She's About a Mover

By Alex Harris, Margaret Sartor, and Reynolds Price

Editor’s Note: We are saddened to learn of the death of legendary Texas music writer Margaret Moser on Friday, August 25, 2017. She was sixty-three. Raised in New Orleans and San Antonio, Moser moved to Austin in 1973 and immersed herself in the local scene, which she would become synonymous with as longtime music writer for the Austin Chronicle. In this feature essay for the OA’s 2014 Texas Music Issue, written just after her cancer diagnosis, Moser shares vivid stories from her pioneering career: “A life writing about music wasn’t part of the plan, but then I’d had no plan. I had dropped out of high school, didn’t attend college, had no special training or talent for much, other than a knack for making a place for myself where places didn’t exist. I’ve long joked that I got in through the back door, so whenever I am let in through the front door, I run to the back to see who I can let in.”

PORTRAITS FROM A LIFE SHAPED BY MUSIC

February 1966

New Orleans, Louisiana

In the wake of a glittering parti-colored float populated by masked revelers tossing beads, trinkets, and coins, the high school drumline marched into view a block down Freret Street. Rhythm infused the earth below into the clouds above as the pounding of the skins drew closer. The snare section’s sharp report followed by the toms and bass made the very sidewalk throb to life under my Keds. Preceding the drummers were the flambeaux marchers. This was the spectacle to behold.

They were a half dozen or so young black men, many stripped to the waist in the cool February evening air. Leather holsters around their slim hips held wooden poles aloft, sparking red flares belching gray smoke at the top. They shined with sweat bathing their lean, sinewy bodies, white t-shirts tied at the waist or wound atop their heads turban style, and free-form snake dancing to the primeval beat while balancing their torches under dark heavens.

Five adolescent black girls were walking alongside the flambeaux marchers, dodging the crimson sparks. They were overdressed for their age, but appropriate to the anything-goes carnival tradition. Glistening dark hair teased into curly piles topped with tiny velvet bows, too-tight white sleeveless blouses, pencil skirts, and pointy-toed patent leather high heels that guaranteed blisters the next day. They were the queens of the night, their high sing-song voices chanting words familiar as a counting rhyme as they clapped in time.

Look at my king all dressed in red

Iko iko annay

Betcha five dollars he’ll kill you dead

Jockamo fe ni nay

Their mysterious patois was the currency into the seductive world of New Orleans music, a language of stories and songs to fire the imagination. Who were those girls? What king? Why was he dressed in red? Who was Jockamo?

Somewhere near the French Quarter that year, my father took me to see the Zulu Parade. As we walked, a black man dressed in long robes stood behind a trash can or maybe an oil container, playing it like a drum. Its hollow, metallic echo bounced off the bricks and pavement and vanished in the air. He’d change rhythms in an instant, slow to a hypnotic rhythm, then pick up the pace, smiling all the while, never dropping a beat. I watched him until we turned a corner and the drumbeats faded while still pulsing in my blood.

These images and sounds felt mysterious and unknown, a potent combination to the young and curious. I’d feverishly discuss the meaning of song lyrics, most especially the dirty ones, with anyone who seemed to understand. My neighbor Fielding Henderson, one grade ahead, and his buddy Bobby Wood knew all about the Coasters and Bobby Marchand, Dusty Springfield and Irma Thomas, the Rolling Stones and John Fred & the Playboys, the Kinks and Chris Kenner. They traded 45s and LPs like baseball cards, occasionally deigning to discuss such weighty matters as rock & roll with a deeply uncool but curious seventh-grade girl down the block.

I nursed a teen crush on Fielding, but he had eyes only for an eighth-grade classmate I didn’t know, a bookish girl named Lucinda Williams. Her father taught at Tulane University, as did my father. But when my parents decided to move to San Antonio, Texas, at the end of the summer of 1966, that world vanished.

Bitterness over the impending move to San Antonio assuaged itself through the airwaves, a vibrant mix of hip English blues bands, folk rock, garage rock, and New Orleans favorites filtered through a tinny red Sears transistor radio. Once the Beatles altered my fifth grade life, the radio became a sanctuary during endless summer visits to my grandmother’s house in Port Arthur, Texas. In the night, close to the Gulf of Mexico, came the fabled XERF from below the Mexican border and WLS from Nashville, sometimes WBAP from Fort Worth. Other times the regional stations that dotted Cajun country dominated the airwaves with French music. The ting-ting-ting of the triangle, sawing of the fiddle, and wheeze of the accordion crackled through the swampy darkness until the signal weakened.

From Christmas 1965 in New Orleans until it died while I attended high school, that transistor radio was my constant companion, often connected almost umbilically by an earpiece. I faithfully collected WNOE and WTIX hit lists. On the back of one hit list, the lyrics to “The Rains Came” by the Sir Douglas Quintet caught my eye. They were from San Antonio and Doug Sahm was their leader, I knew from watching Shindig and poring over issues of 16 magazine.

Perhaps Texas wasn’t so bad.

April 1970

San Antonio, Texas

So why did I become a groupie? Rolling Stone trumpeted the rock & roll lifestyle, so forbiddingly glamorous—what girl wouldn’t want to escape the Middle American Dream to be a Sixties sybarite rubbing satin-clad shoulders with rock stars? Los Angeles beckoned in the west like a golden Oz, New York City emanated Velvet chic, Chicago boasted the Plaster Casters. Living in suburban San Antonio felt impossibly provincial compared with those urban Xanadus and my purple, gold, and green memories of New Orleans.

Here there was no Mardi Gras. No going into a bar around the corner to buy po-boys, no horse-drawn carts in the neighborhood selling Roman candy. No sno-cone stand on the corner. No sound of the tugboats on the Mississippi at night. Only newly built houses in the shiny happy suburbs.

But with the emergence of the Sixties underground into mainstream—with our rapidly changing communication and technology, and a youth culture that dominated the media—Texas rock & roll distilled its Buddy Holly and r&b roots into bombastic and influential garage rock, ranging from Holly-influenced rebel anthems such as “I Fought the Law,” by El Paso’s Bobby Fuller Four, to the Sir Douglas Quintet’s Tex-Mex tune “She’s About a Mover,” to the Corpus Christi psychedelic pioneers Bubble Puppy’s “Hot Smoke and Sassafras.” The 13th Floor Elevators laid out the plans for psychedelia in Austin in their first album, but the ethereal Easter Everywhere took on a distinct San Antonio edge when the band’s membership shifted. And in one short four-year arc, Doug Sahm repositioned the Sir Douglas Quintet from faux-English mods to progenitors of outlaw country with “Mendocino.”

