The Battle of and for the Black Face Boy

By Nikky Finney

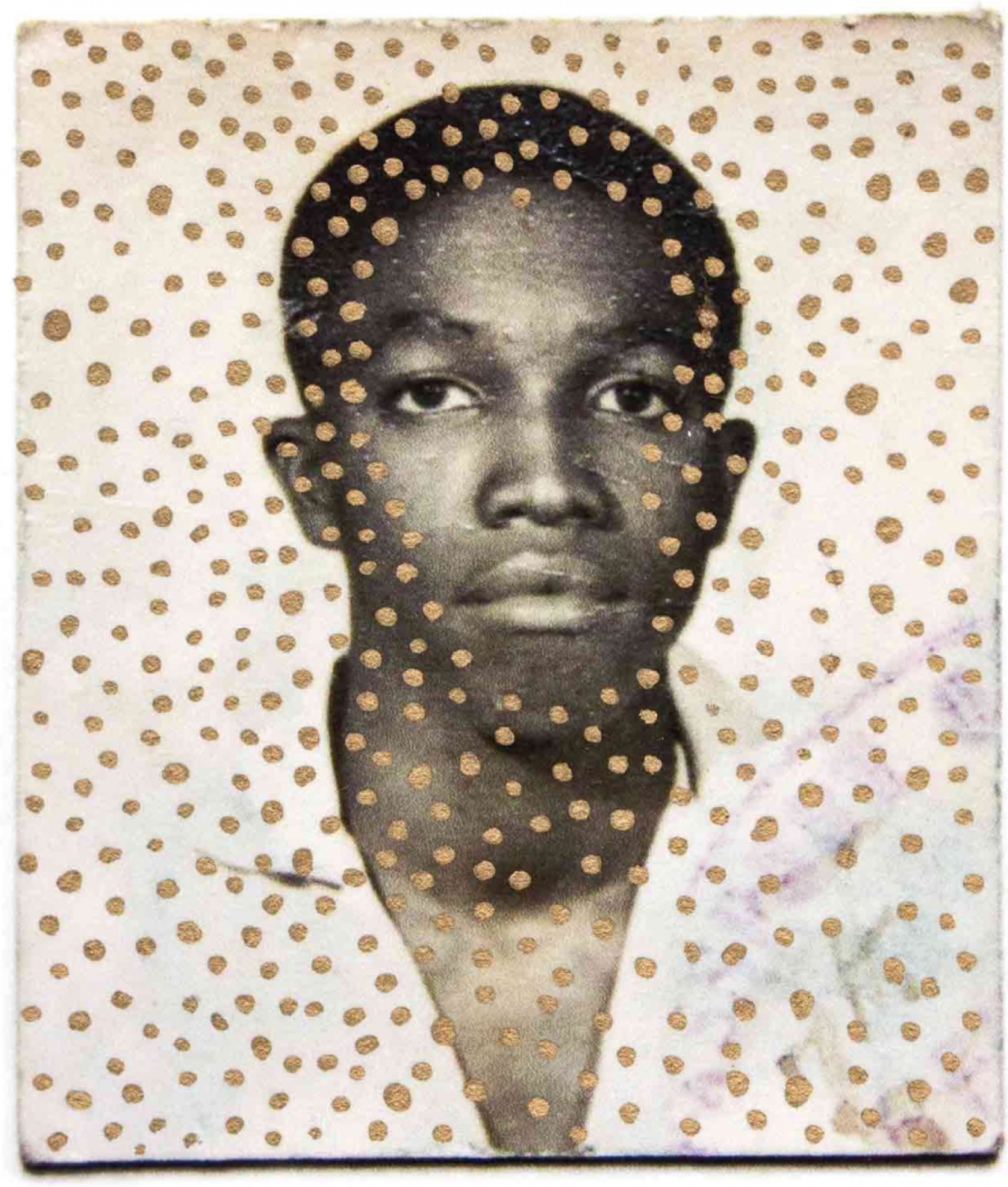

“Untitled,” from the series Passports, by Keisha Scarville

“I imagined a radical libretto made of Civil War history, Black history, and modern American headlines.”

