always, that requires constant care. What would you do with a child such as that? Would you drown it for its own good or would you try to raise it in this semi-civilized new world that lacks an advanced health care system?

All sorts of terrible questions will flitter through your head, mid-nub.

Such deformities are exceedingly rare, thankfully.

No birth control here. No IUDs. No condoms. No pills.

There’s pull-out. Masturbation. Bestiality. Celibacy.

Some Stephanies choose to remain alone forever. That’s an option available to you.

Do get to know us. There’s strength in numbers. We try to convene at least once a month. Potluck, that sort of thing. The conversation is easy.

Always we endeavor to be kind and supportive of one another.

A long hug from another Stephanie, at the right moment, can save you.

At some point in our history, a Stephanie designed the layout of our homes. The streets, the bridges, even the plumbing—all designed by Stephanies. These utilities and features, you’ll be pleased to learn, serve us very well. They function exactly as they were designed to.

So you should be proud. Proud because had you been the Stephanie charged with those tasks, way back when, you would have designed them in a similar fashion.

You might, however, be called upon to make a repair from time to time. To troubleshoot. To help install the new domiciles and equipment we take off the ships.

The streets are a series of concentric circles intersected by two long diagonals. Efficiency wasn’t the end-goal, of course, but mindfulness. Rarely is a street the shortest distance between two points. The streets, essentially, are there to slow you down.

The domiciles themselves are very simple constructions, very efficient, very spare, very Dwell-magazine, true to our spiritual principles of nonattachment and so forth. A Murphy bed in the living room/bedroom. The coffee table that doubles as storage container. The small closets that don’t call too much attention to the lack of fashion options.

The domiciles are all essentially the same, though small alterations are permitted. Some people prefer curtains, for instance. Some people paint the walls.

The two primary colors available in quantities large enough to paint an entire wall: blue and red. The red paint is made from the extract of a certain plant that is toxic if ingested. The blue is made from ground-up bugs, no joke.

Except they aren’t quite bugs, not truly. Believe it or not, put them under the microscope, and they’re more like hummingbirds. Very tiny and delicate hummingbirds. So delicate you could squash them between your fingers.

Be honest: Knowing that these creatures more closely resemble birds than insects, are you less inclined to use the blue paint? If you go and watch the paint-makers pulverizing these tiny hummingbirds into a blue paste, you may forever look differently at anyone with large blue walls in their domiciles.

Hummingbugs, we call them, and there is some solace to be found in the fact that they are so numerous. They repopulate quickly and are known to travel in giant cloud-like swarms. The swarms are very dangerous, actually. Avoid them, especially when sweaty, as the sweat attracts them.

The Garys have, over many generations, assembled a thorough taxonomy of this planet’s wildlife. It’s an ongoing project but a real accomplishment.

About the Garys we have much to say! Many Stephanies have married Garys, and while their love is not typically a passionate one, the Garys make steadfast and loyal partners.

But don’t expect major fireworks from a Gary Wizz in bed. You’d think a biologist would know a thing or two about the female body—but no. You will have to be very direct and clear about what it is you want from him when nubbing. He will need directions. Once directed he will do exactly as you say, which is good, for a while, but unfortunately, if you’re not careful, these instructions will become his go-to moves, his default mode, and his lack of spontaneity and creativity—his seeming inability to deviate from the instructions—will begin to irk you. Irk you to such a degree that you will have to give him further instructions, new ones which may or may not contradict the earlier ones.

Such contradictions will thoroughly confuse a Gary. “Do you even know what it is you want from me?” he’ll ask, and you will have to admit that you don’t, not entirely, because what you want is for him to anticipate and predict and surprise you. At this point in the conversation, he may become despondent and begin to doubt his abilities to please you sexually. A downward spiral. He will avoid you for a few days. He will sulk. And once he does return to you, he will, with some regularity, turn to you after sex with a look of hope and concern and dread and ask if you orgasmed and if you didn’t he will want to know why not and what he could have done better, and you will lie, probably, and say he was fine, it was you, you don’t every time and that’s fine, too.

