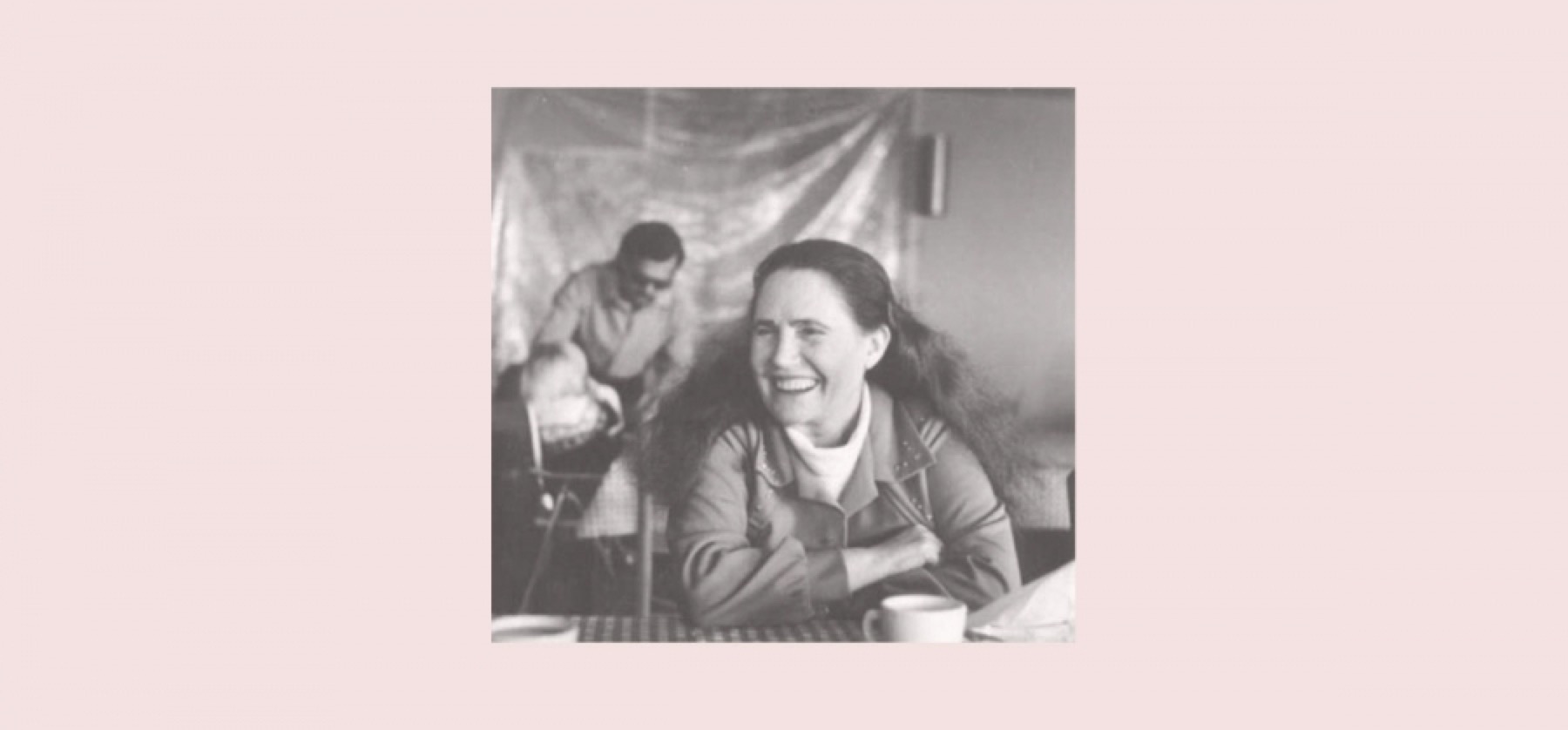

Sarah Ogan Gunning. Source: Candie Carawan

“I'm Going to Organize, Baby Mine“

By Elyssa East

2017 Southern Music Issue CD featuring Kentucky

Track 11 – “I’m Going to Organize, Baby Mine” by Sarah Ogan Gunning

In the Eastern Kentucky coalfields, unionism—or its lack—was a creed people held and defended as fiercely as those of the region’s charismatic religions. And the music Sarah Ogan Gunning and her siblings produced between the 1930s and 1960s was as steeped in unionism and communism as it was in the traditional songs, ballads, and hymns of Appalachia. The siblings grew up on the strike lines with their coal miner father, union member Oliver Garland, who was also a preacher. Songs like Gunning’s “I’m Going to Organize, Baby Mine” (based upon a peppy tune often known as “Banjo Girl”) helped to galvanize the miners and their wives, Gunning among them, who organized the strikes.

These are miners’ chilluns and wives

I’m compelled to save their lives,

So I’m goin’ to organize, baby mine!

It’s unclear when exactly Gunning, born in 1910, penned these lines. She didn’t start writing her own material until 1936, after Leadbelly chauffeured New York University folklorist Mary Elizabeth Barnicle up Eastern Kentucky’s dark, twisting mountain roads. They had come to move Gunning and her three remaining children to New York City, where medical care was better and their economic conditions would be moderately improved. After a while, Gunning’s ailing coal miner husband followed. Two years later, Gunning’s husband was dead from tuberculosis, from which she also suffered. Less than a year after this heartbreak, she buried her son, who was just shy of three. He was her second baby to die.

Barnicle had made her way to Gunning via Gunning’s older half sister, the firebrand radical singer Aunt Molly Jackson, whom Theodore Dreiser brought to fame in 1931 when his committee of fellow left-leaning novelists and journalists traveled to Harlan County—a.k.a. “Bloody Harlan.” Dreiser held hearings and reported back to the national press on the violence and hardship during the area’s coal wars. He was as impressed by Jackson’s and her half brother Jim Garland’s radicalism as he was by their singing. Communist sympathizers brought Jackson to New York. Garland followed in 1935. Remarkably, no one had told Barnicle that Gunning could sing, too.

Oh, but she sure could sing. Just ask Woody Guthrie, who described her voice as “dry as my own, thin, high, and in her nose, with the old outdoors and down the mountain sound to it.” In addition to singing solo, Gunning performed with the Kentucky Mountain Singers, her brother Jim’s group. The three siblings were right in the center of the first urban folk movement, along with Leadbelly, Guthrie, Burl Ives, and Pete Seeger.

In contrast to the music of her siblings, there’s a tenderness and vulnerability to Gunning’s songs, which are drawn from her life in the way of gospel testimonies. As Guthrie, who recorded his own version of “I’m Going to Organize,” put it, “Sarah’s homemade songs and speeches, made up from actual experience, are deadlier and stronger than rifle bullets, and have cut a wider swath than a machine gun could.”

That influence extended to the 1960s, when Gunning was rediscovered after a twenty-year hiatus from performing. By then, she was living in a basement hovel in Detroit with her second husband. Tuberculosis had ravaged one of her lungs, forcing her to have it removed. Nonetheless, by 1964 she was performing as a solo act at the Newport Folk Festival, introducing a new generation to her signature style and to the stories of those babes of hers and the Eastern Kentucky coal miners whose lives were tragically cut short.

Return to the Kentucky Music Issue liner notes.

Order the 19th Southern Music Issue & CD featuring Kentucky.