— From Finney’s introduction to “The Battle of and for the Black Face Boy.”

Black boys needed to turn swamp forest into white gold!

In 1851 he is stopped and frisked,

packed inside the ice of iron,

in the hull of the Jesus, on his back

eighteen hours a day, one hundred

and ninety-two days, he has three

square feet of space and ten vertical

inches of air, the cat-o-nine tails

whips away, the jaws of the speculum

oris feed him horse pea mush,

startlingly, strike with wonder,

he is alive, the devil is beaten out

of his father, sharks nose the water

for his boat, one hundred times as

many black face boys thrown overboard

will eventually make the passage,

the new world’s cardinal child is robust,

disposable, appraised and weighed,

in great supply,

Open wide black face boy, open wide, our brave new world will make great use of you!

I twist to my right looking for my father who is no longer three rows over. Another boy my height and weight chained wrist to ankle has split open the back of his head by beating it against the wooden planks beneath us. His eyes have pitched and quaked and rolled back now. Once on shore my name is Lawless and I am barely breathing. They stand me up in a vat of palm oil. My black face is the first microchip. It will be rubbed and watched for more than two hundred years. As long as I wear this black face they can find me anywhere. I have been hauled here by them for them. It is illegal for me to be outside without them. It is against the law for me to wear clothes with a pocket. A pocket is for privacy and mine was stripped and thrown behind me in the salt waves. Now that we are one big family a pass or a civil war will be required to zigzag cotton into wool. On slave row I am marched to my strip of red dirt floor. I am given my three square feet of space and my ten vertical inches of air. In an almost dead boy’s dream curl I drink down the free hips of black women patted and swirled in African coconut dust. Daylight comes. Plantation people walk by stiffly in long ruffled skirts and top hats that hide the sweet sway of the body. I grow into a man and learn they call this manners and grace.

The women plundered with him

are opened and entered like fish

mouths, his sisters are swept and

blown into the air like dandelion,

pussy willows, weeping willows,

black-eyed Susan willows, each

will grow furiously, dangerously,

across the mantle of the new land,

peony girls will pop, top heavy

hydrangea women, drenched in

indigo and poppy, fluttering inside

the dark-eyed suckle of sugar

and cane, their motion picture

hips throwing seed,

Black boy rubbed back alive, rubbed up for luck, rubbed on for sale and battle!

It is the age of cotton futures,

iron slave collars and copper

yoke bracelets, the foreheads of

black face boys are tattooed with

the bone white of the master’s

initials, BMI, he hears them talking

through their sweet tea liquor

vote no to the Union and yes

to keeping slaves in their fields

(in their beds), Generals Lee,

Beauregard, Stonewall Jackson,

John Hunt Morgan, the cotton

Confederacy lifts into the orange

air of the Republic, pointing

a rusty 1861 Kill Every Nigger

Tillman gubernatorial submarine,

Slavery now! Slavery tomorrow! Slavery forever! Slavery on the moon!

Four score and forever I am told to never look him in his eye. A clamp is kept on my mouth. I learn to count on the rest of my staring body for everything that I need to live. I forget their eye- rules sometimes when he divides us up and sends us away from each other like biddies. I draw my chin up just enough to see what kind of creature is standing before me. I have to look at him to make sure I never forget. After I look he beats me at the whipping tree for staring. I raise my chin and stare again at his backside as he walks away. What kind of creature could pull a mother from the fingers of her child or a husband from the elbows of his wife? Into the back of his neck and shoulders I send my eyes to remind him there will be no forgetting what he has done. Before he turns and catches me staring again I stagger back to the wagon to strap on the mule’s harness that is my coat and move on down the row. I need none of his pockets for the keeping of these plantation black and whites.

The age of enlightenment is over,

here comes the time of civil war

pell-mell, the battle of Ft. Sumter,

the delicate dance of the cakewalk,

jump and jute, collide, mid-air,

Charleston’s cannon balls, African

banjos, English lutes break the air

in one accord, the age of cotton and

peach preserve, the birth of war

paint and dead arm photography

take the floor, pale humans curtsy,

bow, flash, grin, then shoot each

other in the face, the music of the

age is classical, arguing who is and

is not free, the plentiful, unsurpassed,

forever calculating, black face boy,

is now and forever,

dragged center stage,

Henceforth and forever more the Republic can never afford to be disinterested in black face boys!