More importantly, rock & roll bands were eminently accessible. A local club called the Teen Canteen featured local groups from around the city, around the state, and occasionally national acts. Some developed into big-name acts as when Houston’s the Moving Sidewalks morphed into ZZ Top. These were actual bands you could meet and see week after week. Maybe even go to school with.

By the summer of 1969, enterprising local hippies ran hugely popular Sunday rock concerts at the Sunken Garden Theater in Brackenridge Park, where a youthful Christopher Cross honed his estimable guitar chops, and a group called Homer turned a country songwriter named Willie Nelson into a rock composer by electrifying “I Never Cared For You” on 45. Meanwhile, San Antonio was the first stop for touring bands like Led Zeppelin, the Allman Brothers, Janis Joplin, and Jimi Hendrix, who played there three times in his short career and whetted the Alamo City’s celebrated appetite for hard rock. This was all heady stuff for a teenager for whom rock & roll was the chief salvation from adolescent agonies of bad skin, worse grades, and a deep, echoing sense of alienation from the rest of my high school milieu. Redemption came through stacks of spinning vinyl and three minutes of freefalling into the promise and lure of lyrics and rhythm.

But I wanted to be inside the secret heart of rock & roll. After I gave up my virginity in a park following a March 1970 Jefferson Airplane concert, I discovered that luck really was the mere chance of preparedness meeting opportunity, that hanging out behind the Municipal Auditorium or Convention Center Arena in the afternoon during soundcheck almost guaranteed a chance to meet the band, score backstage passes, watch the show from the wings, and ride back to party heaven at the hotel in a limo. Yet San Antonio also held musical secrets like a seasoned poker player. It had been a major stop on the chitlin’ circuit and with jazz and blues bands in the Thirties and Forties. Endemic in the city was the exotic music from a couple hundred miles south: mariachi, orquesta, conjunto, Tejano, norteño, and infinite variations. Robert Johnson recorded the first of his only two sessions in the Alamo City.

My high school class attended the World’s Fair in San Antonio. On the way, we passed a black man smiling as he pounded rhythms with his hands on an oil drum. I stopped. I’d seen the same man at Mardi Gras in New Orleans a few years before. He stayed around San Antonio for a while after the fair closed, long enough for me to ask the record store clerk at the mall who seemed to know everything and disdained those who did not.

“Who’s that guy playing trash cans downtown?”

“That’s Bongo Joe,” the clerk begrudgingly allowed.

June 1974

Austin, Texas

The notion that Austin in the early 1970s floated under a hazy violet crown of non-traditional country music, pot smoke, and cold beer is patently true. Nashville and Los Angeles also shared in the progression of country music away from the slick, string-laden countrypolitan sound of the Sixties, but Austin captured its share of the cosmic cowboy mythos with no industry to support it.

If there was one contributing factor in Austin’s emergence as a music mecca, I believe it to be this: the booking policies of the Vulcan Gas Company (1967–70) and the Armadillo World Headquarters (1970–80) established and promoted Austin as an eclectic whistle-stop in the middle of heartland Texas with an appreciative audience that was open to all genres of music. Accompanying these shows was an outpouring of concert poster art that produced some of the rarest works of the era and, for more than a dozen years, illustrated the growth, depth, and breadth of the scene. Interestingly, Texas music was also supported by a mid-Sixties migration to California—a Texodus, if you will. Behind the scenes of the Avalon Ballroom, Rip Off Press, KSAN, and other hip Bay Area entities were those who’d fled the Lone Star state’s oppressiveness for the land of organic milk and wild honey.

That West Coast presence reaffirmed the credibility of Austin as an oasis of cool in a state sporting a black eye over the assassination of President Kennedy. Having a bunch of go-getter Texans smack in the middle of the Summer of Love made for wild creativity with a Lone Star spin. Any San Francisco soundtrack of the era would have to include Janis Joplin, Johnny Winter, the Sir Douglas Quintet, and the 13th Floor Elevators, among others.

That counterculture zeitgeist echoed a couple thousand miles away in Austin, where many of the Texpatriates attended UT before fleeing to the West Coast. It came in the form of underground press and progressive radio stations like The Rag and KOKE-FM, organic food stores and head shops, cheap housing and cheap gas and cheap covers at the growing number of clubs popping up, and the sense that Austin was the place to be. And music threaded the lifestyle. Nineteen seventy-two delivered Willis Alan Ramsey’s self-titled LP and Michael Murphey’s Geronimo’s Cadillac—and 1973 saw Murphey’sCosmic Cowboy Souvenir, Willie Nelson’s Shotgun Willie, Jerry Jeff Walker’s hugely popular Viva Terlingua, Asleep at the Wheel’s Comin’ Right At Ya, and Doug Sahm’s essential Doug Sahm and Band grand-slam Nashville and Southern California and stake Austin’s claim as the capital of progressive country music. And 1973 was the year I moved to Austin, nineteen years old, right in the middle of the good old daze.