You see where this is going.

But from a Gary you can expect this—you can expect a life of devotion and mutual respect. A true marriage of equals. Garys are dependable and patient fathers, though they have a hard time relating to smaller children. Kids younger than, say, four years old hardly register with Garys.

Getting a Gary to tell you how he’s feeling is no easy project. “I didn’t grow up talking like this,” he might say. Or, “Just tell me what it is exactly you want to hear and I’ll say it.”

Also, Garys tend to pack on the pounds as they age. Some become quite heavy. Even obese. They like to sport little chin-strap beards to mask the bulge of flesh that forms under their chins. But, after twenty years together, on some starry night, a Gary might turn to you and say, “I’d be nothing without you, I love you,” and you will feel a deep surge of pride and affection, but also, strangely, a twinge of regret—

Because all around you, these other Stephanies, with their various life paths, and all around you these other Garys, the ones who didn’t partner with a Stephanie, the Garys who chose somebody else or who stayed single and who seem quite happy in that decision, who contribute more to their research, who somehow avoid the weight gain as they age, who don’t seem to regret not having any children, who stride about the settlement with their butterfly nets, paying you no attention whatsoever. What of those Garys?

You will feel love for the children of all Stephanies. It can’t be helped. You’ll need a calendar, to keep up with all the birthdays.

There are ten days in our week, by the way. The days are referred to numerically, and we worship on the first and sixth days. You will be expected to attend worship on a regular basis. People look up to you here. They revere you, actually. So act accordingly.

Every so often a debate will erupt as to whether we should return to a seven-day calendar, but do the seven days of creation apply here as they do on Earth? A difficult question. God created this place, surely, but by which calendar? It’s a mathematical/biblical conundrum and probably not worth the time we give it.

There is much to say about the tiny elephant-mice which defecate nightly on our porches, but for now I will say only this: Sweep your porch every night before bed because even the smallest scraps of food will attract these creatures and once attracted they will never ever go away again.

You could take up gardening. Large farms ring the settlement, and food is plentiful, but starting your own garden is encouraged for mental health.

You can finally take up painting, by the way. You can be a painter, your mother be damned! Your skills as an engineer, though they qualified and recommended you for this mission, are no longer in much demand, those problems having largely been solved.

Your painting, it must be said, will require you to use the blue paint from time to time.

Every year the same ship arrives with the same people on board—but why? How? We have our theories.

Inadvertent passage through a wormhole or black hole or some other as yet undiscovered type of cosmic hole. A rip or ripple in the space-time continuum.

A planet with contra-temporal tendencies, like a clock running backward inside a larger one.

The various explanations are numerous and ultimately unhelpful because the fact is, year after year, the ship continues to arrive, and year after year, the same ten passengers continue to disembark. It is a fact of life for people here, not at all miraculous for its predictability.

Roughly fifteen Stephanie Blocks. Fifteen Tripp Ashes. Fifteen Gary Wizzes. Fifteen Sam Motleys. Fifteen Prisha Patels. Fifteen Kevin Hsus. Fifteen Amy Dalrymples. Fifteen Monica Dornes. Isn’t it incredible?

There are no Lucy Sizemores, however.

Lucy was admittedly a lovely woman back on Earth, a very capable and considerate doctor, the sort of doctor who warms her stethoscope with her breath before pressing it to your chest, but this planet changes her. Or rather, reveals her. Historically, Lucys always become a big problem. They connive. They dissemble. They are not team players. They can’t seem to help themselves. Even when informed of their own propensities and tendencies—toward violence, insurrection, and so forth—they are incapable of altering their personalities.

Lucy the Terrible, the most infamous Lucy of all, once led a great rebellion in which thousands of innocent people died. You can go and visit the site of the mass grave, if you’d like. There’s a plaque. Gives the entire history of that saga.

Lucy the Vicious is another one you’ll hear about.

Lucy the Strange.

Lucy the Demented.