A joint announcement is made,

black face on black face boys

from this day forward shall be

the Republic’s prototype, usufruct,

his instincts and his chemistry,

will be used to sell tobacco,

hot dogs, box seats, toothpaste,

all in his persuasive name, used

to calculate how to boldly break

the union, sweetly save the union,

ink amendments, acquire but

never allow the Siamese twins

Freedom & Equality to marry,

ink declarations and squander

proclamations, South to North,

everyone agrees off record that

he will never be much to crow

about, but they will never take

their eyes off him, never will he

be forever free, and everywhere he

tries to move the music of his

soft tapping feet will sound out

train trestle, iron bells, smokestack,

gold coins, siren bullets, panic,

what they can sell of him will be

well marked, but never will any

black face boy parts be labeled

leading or man, black skin,

the Republic’s first microchip

is strategically placed,

is working very well,

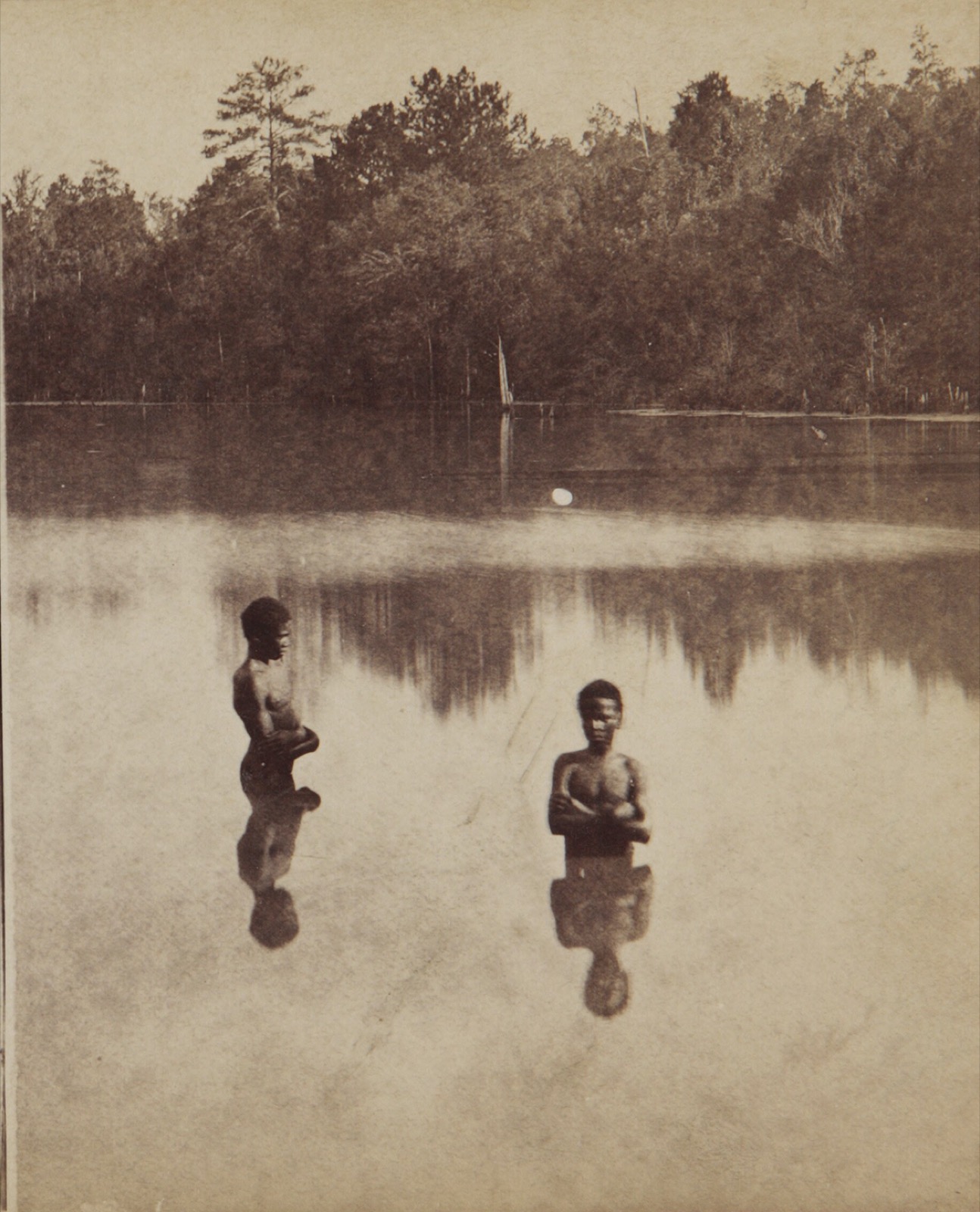

“Jamey’s Horse,” Maringouin, Louisiana (1997), by Jack Spencer

“Jamey’s Horse,” Maringouin, Louisiana (1997), by Jack Spencer

Black face boy the world is changing but we still have a great and growing use for you!

My black skin is the kind that won’t wash off on or off their minstrel stage of war. I will stay black. Will keep myself alive. Will move upstream with the living. Will will my black body into our great fight for freedom. This Lawless son knows that to fight is to belong. I belong. To my first life. To this nowadays life. To the next life coming fast. I will keep imagining a future with a pocket and without a pass. I will keep moving this black boy body. In my night sleep my feet push on up the road and the dirt floor hears me. Some throats are cut every night. Some songs play on every morning.

Stripped of culture, hulled of

history, shucked of language,

religion, the black face boy

begins to make himself all

over again, from okra seeds

dry tucked beneath his Atlantic

Ocean tongue, from liars’ tongues,

from black and blue memory,

he takes flour from the cotton

boll, milk from cow teats, odd

and end iron from the hull of

the Jesus, eggs and gristle from

beneath warm wet feathers in

the coop (necessary for flight),

the wishbone of a frying chicken

is pushed way down inside his

woolly hair for height, luck, sass,

a mountain climbing attitude,