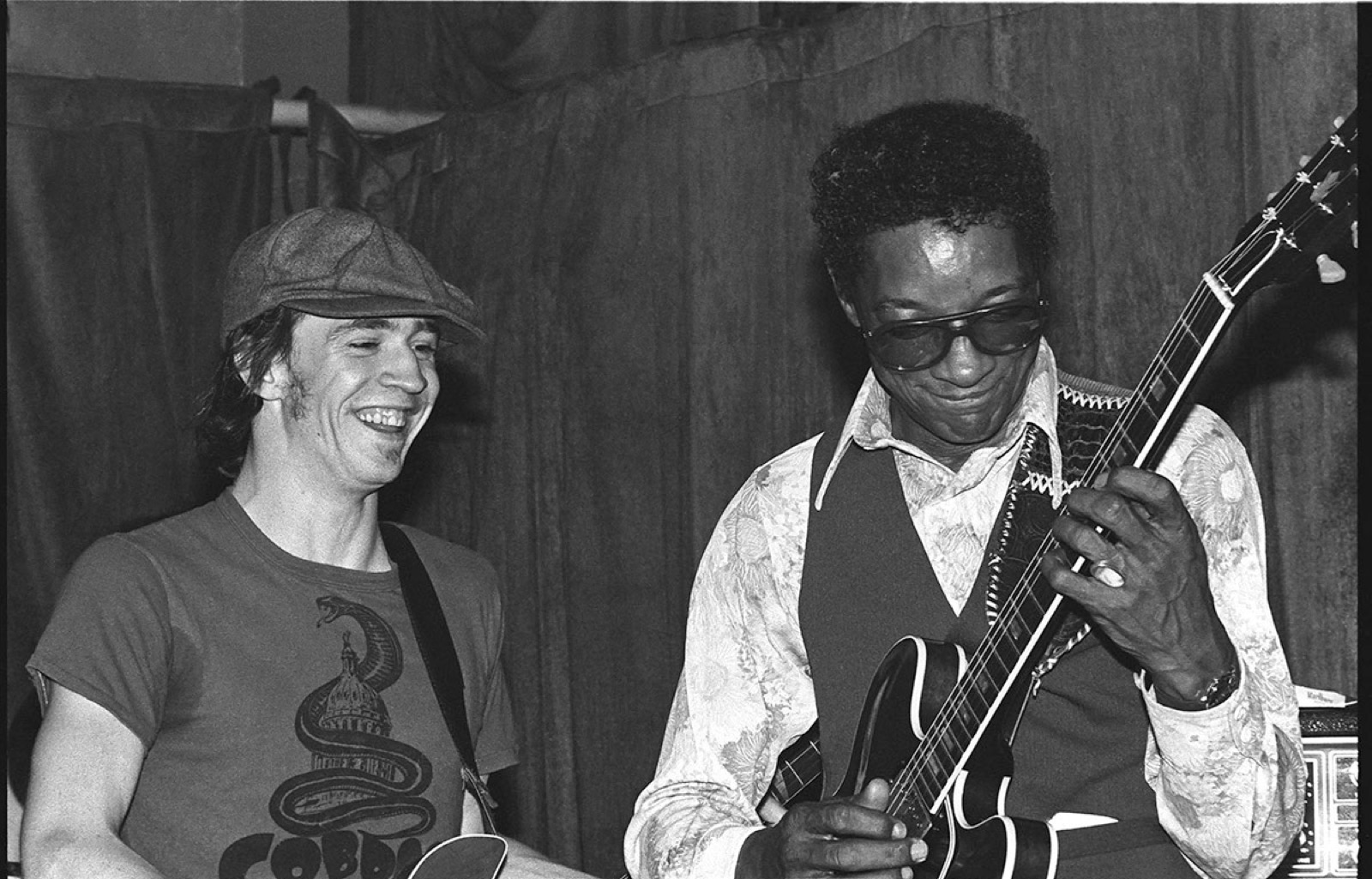

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Hubert Sumlin at Antone's Blues Club, 1978 © Ken Hoge

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Hubert Sumlin at Antone's Blues Club, 1978 © Ken Hoge

May 1976

Austin, Texas

At twenty-two, my future felt amorphous. My beloved father committed suicide in 1974 just after I’d turned twenty. It took a while for the grief to work itself out and drugs left me comfortably numb. In those days, work was merely a way to pay for going out, my chief occupation. By the time Bob Dylan and the Rolling Thunder Revue landed in Austin in May of 1976, I hung out with not just bands, but coke dealers, pot dealers, and other unsavory characters that inhabit rock & roll’s shadows. Texas was no piker in the drug trade, as Rolling Stone noted in its “Dope, Death, and Dirty Dealing in Texas” article of September 1974, and Austin’s cachet as a musical oasis practically multiplied when Rolling Thunder decided to camp out for a few days.

The closest nightclub to the Revue’s homebase of the Driskill Hotel on 6th Street was a cavernous blues club less than a year old called Antone’s. It was one of only a handful of clubs in the area aimed at young people; the rest were working-class beer joints and Mexican bars that didn’t allow women. Sixth Street bore no resemblance to the tourist destination it would become, but the nightly parade across the street of Dylan, Joan Baez, Roger McGuinn, Joni Mitchell, T-Bone Burnett, and Mick Ronson, among others, set a new standard of celebrity cool for the fledgling club.

Just hanging out on the fringes of the Rolling Thunder Revue during their days-long stay set me on fire. I spied an ad in the local alternative biweekly, theAustin Sun, advertising for someone to clean the offices. The pay was pittance but I left a straight job with benefits to clean the bathroom and sweep the offices of a newspaper I’d admired for its stories. The staffers were mostly about ten years older than I was—though some, like music editor Bill Bentley, were closer in age. This did nothing to endear me to Bentley, whom I pestered endlessly with gossip I’d picked up from the local bands. Occasionally, he’d incorporate information I’d given him and I felt vindicated, purposeful. My luck shone when preparedness once again met opportunity in my life.

“Who’s writing the Backstage column this week?” editor Jeff Nightbyrd queried at a staff meeting. As Jeff Schero, he’d been national vice president of the SDS and earned his radical politics editing RAT magazine in New York City in the Sixties. Managing editor Dave Moriaty had been a founder of San Francisco’s underground comics publishing house, Rip Off Press, in the Sixties and early Seventies.

No one replied.

“Spirit is playing at the Armadillo this weekend,” I said, “and I know Randy California.” It was a half-truth, but I knew how to get to a band, and this time it would be as a journalist, however novice. I got the gig and kept the column.

I interviewed Randy California after the show as he lay in the large bathtub of the Driskill’s spacious bathroom. I was naked except for my notebook and pen.

March 1980

Los Angeles, California

My girlfriends and I left the Whiskey A Go-Go, driving down Sunset Strip with Christopher Cross’s “Ride Like the Wind” on every radio station, it seemed, and headed to the Tropicana Motel for late-night partying with the John Cale band. Cale himself was off being interviewed by Richard Meltzer, whom he accused of being a CIA operative, though later on he burst through the door, late to the party, coked up and rowdy. I smirked at him and he lurched toward me, heaving me over his shoulder and carrying me off to my room.

