Photo courtesy of Sarah Hadley. SarahHadley.com

Ravaged Beauty

By Megan Mayhew Bergman

Cumberland Island, Wild but Changing

To encounter Georgia’s pristine barrier islands is to step directly into a space where the strange collides with the beautiful. It seems that every lovely thing is tinged with mystery, danger, or complexity: alligators hunt in the unspoiled tea-colored swamps, eastern diamondback rattlers grow eight feet long, and the sandy paths are shaded by ancient live oaks draped in Spanish moss. Seventeen-and-a-half miles long and three miles wide, and accessible only by boat, semitropical Cumberland Island is the southernmost of Georgia’s Sea Islands. The United Nations has designated it a global biosphere, given its biodiversity and criticality to endangered species. At its core is a deposit of Pleistocene sediments; it was divided from the mainland as sea levels rose, and it continues to separate from its neighbor, Little Cumberland Island, for the same reason.

Cumberland’s beaches appear virginal and empty, and, as part of the Atlantic Flyway, are home to dwindling populations of sea birds like plovers and oystercatchers. The occasional poacher still makes a grab for turtle eggs, smuggling the slippery, golf ball–size orbs into coolers. The eggs carry street value as aphrodisiacs and men swallow them whole in back-alley bars, hoping for sexual performance that rivals the notoriously long mating sessions of loggerheads.