there has never been one who

had to make himself all over,

from okra and rice, for this he

should be called Sweet Son of

the New World, Sweet Evening

Prancing Star Gazelle, Mr. Boy

Liberty, Sweet Delicious Titanic

Man-To-Be, Son of Mr. Swagger

& Mr. Dash, the Republic’s silent

cinematic heartthrob,

Step forward Nigger! Save your country! The Recruitment poster rings out!

The war blooms, fragrant rotten

Technicolor collision, out-a-sight

black face boys are renamed Contraband

and the Great Available, the tall

bearded statesman from Kentucky

lines them up on land and sea, but

every white face North and South

fears replacing the hoe in his black

hand with an even blacker musket,

Ball’s Bluff, the battles of Whereas

and Heretofore are coming fast,

the age of iron peeled off his black

neck and pushed into a black barrel

is here, the black face boy will step

out and fight his way to freedom

but he wonders if history will

ever carte-de-visite the many

black boy ways he’s

had to move,

General Lee paints graffiti on a recruitment poster when no one is looking. Just underneath a black face he

writes, whispering as he scrawls, “You are now and forever our great disposable!”

The patent pending president

invents a hoisting machine,

fascinated with gadgetry, incendiary

weapons, he has a penchant for

freedom and metaphor, ironclad

warships, and aerial reconnaissance,

he fights with breech loading

cannons, placing his black face

boys squarely on the flaming

checkerboard of the Republic,

hoisting them up and over,

and in, and there, and down,

wherever, however, needed,

Repeat after me: We are engaged in a great Civil War. Say it again! Again!

After Big Bethel and Wilmington,

Hoke’s Run, Bull’s Run, Camp

Wildcat, the hidden horrors of

Andersonville, the massacre at

Ft. Pillow, 2 x 3, six hundred

hearts beneath six hundred sets

of surrendering black arms, high

eye in the air, shot down, the battle

of and for the black face boy

moves into the heat and heart

of the every day war, the feuding

brothers believe they are fighting

for honor, love of and for their

different ways of life, suffering

and pride turn rivers and streams

ruby white & blue, back and forth,

they win, they lose, they blame

each other, whole families burn

whole families down, four years

of muck and misery,

The black face boy is why we are here. He is the cake of all our trouble!