I retired from being a groupie twice, the first time in 1971, a scant few months after embarking on it in San Antonio, and continuing through my brief stay in Seattle. I slid back into groupiedom in Austin during the onset of punk rock, because English rockers were just too cool to resist, and retired again in 1984. Both departures involved a committed relationship, and after I married a second time in 1984 I never went back.

The second time around I had self-imposed rules: touring bands only, no locals. That political choice kept me in good standing with the numerous wives and even more plentiful girlfriends. I’d stayed in contact with many musicians, and played utterly chaste hostess to bands like Cowboy Mouth, who spent more than a few nights sleeping in my various Austin abodes, which Candye Kane always dubbed The Marga-Ritz.

Here’s God’s truth about it: being a groupie wasn’t about sex, it was about access. I wanted to live in the stage life, dazzled by color and sound, constantly in motion, driven by excitement and power, loved by the stage lights, part of the story. It intoxicated me to participate in the most benign, basic aspects of rock & roll (that would pay off in the Eighties when I performed with a show band) and to inform my knowledge of the day-to-day business of touring. I learned by observation about booking hotel rooms and flights, arranging transportation, scheduling interviews and appearances, feeding crews, opening bands, wardrobe concerns, all the while thrilled with the insider knowledge of how things worked. I was thirty, way too old to compete, and with eight years of writing behind me, my lifelong desire for access into the world of rock was occurring on a level I never imagined.

Yes, the sex had been fun, hot, druggy, and free (except for the occasional trip to the clinic), but I never wanted to be a musician—I wanted to tell people what I’d heard and seen. The sex was almost incidental.

Even with Iggy Pop.

1986

Austin, Texas

By the time the Austin Sun finally set in the late Seventies, its vibrant core of writers and talents had largely migrated to Los Angeles, and Austin was without a regular alternative paper. During the late spring of 1981, rumors began to float about a new biweekly in the works. A couple of communications school students known for their critical opinions and cultural actions helmed the publication and gathered other like-minded writers. The publisher, Nick Barbaro, had been arrested during the landmark event known as the Huns bust, in which undercover cops arrested an art punk band and onlookers. The editor, Louis Black, helped galvanize the local film scene in a way that led to the current crop of filmmakers—people like Rick Linklater, Robert Rodriguez, and Mike Judge. Jeff Whittington, the music editor, was one of my best friends. They needed a gossip columnist. How could I refuse? I wrote a column for the prototype issue and debuted with the first issue of the Austin Chronicle on September 4, 1981.

Punk rock had arrived in Austin not long before the Sex Pistols infamously invaded San Antonio at Randy’s Rodeo in January of 1978. It emerged in England about the time a local crew of young white players, including the brothers Vaughan, incubating in the Texas blues, burst forth with new blood and new commitment to the form. With progressive country on the wane but with a resurgence of folk via singer-songwriters like Townes Van Zandt and Lucinda Williams, Austin in 1981 felt as musically vital as it had in 1973.

At the Chronicle, we music writers assumed our gatekeeper posts with utter abandon and dedication. We resided after dark in theaters, clubs, stages, stores, and on the street, witnessing the changing face of Austin, even imprinting it indelibly. It was our duty to be on the scene nightly. Miss a night and you might miss history being made.

In mid-1986, musician-writer Jesse Sublett and I sat at a cocktail round in the dim afternoon light of the Continental Club as the True Believers set up for a show. Neither of us were talking much, just watching the come-and-go process. Austin music felt poised for a seismic post-post-punk musical shift of some sort. Bands like Timbuk3, Zeitgeist (later the Reivers), and the Wild Seeds stood in direct contrast to Daniel Johnston and Dino Lee & the White Trash Revue, but Austin supported them all with equal fervor. So did MTV, who’d sent their show The Cutting Edge to capture it all.

Alejandro and Javier Escovedo crossed the stage and picked up their guitars to check them, followed by Jon Dee Graham, who strummed a twangy chord into the club darkness.

“I love their jangle and harmonies,” I sighed to Jesse.

“Eh. They’re too. . .” Sublett paused for a moment, and sort of sneered, “new sincerity for me.”

I noted and printed the phrase in the Chronicle: New Sincerity. The term served as a catchall and stuck in the local, then the national, lexicon.