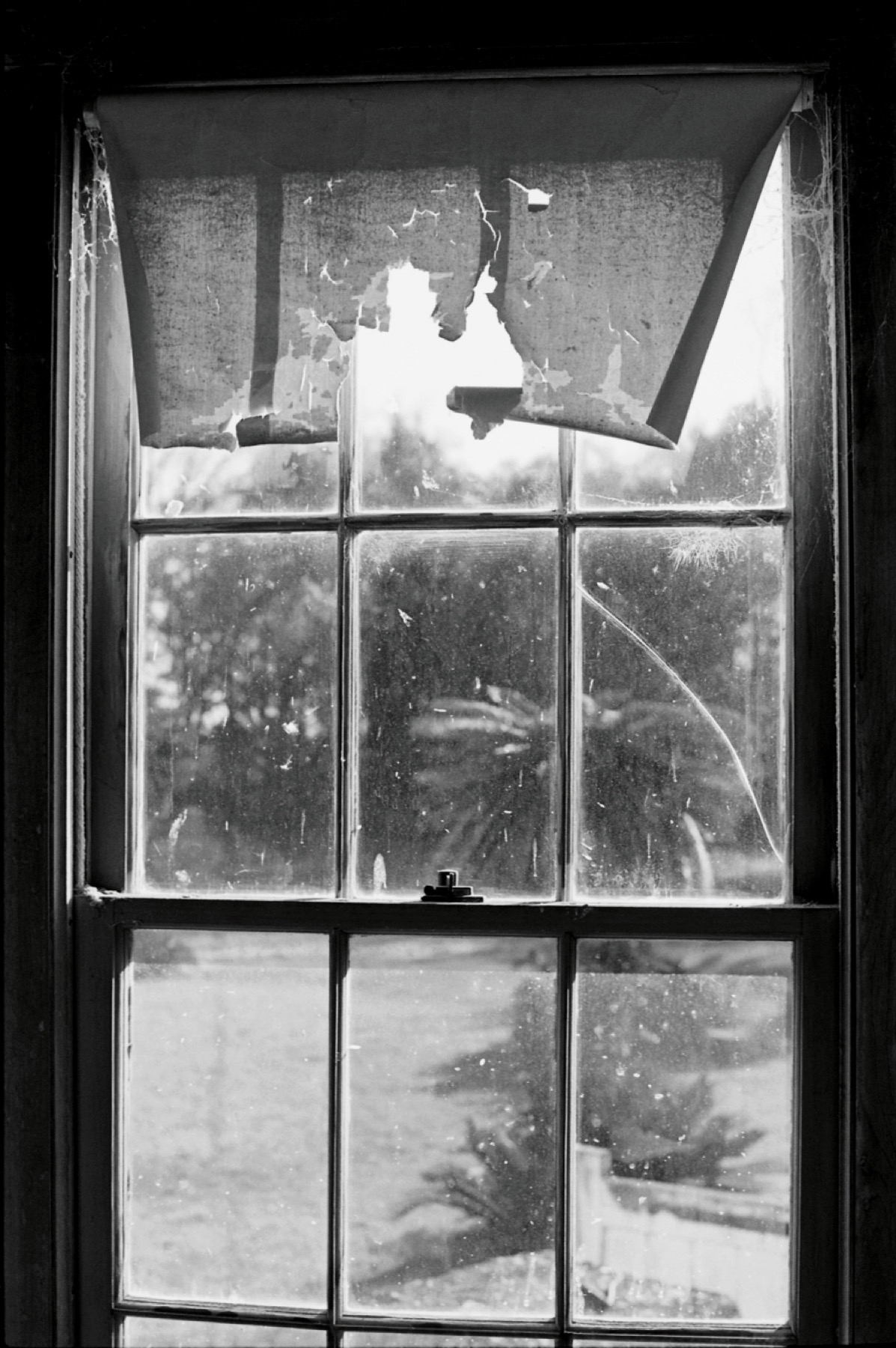

Books and pamphlets about Cumberland Island frequently include the phrase “ravaged by time,” a nod to the ruins of a mansion once known as Dungeness jutting up from a knoll, a jagged silhouette of bricks and timber. As I gathered supplies before catching the ferry to the island on a February morning, I thought of the oft-used line from Marguerite Duras’s novel The Lover, in which one character remarks to another: “I prefer your face as it is now. Ravaged.” I’m drawn to imperfect places, places where nature has regained its edge, vines curling into windows, paths left unmanicured. I struggle with the modern-day presentation of plantations, the wedding-friendly Vaseline lens that too often obscures the harsh realities and human costs of past operations. Given the island’s complex social history, it occurred to me that I might prefer the island ravaged by time, as opposed to its earlier opulence as a plantation and later a vacation home of the Gilded Age.

As we waited for the ferry, my guide Catherine, a conservationist and sea turtle expert, and I listened to a young park ranger’s practiced speech.

“You need to smell any seashell before you put it in your backpack,” he said wryly to the crowd waiting to board. “If it’s not finished dying, you’ll be sorry.”

“I need to remind you,” the ranger continued in his deadpan voice, “the wild animals here are indeed wild, and you should not get close to any horse, bobcat, hog, coyote, alligator, or armadillo you happen to cross.”

“I’ve never seen an armadillo,” I whispered to Catherine.

“Don’t touch one,” she warned. “They occasionally carry leprosy.”

The ferry ride was brisk, but the sun was already coming on warm, and when we disembarked, Catherine and I stopped at a picnic table to cover ourselves in sunscreen. We walked the sandy paths underneath a canopy of moss toward heavy iron gates. I imagined what visitors once saw at this juncture: a fifty-nine-room Queen Anne–style estate, neat lawns, palms, arched window casements, chimneys rising from an endless roofline, and a central tower on the horizon, not unlike a minaret, where Lucy Carnegie (sister-in-law of Andrew) was rumored to have secluded herself during times of emotional distress.

The presentation of the ruined mansion is forthright—simply the foundation of a charred estate and its structural elements: thick brick walls and gaping holes like mouths where windows and doors used to be. Nearby, the wooden siding of the once-grand indoor pool house has splintered, demolished by sea breeze. In 1959, Dungeness was set aflame in a dispute between a poacher and a caretaker.

As we walked past, two thin horses with indifferent eyes grazed the dry grounds. They belong to a band of feral horses, a herd of less than two hundred, likely related to those brought over by the English in the eighteenth century. The horses suffer parasites, poor nutrition, social instability, and sand colic, but they persist, weary and beloved.

There are vestiges of the island’s past life everywhere, layered on top of one another like the sacred shell mounds that formed the foundation of the original Dungeness.

