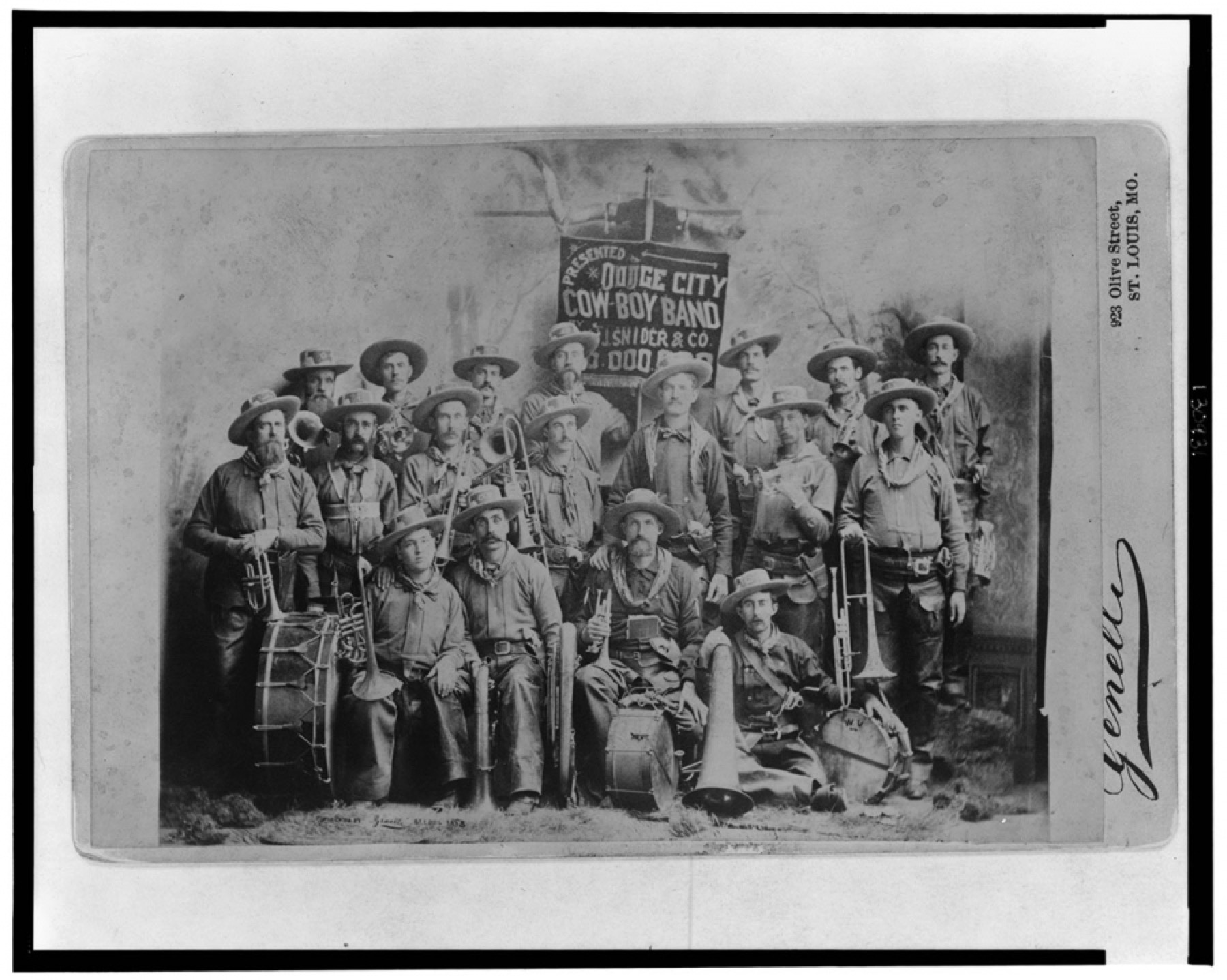

The Dodge City Cow-Boy Band of Dodge City, Kansas, ca. 1885; Library of Congress

SONG OF THE PIONEERS

By Joshua Brumett

I was present at the scene of a minor moment in the history of Texas music, although I remember very little of it. In the winter of 1994, I was four years old, sitting in the fellowship hall of the Methodist church in Henrietta, Texas, dressed as a small green dinosaur. I had just performed in the “Lasagna and Laughs” talent show and fundraiser, singing a selection from “Wee Sing Dinosaurs.” It was well-received, I think, but that’s not what this story is about. A band performed that night, for the first time in public—a band whose mercurial rise and untimely fall was to become the talk of Clay County for years to come, and who, in their own way, possessed the rare and true spirit of the Texas musical tradition. They were called the Sons of the Sons of the Sons of the Pioneers.

When Henrietta was founded in the 1850s, it was a real frontier town. White Texans were creeping west into the high prairie, and for a few decades Henrietta sat on the bleeding edge of that invasion. It was Comanche country and Kiowa country, and both of those nations were unhappy about the new settlement. Indians took the town in 1862, burned it down, and held the contested ground for almost a decade. In the 1870s, the settlers took it back and started ranching on the surrounding grasslands. Not much has changed since.

In the 1990s, when the Sons of the Sons of the Sons of the Pioneers were formed, there were about 2,900 people living in Henrietta. It was the kind of place where, at your funeral, they lay your spurs on the lid of your casket. Where your street address is also your last name, because your family has been ranching there so long. You could walk out at night and hear coyotes and train whistles, and the moon was bright enough to cast shadows on the ground.

The band had five members. Wayne and Mike, dyed-in-the-wool Henrietta ranchers, were the funny ones. Lewis—editor of the Clay County newspaper—was the serious one. Eddie was the talent, a former professional musician who had settled for a quiet life as grounds manager for the school district. And Tommy, my father, was the preacher at the Methodist church. I guess he was the face.