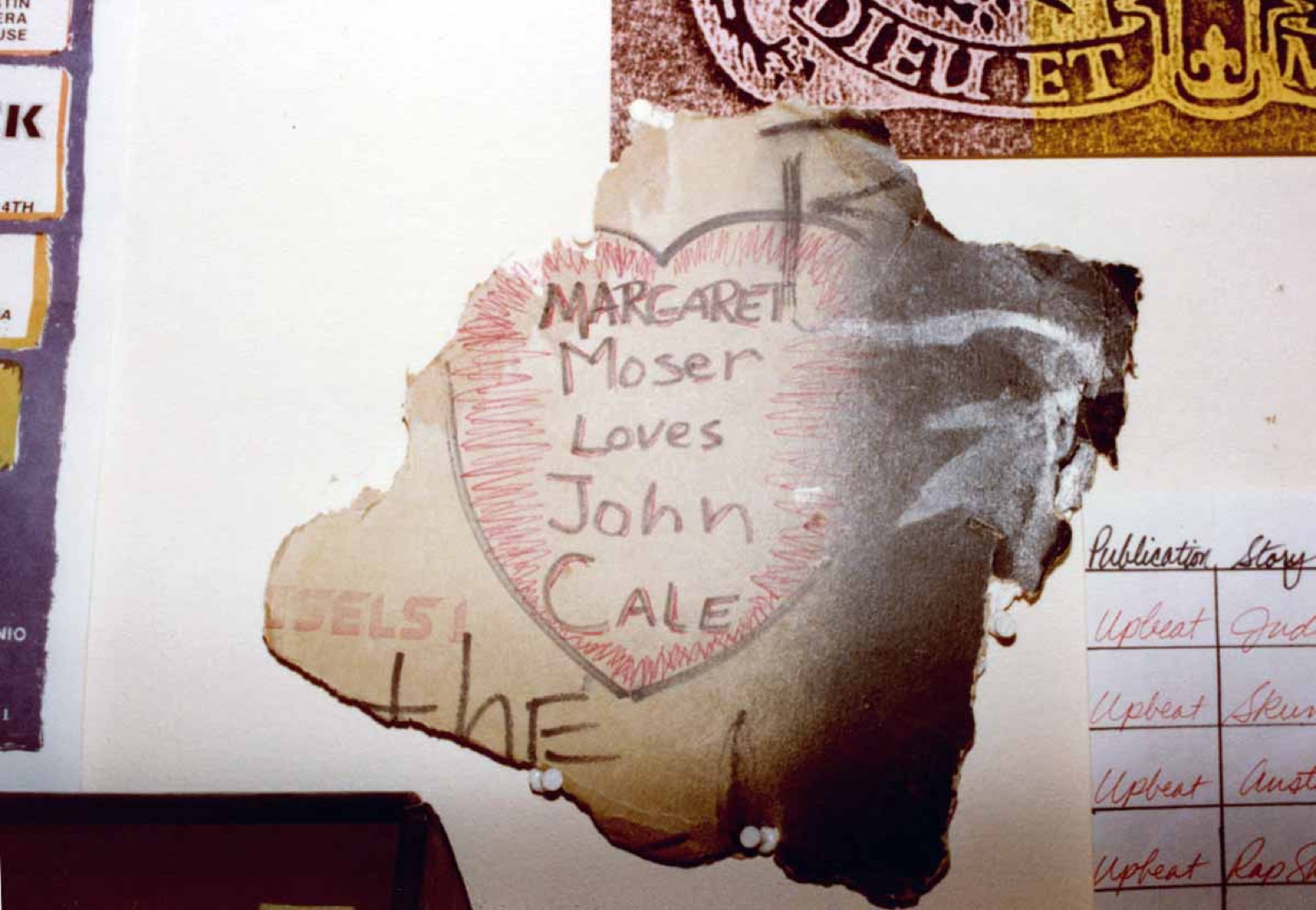

Graffiti at Raul's, 1981 © Ken Hoge

Graffiti at Raul's, 1981 © Ken Hoge

May 1990

Hilo, Hawaii

The Merrie Monarch Festival, Hawaii’s premiere hula competition, was packed with audience members facing west toward the sun setting behind Mauna Kea. These were the dancers of ancient hula, wearing skirts of glossy green ti leaves with wristlets and anklets to match, not the mannered performers ofhula a’uana or modern hula, with their Mormon-inspired muu-muus and more familiar gestures. Hula kahiko fascinated me, particularly when the chanting is done by women, whose sonorous voices were sometimes practiced at Kilauea volcano near the edge of the Halemaumau crater.

I’d been in Hawaii since October 1988, when I moved with my tattoo artist husband Mike Malone, better known by his nom de tattoo Rollo Banks. He’d worked under Sailor Jerry and inherited his Chinatown tattoo shop after Jerry’s death. But Rollo’s business was in Hawaii, mine was not. No alternative paper, weekly or otherwise, existed in the fiftieth state then, so I went to work editing tourist magazines. It afforded the occasional chance to promote bands I knew or liked, but my first lesson was that not every city has a market for original rock & roll the way Austin did.

Finding cover bands was no challenge; they thrived in hotel lounges and entertained Japanese tourists by the busload. Harder to find was the real thing—the falsetto-voiced singers like the Pahinui family or slack key greats like Ledward Kaapana. Yet Nashville expatriate and Hawaiian steel master Jerry Byrd could be found playing in Waikiki’s Pink Palace, the Royal Hawaiian Hotel. Now and then, bands I knew played the islands—Timbuk3, Poi Dog Pondering, the Fabulous Thunderbirds. It was always bittersweet, and they made me deeply homesick.

I’d packed up our house and belongings and shipped them to Hawaii via U.S. mail and a moving company, but I was a poor fit with paradise. It was gorgeous, the weather balmy and bucolic, the food exotic and delicious. My best friend FedExed me frozen gallons of salsa from my favorite Mexican restaurant and cassette tapes of Paul Ray’s Twine Time program on KUT FM that made me cry, I missed Austin so much.

Hawaii was home for nearly two and a half years before I returned to Austin in June of 1991. I did find many things to love about the islands, not the least of which was the local phrase “talk story,” which meant to set a spell and chitchat. I talked story with neighbors in Chinatown, especially the two women who ran a lei stand on Maunakea Street below our high-rise apartment. They’d sit daily in the compact open-air shop, fingers nimbly threading the fragrant blooms of all colors and sizes clustered in their laps, from the tight, creamy buds of pikake to the pastel-petaled plumeria and audaciously grandohai ali’i. One of them, it was whispered on the street, had been the mistress of a wealthy Chinese man who set her up with the lei stand when she grew old.

And there was the beach. Every Saturday morning on the windward side of Oahu my friend Lisa and I stopped at Bobby’s in Waimanalo for a six-pack of Dos Equis (my choice) and dried squid and shrimp chips (hers). Maybe we’d drive around the island later, maybe go see Oriental Love Ring or the Pagan Babies that night. Maybe fly to Maui the next weekend. I wondered how to translate “mañana” into Hawaiian.

Ha`ina `ia mai ana ka puana is the line that begins the final verse of traditional Hawaiian songs. It can be interpreted as “and the story is told.” The words resonate with me even now, those soft days of blue skies and bluer water so many years gone.

1996

Nashville, Tennessee

These were years of going on the road in earnest, in search of stories that truly reflected the business of being a musician. I was at Lucinda Williams’s house, the engine running on the bus outside as she prepared to leave Nashville for a gig in Knoxville.

Lucinda and I didn’t know each other when we both attended McMain Junior High in the 1960s in New Orleans. We started hanging out in 1981 and knew each other nearly fifteen years before we discovered our parallel lives and how we were connected by the chance happening that her boyfriend was my neighbor. That wasn’t the tie that bound us, though it further tightened the bond. I’d been present in the room with her one-time boyfriend/manager Clyde Woodward when he died. Theirs had been a tumultuous relationship and Lucinda had married and divorced in the interim, but Clyde’s influence was so profound that when his deterioration from cirrhosis of the liver reached its final stages in August 1991, Lucinda jumped on a plane from Los Angeles to see him one more time.

Clyde died as Lucinda was in transit and she didn’t get to say goodbye, but I could tell her what it was like: Clyde Woodward’s life slipped away as I sat on one side of the bed and held his hand, playing a cassette of lowdown blues songs for him in those long last moments.