Bottom line is, Lucys aren’t allowed anymore. It’s just safer that way.

Watching other Stephanies you will notice certain things. Things you don’t necessarily like. The gently sloped shoulders. The pear-bottomed ass, particularly in the heavier Stephanies. That dumb, vacant expression when you’re distracted.

You will notice certain unattractive behaviors, too. How pouty you can be, how moody. How much of a pushover.

But you are kind, Stephanie. Don’t forget that. You are beautiful, in your way. You have much to offer. You have a sharp mind. A big heart. You’re an artist!

Stephanies falling in love with each other is discouraged, for perhaps obvious reasons, but it happens. If you do take up with another Stephanie, be discreet about it. The sight of two Stephanies kissing in public would be sure to cause a stir.

Keeping an elephant-mouse as a pet can be a nice distraction.

You’re still thinking about Lucy, about what it means that she’s not allowed. No use in trying to sugarcoat it: Lucys are killed in their freeze-boxes as soon as the ship lands each year. We don’t even bother waking her up anymore. The way we do it, it’s painless. The idea isn’t to be cruel or vengeful for all the wrongs perpetrated by Lucys throughout history. It’s just better for everyone that no Lucys walk among us, that no Lucys be allowed to procreate.

But she does have her descendants among the locals. She lives on, genetically. That can’t be helped at this point.

Every so often you’ll hear it proposed that we should round up anyone with Lucy ancestry, just in case, and it’s important you stay on the right side of that issue.

About fifteen Stephanies at any given moment. Fifteen Prishas. Fifteen Sams. Fifteen Kevins.

Only one Michael Estes, however.

Now, Michaels are an interesting case. True alphas. There’s a reason Michael was selected as mission captain, after all. Individually they are natural and capable leaders—confident, self-assured, even-keeled—but put them in a room together and conflict is inevitable. They will squabble and fight. They will scream and yell.

At some point in our history, the settlement was governed by a Council of Michaels but eventually the Council became grid-locked with dysfunction, and so the Prishas seized control, temporarily, and instituted a new form of governance.

King Michael for a Year, the policy is called. Upon landing, each new Michael is given complete control of the settlement. He lives in opulence, exempt even from the rules of the church. Sort of like a dispensation.

He can nub whomever he pleases. He is waited upon by servants. A true life of luxury. The only catch is that when the next ship lands with a new Michael, the old one is chained and dropped into the sea.

How many governments there must have been, how many settlements, how many restarts.

You can go visit the Michael graveyard. In fact, such visits are encouraged. We have no moons, and, without waves or tides, the sea here is very clear, and when the weather’s good you can see all the way to the bottom where we drop the Michaels.

All those corpses. All those bones.

The dedication of a Michael to the sea is a very solemn event.

There’s a beautiful and provocative mural depicting this ceremony in the museum at the center of the settlement. It was painted by a famous Stephanie, in fact. Stephanie the Arch-Eyed. Most of the murals you’ll see were painted by Stephanies.

“Remembrances of Earth” is a famous Stephanie mural you might appreciate. For you it will conjure up memories of your old life—the coffee shop where you used to sit with your laptop, 3D-designing retaining walls for office parks; Papa’s convertible with the busted hood; the Washington Monument; interstate smog; snake-eyed dice; Grammy and Grampa Jake in their porch swing. For the locals, our descendants, the ones who were born here and who have never known anything else, the painting is a panoply of dreams, surreal and strange.

Something to remember: The locals have never heard of Rembrandt or Picasso or Matisse or Bosch. They’ve never seen a Frida Kahlo painting! Paint your feet in a bathtub with little scenes of Earth floating in the bathwater, and no one will ever know you’ve ripped off Frida. Paint ten thousand Stephanies posed in chairs, their exposed hearts connected by thin red vessels—small interconnecting threads, highways of blood.

Paint whatever you want!

For the people born here, there is no such thing as art history. Or rather you, being the first artist on the planet, are its history.

