THE GREAT INVISIBLE

By Kira Akerman

“We live in Capitalism,” Ursula K. Le Guin said as she received a medal for her “distinguished contribution to American letters” at the National Book Award ceremony in November. In her speech, she called on writers to see alternatives to how we live now—writers who can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies, to other ways of being. We need filmmakers, too, who make our own hubris, our destructiveness, and our relentless pursuits visible, and put choice in our hands: will we turn away, or look at who we are, as a culture?

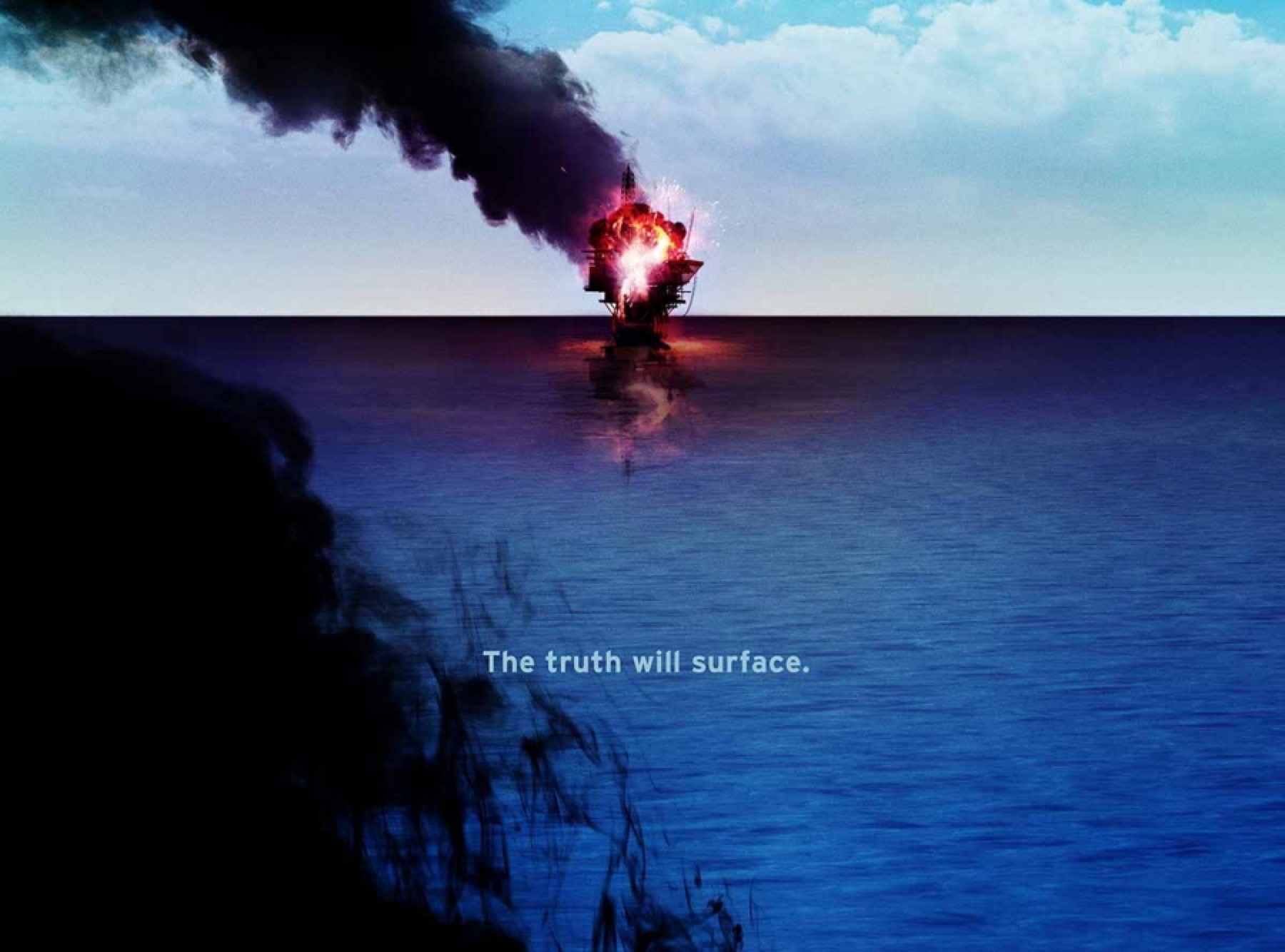

Margaret Brown’s ninety-two-minute documentary, The Great Invisible, chronicles the Deepwater oil spill, the worst spill in U.S. history. On April 20, 2010, oil plumed from the offshore wellhead, and spread on the ocean’s surface. Some oil suspended in the water, and some sunk to the seafloor. The catastrophe began with a rig explosion that killed eleven workers, and then discharged millions of barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Congress still has yet to pass any safety legislation on the petroleum industry, and there are now more rigs in the Gulf of Mexico than before the disaster. Brown’s film The Great Invisible is a reminder of our limited ability to harness nature for our needs.