The Nashville trip forged our bond closer. At an Antone’s gig, Lucinda had poured her heart out at what fans and critics alike would regard as one of her finest shows ever in Austin. Lucinda turned around after dispensing with the hour-long queue of well-wishers and friends. She had that wild look in her eye that a little likker’ll give you. Her face broke widely into a smile of great mischief and she bounced next to me on the couch as we tumbled together in a tangle of black clothes, silver jewelry, and giggles.

We hugged and she whispered in my ear, face pressed into my hair, “Did you ever fuck Clyde?”

“What? No!” I cried, pushing her away and sitting up. Holding her angular jaw between my hands, I made her look at me. “Never! Not even close—we were really and truly great friends! Drug buddies!”

“Well, I did fuck him, and he died with you, and that’s the most connected you can be to a person,” she mumbled. “He comes to me in dreams, sometimes. In one, he’s whipping me. In another, he’s trying to pull me, make me go with him.” She pulls away. “I have to tell him, no. Go away, get away from me. And then he looks all hurt, like a little boy.”

Suddenly, I missed Clyde terribly. I put my arms around Lucinda and held her like a child.

November 1996

Austin, Texas

On a crisp November evening of 1996, Doug Sahm stood beside me backstage at Liberty Lunch as we watched Son Volt. Sahm’s arms were folded against his chest, his sculpted face in profile to me, eyes fixed on the band. Now and then, he’d turn and bark something to me, but the band was what had his attention.

“They’re good kids, good band—I’m Jay’s hero, man!” Doug always made me grin.

Sometimes, I couldn’t believe the good fortune life presented me, the luck of the deal, like having Doug Sahm consider me a buddy. He was a national rock star to me in my teens, a palpable presence in San Antonio when I’d moved there in the Sixties, a leader in the progressive country movement, the man the late Chet Flippo called a “walking, talking Austin Chamber of Commerce.” Hell, he’d been on the cover of Rolling Stone twice!

We’d gotten to know each other many years before at Soap Creek Saloon. He came to my first wedding, and for many years he was one of the go-to musicians when I needed an Austin Music Awards set put together. I took a motherly interest in his three children. Though Doug was extraordinarily gregarious with everyone, he seemed to give me a few extra points for being from San Antonio.

It’s possible Doug Sahm was the ultimate Texas musician. From steel-playing child prodigy who literally sat on Hank Williams’s knee at the Skyline Club to local radio and club star as a teenager, to a national hit maker masquerading as a British popster, to spearheading progressive country and then forming the cross-cultural, Grammy-winning Texas Tornados, there wasn’t a genre of music he hadn’t conquered. His death almost exactly three years later left a Texas-size void in the heart of the Lone Star state. But on that November night, Sahm’s spirits soared as Son Volt played on the Liberty Lunch stage. Jay Farrar would occasionally glance his way with a nod, biding his time before calling Sahm to the stage to encore on “Give Back the Key to My Heart.” Sahm anticipated this, turning as he headed toward the stage steps and assuring with no modesty whatsoever, “These guys love me!”

And they did.

August 2008

San Antonio, Texas

August in San Antonio, the bear of summer in South Texas. Sitting in an SUV parked behind the compact Saluté bar on North St. Mary’s Street was Steve Jordan, sometimes called El Parche for the patch he sports over one eye. Jordan’s instrument of mass instruction is accordion, the traditional instrument he steered into very untraditional rock territory, thus earning comparisons to Jimi Hendrix.

He patted the velvet vest over the midnight-blue puff-sleeved shirt he wore, its swirling pattern a reminder of Jordan’s old-school upbringing when it comes to dressing the part. The eye patch gave him instant notoriety and mystique. The look was part of the Mexican culture of music, the folk, the modern, the cholo, the pachuco. He took the look and gave it the same treatment as he did the accordion.

His expression was puro Steve Jordan, a poker face with a touch of the trickster. In the shadows of the front seat, his gaunt bones were copper, lined in bronze. Backlit by the blue-white streetlights, he reclined and rested his head against the seat, staring from beneath one iguana-lidded eye. Suddenly, he’s Chac-Mool, one of the supine Mesoamerican stone sculptures found by the Mexican pyramids around Chichen Itza and other spiritual Mexican hot spots. Carlos Castaneda called them representations of dream-guards, the ideal protectors of any chosen person, idea, way of life. Steve Jordan reclined perfectly still, then his face split into a grin. He was ready to talk.

The sweltering night was magical: I interviewed the often reticent Jordan, who was dying of cancer. I met a photographer and artist named Joan Frederick and knew we would be friends; of the two gentlemen I saw on the patio, one was New York Times writer Jeremy Sparig, the other a local musician who introduced himself as Manny Castillo.

Manny and I bonded instantly. He was the drummer for Snowbyrd and read my “Browner Shade of Black” story about Chicano soul in the Chronicle the year before. Now, he wanted to talk. “Everything I do is about my people’s music. Even my hat and shirt are in tribute to my uncle.”

Manny continued to regale me with tales of San Antonio’s West Side and how the music was distinguished by twin saxophones and Mexified rock & roll rhythms. I was thrilled, and filled with a passion for the sound. I saw Manny perform the next night, but he was busy playing rock star and I had to head back to Austin in the morning to make deadline. We’ll catch up soon, I told him. Soon, he agreed. Soon never came. Manny Castillo was diagnosed with inoperable cancer scant weeks later and died the following January. His passion for the music stayed tattooed on my heart. Steve Jordan died in 2010. The following year, the Tejano Conjunto Festival asked to reprint “Chac Mool,” the Chronicle’s Steve Jordan story, in their official program. I was elated. I got it right by San Antonio.

Jerry Jeff Walker, Roky Erickson, and Doug Sahm at Gemini's Club (soon to become Raul's Club)

Jerry Jeff Walker, Roky Erickson, and Doug Sahm at Gemini's Club (soon to become Raul's Club)

for Margaret Moser's twenty-third birthday party, 1977 © Ken Hoge

April 2011

Clarksdale, Mississippi

Pinetop Perkins died, necessitating a drive to Clarksdale, Mississippi, through the night. The bigger, more lavish funeral had been held in Austin, but Pinetop—once my neighbor and ever my friend—was bound for Mississippi in a casket to a hometown service. That was the one I wanted to attend.