Your paintings can reference nothing but themselves. Your artworks, therefore, cannot be derivative.

There are other artists, of course, but more often than not the locals who paint are in helpless dialogue with your work. Your work is the standard against which all new art will forever be judged. You can never be avant-garde, it probably goes without saying. No matter how wild, how unusual, how unlike you, each new painting will be standardized and subsumed.

You can never be counterculture. Because you are the culture.

Not that there aren’t critics. The locals, though they revere us, are not afraid to write long, mostly well-reasoned essays about why a particular artwork of yours has failed to be beautiful or to inspire or to illuminate what it means to be human. You may act like these essays don’t bother you. You may even pretend that you haven’t read them. “I don’t have the time,” you’ll say. Or, “As a rule, I try to avoid all that.” But believe it: You will read those essays, and they will bother you.

Sometimes you’ll wonder why it is you paint at all. What, after all, do you have to offer that can’t be offered up by another Stephanie?

There is a range of behavior—a range of thought, even—of which a Stephanie is capable. To try and deviate from this range—to consciously engage in some very un-Stephanie-like behavior—only widens the range.

You can make a point off the curve, in other words, but you’re never off the graph itself. The graph of Stephanie.

Kevins’ books can be provided upon request, though we don’t recommend them. His murder-mysteries all follow the same basic pattern. Read just one and you’ve read them all. As for his attempts at recreating popular novels from Earth, you have to give him credit for trying but most of these efforts fall short. Don’t let him catch you laughing at them. Kevins are very self-serious and narrow-minded. They mostly keep to themselves.

You will wonder what it means that certain Stephanies manage to lead such remarkable lives, while others . . .

Stephanie the Blind is an important figure in the church. If we had saints, she’d be one. When Lucy the Terrible led her great rebellion, it was Stephanie the Blind who put a stop to the killing when she called a meeting between the factions and stubbed out both her eyes with hot coals. She quoted scripture. “If the eye causes you to sin,” she said, famously, “what use are they?” So impressed by this display were the leaders of the two factions that they agreed to cease the violence.

You wouldn’t call it Christianity, what the locals practice. Not exactly, not strictly speaking. Jesus figures into it, but so do we, the ten passengers who arrive each year without fail. You will understand this calibration, of course. We are a mystery, are we not? And what we do not understand, what cannot be understood, we must ascribe to God or else. Or else fall into a state of confounded hopelessness and despair.

Besides, maybe God really is responsible for what’s happening here, over and over again.

Or maybe God has nothing to do with it at all.

Stephanie the Stephanie is someone else you might hear about, as she was somewhat controversial for going about the land and preaching a doctrine of reincarnation. She claimed to have memories of a past life as Stephanie the Meek, who’s mostly remembered for her healing work with the victims of the Great Rebellion.

You can imagine the can of worms this opened, the idea of reincarnation, the idea that one Stephanie could return as another.

You’ll hear it said, by some, that we—all we Stephanies—are emanations of a single soul. That is to say, we are aspects of the same ur-Stephanie. An ultimate and underlying Stephanie which abides in each of us. When we gather together, you will wonder if this might be true, such is the bond we share, such is the understanding that exists among us.

Not that Stephanies don’t have their arguments. Because they do.

You will miss Earth, obviously. You will miss menthol cigarettes. You will miss lavender-scented detergents.

You’ll find that most of the locals are not much interested in what life was like on Earth. Try to describe fast food to them. Or traffic lights.

Or voicemails. The stock market. Wi-Fi. Action items. The light in their eyes will go dim. They’ll look down at their feet. They will change the subject.

Probably best to give up on the idea of originality. Of leading an unusual life. Of taking the path never taken. Nothing new under the sun and so forth.

No wrong decision, no bad choice.

Except, maybe try not to fall for a Sam. His dark curls, his brawniness, his sleepy-surfer’s eyes. You have chemistry, to be sure, but not once have things ever worked out well for a Stephanie and a Sam. Once a cheater, always a cheater, as they say.