And who made those early mounds, the sacrosanct piles of earth, shell, and sand? When Europeans arrived, the island was home to Timucua Indians. William W. Winn, who penned a history of Cumberland Island in the 1970s, writes that the Timucua were, according to what the French Huguenots reported in the 1560s, “intelligent though frighteningly pagan people who worshipped the sun and the moon, carried out human sacrifices, and allowed their fingernails and toenails to grow to hideous lengths. They were capable of putting on a fierce visage, lacquering themselves with bear grease, tattooing their bodies with macabre designs, and dressing in Spanish moss.” The Timucua overlapped with the era of Spanish missions—a time of trade, conflict, and disease. Between Indian, Spanish, British, and pirate activity, the islands endured a period of instability.

Social reformer James Oglethorpe followed. Oglethorpe aspired to rehome Britain’s “worthy poor” in Georgia, transforming the lower class into artisans and farmers and starting the royal colony of Savannah. He built a hunting lodge on Cumberland as a vacation home, the original Dungeness. In the late 1700s, Revolutionary War hero Nathanael Greene’s wife Catherine, known as Caty, built an enormous tabby mansion. At one point, after Greene’s death, she maintained more than one hundred slaves and eight hundred olive trees. Recollections of Caty, according to Winn, portray her as “mean, immoral” and note that “she drank too much, that she would think nothing of shooting a slave, and worse.” She was buried on the island, near Robert E. Lee’s father, Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, who was rowed ashore from a schooner in 1818 to die on Cumberland. (His body was later relocated to Virginia.)

The Stafford family ran two plantations on Cumberland until the Civil War sent them toward the mainland; Union soldiers then made camp on the island. The Carnegie era began in the 1880s, when Thomas and Lucy fell in love with the ruins, and built the last incarnation of Dungeness. Subsequent homes for their children followed, many of which still stand, including Greyfield, built for Lucy’s daughter Margaret Ricketson. Margaret’s daughter, Lucy Ferguson, converted the home to an inn in 1962, several years before island natives thwarted a move toward development, with an entrepreneur giving up on his project and selling the land to the National Park Foundation.

In her book about the island, Carnegie relative Mary R. Bullard notes the term islomania as used by English poet Lawrence Durrell. “There are people,” he wrote, “who find islands somehow irresistible.” Just before Bullard’s brother Oliver G. Ricketson III sold his land, he wrote a letter to his children, claiming, “My generation of cousins has been profoundly influenced by the island, some for the better and some for the worse.” Cumberland has all the markings of a sacred place: a fraught history peppered with lore, the sort of primeval wilderness one cannot re-create, and a remote and seductive beauty. One does not question how islanders fall in love with the island, but how they will save it—first from development, and then from rising seas.

What we see now, according to longtime resident and seventh-generation Carnegie descendent Gogo Ferguson, is a rewilding of the island, which was once clear-cut for timber and cotton cultivation. In this era at Cumberland, the few full-time inhabitants and visitors are brought into a startling intimacy with nature, which operates in a more unfettered way than on the mainland. There are no televisions at Greyfield; visitors are encouraged to bring books and walk the beach. Gogo tells stories of nursing injured pigs and horses back to life; she also designs jewelry based on the curve of rattlesnake ribs and starfish limbs. Those who live on the island for some time become deeply connected to it, if not utterly changed.

“Being on Cumberland is like a religious experience,” former shrimper Calvin Lang once told author Will Harlan. I know now what he means. To visit is to acknowledge its eerie, moving singularity.

Though the financial forces that shaped Cumberland were driven by men, the conservation efforts that saved it have been matriarchal in nature. It was Gogo’s grandmother, Lucy Ferguson, who took her on long walks, carrying a buck knife and teaching her to notice animal prints, bones bleached by the sun. Gogo came back to Cumberland as a single mother during the late 1980s—a time, she mentions, when the Carnegie trust funds had been exhausted and work was imperative. Lucy helped ward off development, as did Sandy West on nearby Ossabaw Island, which she inherited from her mother and sold for nearly half its value to the state and to Coca-Cola magnate Robert W. Woodruff in 1978.