Having Pinetop Perkins as my neighbor had been an unexpected joy. He lived two blocks away, and when I’d stop in to see him the visit usually ended with Pinetop at the piano, playing a little something as I was on my way out the door. My proximity also resulted in phone calls such as this: “This Pinetop. Would you go to McDonald’s and get me a Big Mac and apple pie, mmm-hmmm.” For Christmas that year, I gave him a McDonald’s gift card.

It was a small service on a Saturday morning. Joe Willie “Pinetop” Perkins lay in a casket at the Century Funeral Home on Ashton Avenue in a dusty Clarksdale neighborhood, his final appearance on Earth. Today was a “homegoing” celebration, according to the program. The lid was open.

Mourners gathered and stopped to remember, pay respects, tell a tale, take photos, tap the casket, dab their eyes. Pinetop’s hands were folded, and beside him lay his walking stick with the engraved brass nameplate showing. A red-and-white peppermint rested between his thumb and index finger. On a table beside the casket were sprays of cardinal-red roses and snow-white lilies, a photo likeness chosen to commemorate him, and a neatly displayed McDonald’s bag, presumably containing a Big Mac and an apple pie. Mmm-hmmm.

The honors continued with chitlin’ circuit singer Bobby Rush, fresh from his appearance with Pinetop at Antone’s during SXSW just weeks before. “We may not like this, but if we quit, we don’t get hamburgers,” Rush recalled Pinetop’s lecture about playing out a bad gig. Eden Brent pounded the piano next.

Up stepped Dorothy Moore, whose 1970s soul serenade “Misty Blue” still commands attention. Moore sang “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” humming deeply in the middle. “My grandma always said it was okay to moan,” Moore assured the crowd, “because the devil don’t know what you’re talking about when you moan.”

The presiding minister, Mayor Henry Espy, requested we leave the service in pairs, singing “When the Saints Go Marching In.” Two by two, we paraded into the Mississippi sunshine.

“I don’t know if I can tell a lady what he and I talked about.” A friend of Pinetop’s named Red looked over his black-rimmed glasses sternly, car keys jingling in his hand, Sunday suit shining as we moved toward the tent over the burial site.

“That’s okay,” I assured him. “Pinetop once took me by the hand and said, ‘I write songs about ladies your size.’”

Red guffawed and slapped the roof of a blue car he was passing: “That’s him! You did know him!”

After brief consoling words, the services concluded and the casket lid was closed. The creak of the casket being lowered cut through the low murmur of mourners. The minister cleared his throat. “For anyone interested, this is a pine casket.”

“And this,” declared Mayor Espy, hand resting on the rich, honey-colored wood, “is a Pinetop.”

August 2011

Austin, Texas

At age eighty-one, Shirley Ratisseau came back into my life in 2011 and brought Robert Johnson with her.

She was a distinct memory for me, a habitue of Soap Creek Saloon and the One Knite among others in the early Seventies, but Shirley Ratisseau was more than living Texas music history with eye-popping stories to tell. She blazed trails by blurring the distinctions between black and white music communities, and not just in Austin, but everywhere she lived.

As a singer, she crossed paths with Duke Ellington, the Rolling Stones, T-Bone Walker, Mance Lipscomb, Billy Eckstine, Albert Collins, Count Basie, and countless other blues and jazz legends. Her family was built out of tragedy and flouted racial mores of the day on the South Texas coast. Her experience led her to a teenage guitarist named Stevie Vaughan, whom she recorded and mentored in the early Seventies.

Shirley is not well-remembered by many of the young people she mother-henned, but she’d left her imprint indelibly. In May of 1974, Chet Flippo reported effusively on Austin’s cosmic cowboy scene in a feature article for Rolling Stone. In a letter to the editor signed under her married name, Dimmick, she took Flippo to task for ignoring a plethora of young blues players and displayed acute observation of guitar players who would spearhead the Eighties blues revival.

“‘Austin: The Hucksters Are Coming’ failed to mention that Austin boasts the finest blues and r&b guitarists anywhere—Jimmie and Stevie Vaughan, Mark Pollock, Denny Freeman, W. C. Clark, and Matthew Robinson have such talent it is beyond words,” she advised the world at large. Even so, her name has slipped through time’s back pages. That’s important because memory can be tricky, and among the buried treasures of Shirley Ratisseau resides a bit of history to send music scholars scrambling to their computers: When she was a little girl, Shirley Ratisseau met Robert Johnson.

The life of Robert Johnson ranks among the most mythologized in music. From his largely undocumented twenty-seven years on earth springs rock & roll’s infamous supposition of selling one’s soul to the devil for musical success. What is fact is that during the year Ratisseau cites, in November 1936, Johnson made his best-known recordings with Don Law in San Antonio. In June 1937, in Dallas, he completed a second batch of songs, twenty-nine total. By the next August, he was dead. Poisoned, maybe.

Also documented is that during the 1936 San Antonio recording dates, Johnson was arrested for vagrancy and beaten while in custody. Law, who produced both sessions, rented a room in a boarding house for him while the songs were being recorded and sprang him from jail.

What did Robert Johnson do between November 1936 and June 1937?

Shirley Ratisseau’s account of meeting a young musician her family described as “ill,” “sickly,” and in a state of physical disrepair, as though he’d been roughed up, is beyond tantalizing. Given the Ratisseaus’ reputation for racial tolerance and welcome at the Jolly Roger camp, it’s entirely possible Johnson got word that a few hours south of San Antonio, on the coast, he could rest and recuperate. And fish.

In Shirley Ratisseau’s memory, Johnson showed up during Thanksgiving. At age six, she regarded him as young, and they often fished together, even composing a song about it. Johnson appeared to like the song they came up with, and prevailed upon Shirley’s mother to write down the lyrics to “Fishin’.”

This curious bit of minutiae felt vital and important, so I prevailed on my music editor Raoul Hernandez to let me tell this story, promising that this unknown woman would captivate. He agreed and we published “The Girl Who Met Robert Johnson” in August 2012. When Johnson biographer Elijah Wald posted that he believed the song was Robert Johnson’s, it again felt like a victory, a story affirmed. Shirley died seven months later.