June 20 1864 Private William Johnson who walked away from camp without a pass is escorted back to his own private tree. On a high up hill in plain sight of the witnessing Confederate line the Union stops the war to hang him by his black face neck. Willie Johnson is charged with what I Lawless will be charged with one hundred and fifty years next. It is the black face boy’s charge. Rape + Walking Away. It is a brother’s fight we have been pulled inside the heart of. A point must be made is what the brothers say around their fire pits after Willie swings high in the air above them. Before they cut him down they say liquor loud so that every black face boy yet unborn including me can hear Just because a man thinks he is a man he can not walk away regular—here and there—like other men.

On Navy ships a black face boy

is called a Hand, the first he hears

of this his fingers touch the tar

of his own cheeks there in the

dark sea of night, a full blueberry

moon bent over his set shoulders,

Denmark Vesey stands starboard

holding David Walker’s Appeal,

out on the open water 18,000

black face boys and 11 black face

girls sign up to sail, to fight in

freedom’s fight, once on deck

they boldly learn how to walk

without a pass, their pants are

finally made of deep pocket wool,

they volunteer to step the length

of the cutter all night with their

shoulders pulled back free, new

free black walking human flags,

flags in a brand new free black

wind, port to port they close their

eyes, feel their bodies push away

from chains and cotton to a new

horizon no longer on pause, alive,

reel-to-reel—

Papa Quincy is always there to keep me moving. The flashing storied images of him walking the wet salty planks of a ship in his navy pea coat. His flat cap with matching red flared scarf stained heavy with the ivory of guts and dried whale blood. Not all of us came by chains. Four hundred counted here and there with whale tattoos from another day and time. A time when black face boys were given hunting spears without fear of whose flesh the tip would tear. His whale soaked face making him a maritime man. Long before any uncivil war pushed to name anyone who looked like him Contraband. He fought the humpback and the blue for their sweet burning oil not Confederates for their blackened cotton. The story that traveled to me told that he knew John Robert Bond of Liverpool who enlisted to “help free the slaves.” So many black boys wearing the knot of the Navy in order to slip the knot of the noose. Never shackled on his back for eighteen hours. Never chained in the ice of iron for one hundred and ninety-two days. Theseones sailed and reached back for black faces just like their own. On the high seas there were black literate sailors reaching for Philadelphia newsprint and any word of their brothers chained away in the South. I see Quincy Lawless whenever I move through any minute of my day. I stride to his side without thinking and stare into his history. Whispering as he leans over the ship’s railing to read to the black face men that I will never know. He uses his long black pointing finger as he holds tightly to all of us with every word O’ yes O’ yes one day dear brothers of the bottom land you too will belong.

Niggers in wool riding on ships! Next thing you know they’ll want God’s sweet acres and Bess his mule!

It is the age of the final count,

under the silk of Alabama fields,

beside the charcoal of Tennessee

streams, in Maryland pushback

sand, inside the Potomac, the long

brown thigh of the Mississippi,

750,000 bodies of brothers and

ex-slaves, side by side, five hundred

thousand more hacked by war,

now bandaged and wandering

hospitals and field stations, there,

nineteen black boy legs cut away

atop a pile of all white arms, here,

one teal blue eye motionless in a

honey jar, staring across the room

at one black boy, eyeless, but alive,

on the floor,

squat and bleating,

We still need you black face boy! In wartime! In Peacetime! You are truly boy of boys!