One cannot discuss women and conservation here without mentioning Carol Ruckdeschel, dubbed “the wildest woman in America” by Will Harlan, in his book Untamed. Carol is portrayed as nearly feral herself—

riding wild horses naked, swimming to the ocean floor on the backs of the sea turtles she loves, eating roadkill, living in a self-constructed hut made of driftwood, wading into alligator dens. She is a self-taught scientist and sea turtle expert, conducting thousands of necropsies and collecting species in her own museum. Carol, in her purist efforts to save turtles and preserve habitat, is often at odds with Carnegie relatives and wealthy island inhabitants about how to keep Cumberland wild and protected.

The last wild places are rare and vulnerable, and accessing them may eventually become a privilege. This privileged access was on heightened display in 1996 when a young John F. Kennedy Jr. and Carolyn Bessette were married in Cumberland’s now-iconic First African Baptist Church, founded in 1893 by former slaves. The infamous wedding was arranged by Gogo, who loyally guarded the couple’s privacy, and also designed their rings. Carol, later interviewed by the New York Times, said she sat outside her horse barn with a “bowl of popcorn and a beer and a milk crate . . . and watched.”

For more than a century these barrier islands have been a refuge for American aristocrats, freed slaves, misfits, conservationists, and endangered species. Hiking on Cumberland, I pondered the incredible specificity of islands, their unique pressures and microclimates, the endangered niches, the narratives, the women shaped by their love of place. When the wildness of these places is damaged by human-wrought climate change—by the development that Padgett Powell writes disparagingly of in his landmark novel

Edisto—then the flora, fauna, and multifarious social history are likely gone forever.

According to Harlan, it is Carol’s belief that “to save people, we must save nature.” It is a belief I share.

My guide Catherine and I decided to head first to the small graveyard, where Caty Greene is buried, and then circle back to the ferry docks via the beach.

“What are people here going to do about rising seas?” I asked as we meandered for hours, admiring the glint of the sun on the clean water.

We began speaking passionately about the challenge of saving the islands, of navigating environmental conservation in the South. So passionately, in fact, that we became lost in the dunes and low-lying scrub, missing our trail and ending up on a horse path, collecting painful sand spurs in our shoes while we searched for our tracks among hoof prints. We consulted the GPS on our phones only to be assured that we were on “Coleman Avenue”—but not many humans, and certainly no cars, had traveled this road in recent years.

Finally, we rerouted ourselves, crested the dune, and walked the stretch of the uncombed beach into the late afternoon.

“I’ve always loved crepuscular light,” Catherine said. We had our shoes off, toes in the sand, watching seabirds on the brink of extinction fishing in the low tide. The vision of Cumberland Island bathed in twilight struck me as metaphorical.

As we walked toward the ferry, we picked up a soggy Doritos bag—a rare and vibrant object on the pale beach—and two sand dollars. I took one for my daughters. This island could become uninhabitable in their lifetimes. All the coastal towns I loved as a child—places like Beaufort, Charleston, and Savannah—may be swept away by rising, polluted, anoxic seas.

I felt myself falling in love with a place that is poised to change dramatically in the coming century, and I battled a familiar urge to suspend time so that I could return again and again to such reliable, natural magnificence and share it with my daughters. I understood why, for generations, people had become passionate and possessive about the island.

On the ferry ride home, Catherine confessed to me that she rarely uses the terms “global warming” or “climate change” in communications, instead opting for the less political “rising sea levels” and “changing coastline.” While some members of the community accept the scientific realities—like many of the state’s shrimpers who have seen the results firsthand—there are still politicians and donors who believe global warming is a liberal ruse. This raises the question, how can the country’s southern coast, so rich in resources, wildlife, and social history, protect itself if the terms in which it must be discussed are politically polarizing and unpopular?

While I was in Georgia, NASA scientists reported that February had exceeded a century of global temperature records by a “stunning” margin. Well past a tipping point, we must begin to accept that islands like Cumberland will be ravaged not by time, but by rising seas and by scalding hot summers, which change the sex of turtles in their eggs, alter the coastline, discourage summer visitors, bring in alien species, and turn out the indigenous.

When I got back to my hotel—a sweet, moss-draped villa on Saint Simons with white lights and live music, and men at the bar making impolite jokes about President Obama—I unpacked my bag only to be greeted by the sulphuric, rotting odor of the sand dollar.

Perhaps, despite my best efforts to confirm its death, it was not finished dying. One must not write off the living.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.