March 2012

Austin, Texas

With the exception of the years 1983 and 1989–91, I directed the Austin Music Awards for the Chronicle. The event trundled along for four years, recognizing the quirky variety of Austin musicians as voted by the Chronicle’s readers. We even booked it on a Thursday so more of the club workers and bands could attend. In 1987, however, the show moved to a Friday night to help bulk up a debut rock & roll symposium named South by Southwest.

Until then, the Music Awards remained a local event, but now we were the kick-off event for a rapidly growing and prestigious music conference. Suddenly, we had a curious national audience, some of whom were deeply interested in who the hot local acts were. This double whammy gave us an unexpected cachet that suddenly made the show attractive to play. In 1993, on a January deadline night at the Chronicle, Gibby Haynes of the Butthole Surfers called.

“Margaret, book my new band for the Awards. It’s called P and Johnny Depp is in it.”

“Gibby,” I said as though he were five years old, “I hire real musicians to play.”

Haynes was silent for a moment. “Bill Carter is in the band.” He cited the songwriter who’d penned some of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s hits.

“You’re hired.”

And so the Awards show began to develop a uniquely Austin edge to it. It had always been Austin-centric by circumstance, but I started to realize the show was in a position to make history with offbeat pairings, all-star acts, and surprise guest appearances.

Roky Erickson has always been dear to me: his tenure with the 13th Floor Elevators completely levitated my teenage soul. Though heartbreaking to watch his mental decline, it was gratifying to see him get help and support and pick up his career again. Texas Monthly set the lead of a story on Erickson at an Awards show that he was famously ill-prepared for and I’d been pissed about ever since. By 2006, Erickson was lucid and performing again with a variety of bands, and I booked him for a comeback gig with his old compadres the Explosives.

It was a successful performance for Erickson, who’d already begun working with the Black Angels. I wanted to see lightning strike twice—his appearance had deservedly garnered great press for him as well as us—so I invited him back for the 2008 show. I batted around ideas about who to pair with Roky with Chronicle columnist Chris Gray, who casually responded, “Why don’t you just put him with Okkervil River? Will Sheff loves the Elevators.”

Although the actual performance was unrehearsed and raw, the recording as a result of the Awards set completed a kind of symmetry for me with Roky Erickson. Something the Chronicle gave me a chance to do gave Roky a chance to do something too. It felt like the happy ending of a fairy tale.

The tales of my tenure with the Music Awards are too many to tell here, only that during SXSW 2012 Alejandro Escovedo brought Bruce Springsteen out as special guest, and by any measurement, having The Boss play your show feels incredible. That balanced out having Robert Plant get in my face about our typically lo-fi production values. Springsteen, by contrast, was gracious and charming, and behaved as though it was his privilege to play.

I retired from the show in the spring of 2014 and was honored in a finale by Shawn Sahm, Augie Meyers, Jimmie Vaughan, and dozens upon dozens of musicians, all singing along to Doug Sahm’s “She’s About a Mover.” It couldn’t have been any more fitting.

Margaret Moser 1979, Punk Poster Show at Amarillo World Headquarters © Ken Hoge

Margaret Moser 1979, Punk Poster Show at Amarillo World Headquarters © Ken Hoge

August 2014

San Antonio, Texas

On a cold February day in early 2013, I told my boyfriend and my mother that something was wrong with me and I needed to go to the emergency room. I went into surgery the next morning and upon recovery was given a terminal diagnosis of Stage IV colon cancer. That quick, that fast. It wasn’t traumatic in the way you imagine. Instead, inside my head, wheels were fast-forwarding.

It’s a cruel luxury to know death will come soon, but it’s a bizarre comfort to know how it will likely come. For me, chemo is really just one big Whack-A-Mole game I’ll play until I get tired of keeping the cancer at bay or the illness simply takes me over. Once I stop, the clock begins ticking louder and faster. Yet being ill afforded me the chance to step out of the pressure of growing old in a field where few women ever get this far, and away from the threatened print medium I have loved.

A life writing about music wasn’t part of the plan, but then I’d had no plan. I had dropped out of high school, didn’t attend college, had no special training or talent for much, other than a knack for making a place for myself where places didn’t exist. I’ve long joked that I got in through the back door, so whenever I am let in through the front door, I run to the back to see who I can let in.

The dire cancer news allowed me the freedom to retire from the newspaper at age sixty, take my savings, and spend my last years as I choose. In the summer of 2014, I sold my house just outside Austin and much of my eclectic rock & roll collection.

I almost moved back to New Orleans, but I am a true Texan—as much as if I’d been born in the Lone Star state instead of in Chicago. Inspired by the Austin venture, and with stellar help, I had founded the South Texas Popular Culture Center in San Antonio in May 2012, a scant eight months before the reaper breathed down my neck, so perhaps it was fait accompli. Forty-one years to the month after I moved to Austin, I moved back to San Antonio, the town that baptized me with rock & roll.

I sat on my front porch last night under cloudy San Antonio skies. It’s been hellish hot this summer, over a hundred degrees many times, but yesterday afternoon the autumn sky clouded up unexpectedly and dumped rain on us. It left the day humid. The evenings have been surprisingly tolerable, with a balmy wind arriving after the sun sets, filtered from nearby Brackenridge Park, and the sky a blaze of Mexican gold.

It made me wonder, what was the weather like that November of 1936 when Robert Johnson arrived in San Antonio to record?

Song 30

Written in 1936 by Robert Johnson and Shirley Ratisseau and transcribed by Thelma Ratisseau at the request of Robert Johnson.

Fishin’

We’re goin’ fishin’

Way out on the pier

We’re goin’ fishin’, fishin’ fishin’

Gonna fish right here!

Going bait-catching first

‘Ta see what we get

With a swing-net – throw-net

(Say CAST-Net!) (Shirley)

(What’ll we get!?) (Robert)

Jes’ a little old fish (Robert)

Shiny, silver fishie (Shirley)

SPOKEN:

Ah, small fish

SUNG:

Are you blue like me?

Are you blue as can be?

If you need a friend, I will be one (Robert)

If you need another friend, it’s me! (Shirley)

All together. . .we are three!

Shirley, Robert, and the little fishie

SPOKEN (by Robert):

Friends as long as I live

An’ I remember these days

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.