The oil industry is indeed “the great invisible,” appearing as the gas that we pump into our cars without ever actually seeing it, without ever thinking about our connection to the vast factory of pipelines under the Gulf of Mexico. But “the great invisible” is much more than the oil and the greed and destruction it incurs. Its metaphor extends to everything we don’t want to know too much about, in favor of our comforts.

How did you begin The Great Invisible?

At first, I was mainly concerned with the question of what would happen in the area of the Gulf where I grew up. After the spill, my dad would give me a daily update on his shrimp nets, if they were bigger or smaller than normal. And he sent me pictures of our house in Alabama surrounded by “boom”—these orange inner tube–like things, which supposedly prevent oil from reaching the beach. But it was totally cosmetic. The tubes were a dispersant. They sunk oil, but didn’t get rid of it. It looked like an invasion. Like a war. People were freaked out, and there was a great fear that a way of life would be lost—life on the water.

About a year and a half of this, I started seeing the bigger picture. It suddenly felt personal. I started to ask, ‘How am I connected?’ and ‘What is really going on?’

How do you think oil speaks to our culture at large?

Oil is part of the culture of convenience, and that’s reflected in the way we think about it. We just fill up our cars without thinking of the guy on rig. Our mind draws a blank, and we have crazy incentives to use more fuel. Lisa Margonelli writes about how gas pumps are designed to like ATMS. That’s specifically to diffuse our anger about putting this highly volatile substance in our cars, because supposedly we feel good about our ATMs. It’s a game of smoke and mirrors; we are doing it to ourselves, but the facts are deliberately being hidden, as well.

Do you foresee any change in oil policy?

It’s not going to happen in Washington. Too much money is involved, and the Republicans have pushed back on any kind of regulatory changes that have been proposed. It’s quite sad to me because safety shouldn’t be a partisan issue. I think there’s the beginning of change with the People’s Climate March. It’s got to be a grassroots movement to convince our elected officials that we need a change.

Did anyone ever apologize to the survivors of the BP oil spill?

It’s really strange that no one from these companies ever said “I’m sorry” to the survivors from the explosion that I interviewed. No one said that really simple stuff, which struck me. Saying something makes a huge difference to people.

Can you describe how you see the relationship between the South and the North, regarding the BP spill?

When I first started making this movie, people in the North were able to easily say, “Go get BP!” (while at once demanding their heaters run). They didn’t understand the intense pride Southerners have in producing oil. It pays for college educations. How could that be negative? A lot of people in the South work in fishing part of year and on rigs part of the year. In Louisiana, there’s a Louisiana Shrimp & Petroleum festival. It’s symbol is a shrimp around an oil rig. No one’s thinking, “Oh, the oil is hurting the shrimp.” But now, I think people in South are disenchanted with the oil industry in the way they never were before the spill.

Did you try to go offshore during filming?

I did try to go offshore, but in the end wasn’t able to get on a rig—no company would let me. It’s not exactly a tourist destination; it’s a dangerous place, and most importantly, I’m sure they didn’t want a filmmaker out there.

However, a diver I interviewed who worked for Shell thought it was very important for me to understand the industry’s culture, and he paid for me to go through the training that you have to undergo to go offshore. There’s a written test, and then there’s a helicopter crash simulator that dunks you underwater, turns you upside down, and disorients you and you have to take off your seatbelt, punch out a window with your arm, and swim out the window. It’s very disorienting but kind of fun, like an amusement park ride. I don’t think there’s any way possible that this could actually prepare you for a helicopter crash, but I’m not sure what would. As for the written test, it reminded me of multiple-choice quizzes in my public high school. Everyone was cheating, and the teacher knew it. It was a joke—basically a hoop to jump through so that the company can say “you were trained.” The training didn’t teach you how to think, or how to solve a problem.

What insights did you gain from the training?

From the folks in my movie and others I’ve interviewed that work offshore, I feel that the main problem there is the culture. There’s a “git er done” mentality that is effective most of the time, but it doesn’t allow people to question authority because they are terrified of losing their jobs. It’s very militaristic in that way, but the difference being that their underlying motive is to save time and money. There are these are highly paid workers, most of whom are not educated and who therefore don’t have other options. So they’re going to do just about anything to hang on to this job. That is the system we are up against when we are talking about making changes in offshore culture.

Remarkably, The Great Invisible doesn’t point any fingers. Everyone is implicated by the oil factory under the Gulf of Mexico. Did you come to any personal conclusions that weren’t spelled out in the film?

No. I feel like the film says what I want to say and much more eloquently than I could put it into words actually. But I do think the film points a finger—it points it straight at us, the consumer, to get educated beyond what the industry wants us to believe, and to see how deeply and directly we are connected to the pipelines that are coursing through the Gulf—the 3500 platforms that are out there connected to as many as twenty wells each. That’s a lot of holes in the ocean floor that we are punching out to feed our need for cheap petroleum. I’m not saying I don’t find BP’s conduct egregious, disturbing, and unacceptable, but I think we need to look beyond that to a systemic reboot and a rethink of how we’re going to power this planet in the upcoming years.