It is the age of electricity,

Black Mary moves quietly out on

the dust bowl prairie, the kneeling

Confederate flag is really a rusty

1865 Tillman submarine sinking

into the deep, Kill Every Nigger is

now disappearing beneath the

bubbly pearl of waves, General Lee

takes up his pen at Appomattox

to finally sign the old etiquette

of the Old South away, promising

to, in the future, give black face

boys more than three square feet

of space and ten vertical inches

of air, the new promise fools the

Republic into believing all involved

have left the darkness behind,

all have not, but if you throw your

eyes far enough, word on the western

prairie promises, Black Mary rides

roughshod on wooden pulsar wheels,

she and her black woman stagecoach

delivering mail to the outer banks

Republic and the tumbleweed nuns,

a shotgun squared between her legs,

a tobacco pipe is barbed wired

between her lips,

Soon it will be the age of moving

pictures and television, and after

that the battle of the newest steam

engineered trains arriving late at the

station, COLORED & WHITE

will peer atop every southern water

fountain, black face boys and girls

will march and sing to the drumming

of water hoses while levitating

shoeless across the Edmund Pettus

concrete lift, desiring immediate

adoption of the Republic’s illegitimate

moon-faced cousins,

FREEDOM & EQUALITY— Untitled photograph (ca. 1875), by J.N. Wilson. From the Randolph Linsly Simpson African-American collection at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library

Untitled photograph (ca. 1875), by J.N. Wilson. From the Randolph Linsly Simpson African-American collection at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library

At 109 Uncle Julius Lawless called it the age of black chicken skin.

Everybody listening and remembering on the porch was nervous.

They had a feeling trouble in double doses was on its way. First a

black face boy from Atlanta took his last walk on his last balcony

in Memphis. Then two more black face boys stepped up to the

winner’s block to raise their black-gloved fists over Mexico City.

Grandma says the age of plastic has cometh and ice is now

melting on continents where ice has never melted before. Even I

know the waters of the world are beginning to churn with our

greed and ignorance. Dynamite and exclusion have become the

national rage. Four little girls from Bombingham have been

watching over us in their flaming Sunday school dresses for fifty

years. The black face boys I know know little has changed even

with all the changes. The black face boys I know know their great

uncles walked from West Virginia to Washington with their

inventions in their arms and on their backs. Our music and our

perfect calculations pushing the mean world ahead.

You are never to be trusted black face boy. You are guilty of things that haven’t even happened yet!

It is the age of liars, co-liars, fear,

gun shows dot the land like golden

bales of amber wheat, the Republic

is deeply worried about the gates

of the old city, it used to be clear

who could walk in without a pass

and who could not, who could stay

and work with or without a pocket

or a pass and who could not,

who could vote and who could be

Mr. President, it used to be easy

to tell who was who (in their beds),

black face boys know who they are,

they are the sons of men, just like

other sons know, they are boys who

want what other boys want, the wild

freedom to invent, to freely be them-

selves, the freedom to not have one

thing in their pocket needed to get

safely home, the freedom to have

nothing to prove, to play basketball

freely, to not play dead every night

while freely walking home late from

the free hoop park, the freedom

to never hide their heart, their hands,

their heroes, or their wicked walking

on their high horse haunches,

that free bow legged walk that makes

black boy country waves, the black

boy freedom to weave, swagger,

swerve and not be stopped, not be

tasered down (blessed be what the

cell phone sees), running-for-their-life

black boys, still given three square feet

of space and ten inches of

black boy air,

We will never give you room. The only war ever fought here at home was about making room for you. Now! You are it!

It is the 8th age of extinction,

scientists are bringing the woolly

mammoth back, prison cities

rise on the Republic’s new map,

newly coined black face boys

spend their days locked down,

side by side, on their Atlantic

Ocean backs, eighteen hours

on federal concrete, human forks

and spoons, living out their time

in the new ice of new iron,

black boys with back pockets

and front, it is the age of not

enough black face boy poets,

tea salesmen and fresco painters,

the age of electric cars and electric

black face boys, the age of shooting

black face boys in their black electric

faces and backs, the Republic’s

new red velvet big tent show,

the age of white boys growing up

on the treble and bass of black

boy songs, while black boys now

and in the future, never get to grow

up, black boys who are gunned

down by the fathers of those,

buying and listening to their music,

shot again as they knock on the

door of the Republic needing help

with a dead battery, Honey, he says

all he needs

is a jump,

Jump black face boy! Jump! Nobody jumps as high as a black face boy!