“You should see this spot I found, way back in the forest, it’s so beautiful,” a Sam might say one day, brushing back his dark curls.

Or, with a certain lonely/giddy look in his eye: “Nothing ever gets past you, does it, Stephanie?”

In bed, Sams are a wonder though. Why deny it?

You are, for now, the youngest Stephanie. Only thirty-two Earth-years. That may not seem young to you now, but it is. Take advantage!

As you age you may begin to resent the younger Stephanies. Their bodies, their youth, the time they have left. You may be tempted to live vicariously through them. You will want them to succeed.

Or fail.

You won’t know what you’ll want for them, exactly.

The ship will land, as it does, and seeing this new inductee, you may roll your eyes and think, Here we go again.

Say you’re walking through the forest one afternoon and you happen upon a Sam, naked from the waist down, nubbing a much younger Stephanie against a low limb in a smooth-barked tree. Will you move on quickly or will you linger to watch? Will you feel jealousy or shame or lust or what? Will you, quite suddenly, feel your age?

If you’re walking through the forest one afternoon and you happen upon this scene, and if Sam, sensing an intruder, spies you, and if in his eyes you detect something—a mournful glimmer let’s say—a sudden and sad recognition that the beautiful young woman he is currently nubbing will one day resemble you (so wrinkled, so flabby, so worn-out), will you scuttle away quickly so as to not ruin their moment or will you stand your ground and remain unto them as a testament to the cruelties of time?

Don’t answer that.

About STDs, you need not worry too much. All passengers were tested, as you know, prior to departure, which rules out a lot.

Without any moons around this planet, you’ll only see stars up there. You could learn the new constellations—or not. Up to you.

It’s possible that one day, while standing in line at the cafeteria or while working in one of the gardens, you will see a man. This man will slump about with his hands in his pockets. He’ll have a long, bulbous nose and dark eyes. He will shrug a lot and have a shrill though endearing laugh. Seeing him, you’ll shudder. You’ll think, How? How is this possible?

But remember, this man, he’s not your Papa.

The more you study him, the more subtle differences you’ll notice. The mouth won’t be quite right. Or the hairline. The ears will be a little bigger or farther back on the head.

Still—and this will be difficult for you to process—some part of your Papa, through you, has survived. A stowaway in your DNA. You have brought him here, all the way across the galaxy. You have delivered him to this new world. Set him loose upon it.

You will consider, briefly, telling this man off. Giving him a shove in the chest. But that, you’ll decide, would be silly and unrewarding, he not being him, he not having his memories.

You may very well wind up following this lookalike around the settlement for a couple of days. You may watch him from a safe distance as he lives his life. If he has a wife and children, you’ll be especially keen to observe how he interacts with them, if he is doting or not, distant or not, brooding or dark-minded. If the children are nearly grown and he has not abandoned them, you will wonder what that means, but probably that will be the end of it and you will leave him be. You’ll keep your distance.

However, if he spends his nights out of the house, drinking with his friends, if he comes home and pisses against the living room wall and passes out on the sofa, you might be tempted to involve yourself. While he is away one afternoon, you might stop by for a little chat with the wife. You will have the urge to protect the children, at all costs. You might even become a kind of surrogate aunt to these children. A godmother, maybe. “If he ever. . .” you’ll say to them, not wanting to finish the sentence, not wanting to put any ideas in their heads that aren’t already there. “I’ll always be here for you,” you’ll say to these children, and you will be, because that is who you are.

And if this man, this lookalike, if he goes missing? If he falls down a hole one night on his way home?

Here’s something useful: The hairy-looking mushroom thingies you’ll see growing all over are edible. And delicious, too. You have to shuck off all the hair, but the meat is very succulent.

A Gary will tell you that mushroom thingies are actually part of one great big thingy, a super-organism, connected by underground microscopic tendrils. According to Gary, we should not be eating these thingies, since they may be sentient, but they really are so delicious.