They took their name from the Sons of the Pioneers, the Hollywood cowboy group Roy Rogers rode to fame with in the 1930s. The band was supposed to be a joke—the preacher and a group of other notable citizens performing the Rogers classic “Cigarettes, Whiskey, and Wild, Wild Women” at the church talent show. The five of them dressed up in their cowboy hats and bandannas, tucked their bluest jeans into their fanciest boots, and shined up their belt buckles. They sang about smoking and drinking whiskey to a room full of lasagna-eating churchgoers, and hammed it up shamelessly. And that was supposed to be the end of it.

But then, when the evening was over, they got requests for gigs. People loved them, wanted to hear them again. They played weddings and funerals, at the retirement home and the elementary school Christmas pageant. They built a repertoire, ranging from authentic folk cowboy pieces like “Whoopie Ti Yi Yo” to contemporary Michael Martin Murphy songs. Lewis ran off mimeographed sheets of lyrics for them to practice. Wayne and Mike took up the tambourine and woodblock with what can only be described as enthusiastic tenacity. The Sons of the Sons of the Sons played for the Chamber of Commerce, and under the bright lights of the Clay County Pioneer Reunion and Rodeo. At one gig, indulging the allure of their growing renown, they replaced the sweet tea in the prop whiskey bottle they drank onstage with the real stuff. (It apparently came as quite a shock to my dad, the preacher, when he took a big pull in the middle of a song.) They were the hottest thing to hit Henrietta since Quanah Parker.

Of course fame didn’t last. Lewis ran off and got married, which significantly dampened his enthusiasm for the group. They struggled on with a replacement who played stand-up bass. In 1996, the bishop moved my father out to northeast Texas, and the Sons of the Sons of the Sons of the Pioneers were no more.

It is notoriously difficult to get cowboys to talk seriously about anything, much less the songs they sing. When a young John A. Lomax was building the first scholarly collection of cowboy ballads in the 1910s, the only people more resistant to the idea than the Texas academics were the cowboys themselves. Lomax writes that when he attended the Texas Cattlemen’s Convention in San Antonio, in search of new songs, a “belligerent cattleman” told all those gathered: “I have been singin’ them songs ever since I was a kid. Everybody knows them. Only a damn fool would spend his time tryin’ to set ’em down.” Then the cowboys all adjourned “to a convenient bar.”

Even so, I wanted to get the Sons of the Sons of the Sons back together, twenty years after they broke up, to hear about their time as the accidental celebrities of a little Texas ranching town and, see what the music and the experience means to them today. Our conversation was to be fairly high-minded, as I envisioned it. So in November, I gathered as many of the Sons of the Sons of the Sons as I could find and we met up at Wayne’s place, the 2R Ranch in Henrietta.

Lomax claimed that the sources of a folk song were “as mysterious and unknown as the Texas grasses that grow above (an outlaw’s) grave, rustling and whispering in the Texas northers that sweep through them on long wintry nights.” I take myself far less seriously, but I thought if I could keep the questions to a minimum and just listen in as these old friends talked to each other, I could come out with a story. I was incorrect, but it wasn’t because these cattlemen were belligerent. I showed up with two cases of Shiner Bock and the words flowed freely. The problem was something that should have been obvious to me from the start: it was never really about the band.

The Sons of the Sons of the Sons of the Pioneers talked for two hours. Of that, maybe twenty minutes touched on the music they had played. The rest, well, it was what you might expect from people who hadn’t seen each other in twenty years. They talked about church, and preachers who had come and gone. They talked about who had died, who had gotten married, who had gotten divorced. Pictures of grandchildren were shared. There was laughter and good-natured ribbing, and at the end, I brought out my guitar and Eddie took it for a spin. His voice was still bright and strong, surprisingly so. “I still think about that time a lot,” Wayne said, serious for just a moment. “It really was something.”

I have no doubt that the music the Sons played spoke to the people of Henrietta. Not everyone in the town rode and roped, but songs like “Cool Water” and “Back in the Saddle” were part of a cultural self-image that the whole community believed in. The frontier spirit, even today, is a big part of what it means to live in Henrietta, Texas.

But the music, per se, remained largely incidental. Eddie was once a serious musician—he toured, and even recorded an album produced by Texas legend Lloyd Maines. But the rest of the Sons had never been paid for music before or since. Together, they weren’t looking for fame. They certainly weren’t trying to make money from it. Nor were they nursing any artistic or expressive pretenses. They were hardly ever even on key.

Out on the plains of Texas, where a handful of folks came together to cut a living out of the prairie, where there were weddings and funerals and church dinners and birthday parties, music is a fact of life. It comes from amateurs or professionals, from ranchers and preachers and newspapermen. The people who play it perform a service not so different from an undertaker or a city council member. Music happens where people are gathered.

I think the Sons of the Sons of the Sons of the Pioneers would roll their eyes at the notion that music forms itself ex nihilo as a function of community. But for a moment there in my childhood, the heart of the folk tradition was alive and well in Henrietta. Its practitioners taught Gene Autry songs to auditoriums full of fifth graders and took pulls of whiskey in the fellowship hall. Laughed at their own jokes, and solemnly sang “Streets of Laredo” at the funerals of their friends.

I was there for that moment, admittedly minor, yet meaningful nonetheless. As I grew up, and my preacher’s family bounced across Texas, I quickly began to recognize names like Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Willie Nelson, learning the stories of my state’s music. On my father’s desk in the office of whatever church he pastored, there was always a picture of the Sons of the Sons of the Sons of the Pioneers: onstage in a dingy, poorly lit cafeteria, with their sunglasses on and bandannas around their necks, looking like they were having a hell of a time. For me, the image of those five men will always be what music looks like in the flesh.