Through the peephole the Republic peeps at me. Junior Lawless

of the dark woolly-haired crew. Lawless Jr. of the woolly dark-eyed

caravan. Whenever they look at me they see Civil War. Rape. The

great historical dismissive black boy walk away. When they shoot

me and leave me in the street for four hours facedown on the hot

summer pavement while my mother screams on the porch they

see sugar plantations melting in the distance. They see cotton

fields handed over to boll weevils on a British silver platter. They

see money on fire. They see their great granddaddy’s wooden arm

and bloodshot eyes in a ditch. They see their great grandmothers

facedown in the red mud cotton rose fabric hiked up to her hip.

They see me coming and want to go Civil War on me. When I

walk in they see a musket loaded between my legs ready to shoot.

They see Sherman walking on baby blue water down to the sea.

They see my black body and they see 10000 bloody trenches in

tow filled with white boy body parts. My nappy loud hair is the

51000 of Gettysburg still rotting in the field. My double sub-

woofers and tweeters playing The Notorious B.I.G. at 50 decibels

is the 23000 shot in twelve hours at Antietam. They see me in

black shiny neon skin. They see me and trouble tickertapes like

sea smoke through their annual Confederate reenactments. All

because of me. Me and my little need to be free.

It is the age of wily Wall Street,

the Republic strikes up the money

making band needing to sell nothing

for something, that is what profit is,

so the deep pockets of the Republic

think future and focus on music

and muscle, once again the Republic

fixes its blue eyes on the sons of

black face boys, those who first

aroused the first big money micro-

chip, a whole country founded on

their rich black skin, immediately

they separate those who can run,

pass, and jump and perhaps even

hold a high velvet note, from those

whose black faces are not smooth

enough and must stick to selling

fake Civil War memorabilia

on the corner,

Look away now boy, look away, remember, don’t look me in the eye, look away now boy, look away!

It is the age of surrender,

black face boys, still in great

supply are made into the new

Republic’s old moneymaker,

“Heads” he stays and entertains,

“Tails” he goes to jail, the black

face boys on the corner with

trinkets and souvenirs to sell,

first resist, then remember,

then get busy reinventing,

like their fathers, they can only

use their minds and what is left

on their backsides as tool and

dye, they loosen and lower their

pants beyond the Republic’s

legal hip line, cinching the sail

cloth of their whaling fathers

in their left hand, while pushing

their black boy freestanding

legs out in front to the right,

they know not to run unless

a metronome game clock ticks

in tandem with every leap,

but their legs can’t help it,

they move in black face boy

stride and time,

Like a pod of black face whales

moving through an oil slick,

they move in silent refusal of

their generation’s allotment of

their three square feet of space,

their ten vertical inches of air,

this up-to-date, still disposable,

abreast-of-the-times, foremost,

black face boy, this cardinal son,

is not seduced by cannon fire,

suffering or death, he knows

what he knows and he knows

what the Republic will never

admit, he knows what and who

the cherished beloved is, he was

there when it was built, he built

it, when the only thing there

was dirt, to dig, to move, to sleep

on, when the only thing there was

sun up and sun down, was dreams

to chase out of his head, a cotton

tom-tom pounding, the sound

of slaves ringing up on cold cash

registers before sinking to the

bottom of the Atlantic, was whips,

was an iron bit that reached from

his mouth to his eyelashes,

was his chest pushed into a tree

that a whip had long long

ago stripped clean,

He is here & here & now,

there & there & now, and

he has seen and knows what

the Republic betroths to each

and every beloved boy, one orb,

one tassel, the right to move

freely, to get the hell up and go,

the trendsetting, newly minted,

streamlined, black face boy,

first ordained by their civil war,

empties his pockets, cinches up

his long illegal legs,

and again, like his father,

shrewdly,

starts to move,

the black face boy has reinvented walking.

“Black Boy with Flag,” from the Robert L. Scott Collection of 19th and 20th Century African American Vernacular Photography

“Black Boy with Flag,” from the Robert L. Scott Collection of 19th and 20th Century African American Vernacular PhotographyEnjoy this poem? Subscribe to the Oxford American.