As you might expect, on this issue, the question of whether we should eat the mushroom thingies, there are three camps: 1) Those who do not believe in the mushrooms’ awareness and who think we should eat them, 2) Those who believe in their awareness and who think we should leave them be, and 3) Those who believe in it but think we should eat them anyway.

You’ll have to decide for yourself what’s right as it pertains to the mushrooms.

Oh, Stephanie! Year after year the ships arrive!

Are they all out there—a long line of ships, one after the next, into eternity—or do they materialize in the universe only moments before entering the planet’s atmosphere?

A secret hope: That one year a ship will, for whatever reason, fail to appear. That on that sacred day, the day of its annual arrival, the sky will stay empty, the ship will not break through the clouds and whoosh down, blasting up those thick clouds of brown dust, whipping the trees violently, gushing exhaust and heat. You can imagine the confusion this would create, its sudden absence, that pleasing breakdown in the natural order.

A pointless dream, of course, because so long as there is a planet upon which to land, the ship will do so, plopping down indelicately, with a heaving crunch, its mouth sliding open dryly.

The people with their streamers, their barbecues, their music.

Always the ship returns. Always you return.

We won’t lie: Some days you’ll wake up and feel trapped. This will all feel like an elaborate punishment.

Nasty thoughts will fill your head sometimes. Watching them unplug Lucy’s box, watching them murder her in her sleep—let’s call a spade a spade shall we?—an idea might occur to you. Standing before your own box, looking down through the frosted glass at that familiar, pale face, briefly you will consider it, kicking loose the plug and putting a stop to all this.

But your nastiest thoughts do not define you. Stephanies are, on the whole, good.

Stephanie the Severe being an exception.

But still, on the whole, good.

Eventually, you might nurse a dying Stephanie. You will wash her soiled sheets. Hold her hand. Comfort her as best you can.

You will get her out of the house for a little fresh air. You will take her to the sea one last time. You will massage her calves, her back. You will wash her body, head to foot, imagining that with each pinch, knead, and caress, you are working her free from herself. You are ushering her outward—into the universe.

Because it can take a very long time, this process, you will tell her stories from the Earth days, the days you have in common. You will talk about Mama, her neediness, her frustrating passiveness, but also her laughter and the loose skin flaps between her fingers you loved to squeeze and smell. And you will talk about Papa, too. The time he took you to the fairgrounds but on the wrong weekend. The time he plopped a bag of frozen peas on your head after you tried to ride the neighbor’s Great Dane like a horse and got thrown down the concrete steps behind Johnny-Bird’s house.

You will be there with her at the very end. You will sing to her. You will ask her what she sees. You will be very quiet and listen. You will think about leaving the room—for a glass of water, for the toilet—but, sensing you shouldn’t, you will stay. And then, just like that, she will be gone.

The Prishas float their bodies down the river. The Garys are compost for the hairy mushrooms. The Sams prefer cremation. For Stephanies, it’s the cave.

We wrap our bodies tightly in sheets and carry them up the far side of the mountain together.

It appeals to you, doesn’t it, the idea of this cave?

One day your fellow Stephanies will wrap you in the sheet, of course, and we will take you up the mountain. We will deliver you into the darkness of the cave and pile the stones atop your body.

So many piles of stones. Stone piles on top of stone piles. In every crevice. Every nook. Every cranny. One day, surely, the cave will be plugged shut with us, and we’ll have to find another.

We will remember you on that day. We will join hands, just outside the entrance, and tell stories about you and laugh and cry. We will pray for you, Stephanie!

All this is too much, too fast.

We remember what it was like, being where you are now, at the beginning. You aren’t sure what to say or how to react. You feel crowded and closed in, exhausted and overwhelmed. We understand. It’s to be expected. Coming to terms with all this will take some time. Days, weeks, months.

Some of us don’t adjust for years.

Or ever, really.

But if you need to talk—

We’re here for you.

No wrong questions. No concern too small. Or too big.

For now, just get some rest.

And when you wake up, we’ll still be here.

None of us are going anywhere.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.