Notes From A Balletomane

The dancers keep falling.

In other competitions, these gravitational mishaps are called crashes or stumbles, but here are the world’s ballet elite: even when they fall, they are graceful. Contestants from South Korea, Mexico, Brazil, Japan, Russia, and the United States appear before us and, as if cursed en masse, crumple on the landing of a grande jeté or stumble emerging from a bombastic blur of pirouettes. Tonight, something outside of their reckoning keeps happening and it is disconcerting, spooky even, to watch. I am in the front row—close enough to track errant sequins, loosened from tutus, drifting to the floor. And so on this final night of the competition, I feel somehow culpable, involved in what I imagine will be moments—split-seconds—that these creatures of unimaginable discipline and rigor will replay again and again. From here I can see their eyes, widening in fear and disbelief, as they fall during the most important performances of their careers, onstage at Thalia Mara Hall in the International Ballet Competition. And I am wondering why I keep coming back.

Jackson, Mississippi, is home to the American leg of the IBC. The three other host cities are Varna, Moscow, and Helsinki. Jackson is perhaps an incongruous addition to this roster, yet one of the world’s most celebrated ballet competitions has recurred here every four years since 1979. Thalia Mara deserves credit for this. Born in Chicago in 1911 to Russian immigrant parents, she began professionally dancing in the Twenties. She is most renowned, however, for her contributions to dance education: she published eleven books on the subject and founded the School of Ballet Repertory in New York City in 1947. Mara moved down South to Jackson in the early Seventies, on a mission to bring arts to a Mississippi recently integrated and still simmering from the turbulence of the preceding decade. This Jackson—archaic, backwards, remote—is what most seem to imagine when they hear of the city’s hosting of the Olympics of ballet.

The Jackson I know is defined precisely by the tulle and satin-filled drama of the International Ballet Competition. And these memories are inexorably tied to my grandmother, Rebecca Sykes, whom my brothers and I call Mama Becky. In 1979, years before I was born, my grandmother attended the very first IBC in Jackson; by the time I appeared she was a full-fledged balletomane with aspirations: “I just wanted a ballerina so badly in the family,” she told me. “And you were the first, and only, granddaughter for so long.” So Mama Becky stoked a rather pathological ambition in me from the beginning—encouraging my mother to enroll me in ballet class and introducing me, on my visits from Atlanta, to classical Russian composers like Tchaikovsky. I attended my first International Ballet Competition when I was ten. At her side, I was awestruck performance after performance. This was a different, lusher universe than the suburbs back home: one inhabited by the ibis-thin and tutu-clad, where beauty was just a veneer over the sweaty, bloody pursuit of perfection. It was thrilling.

That year, Mama Becky hosted a Cuban juror and a Peruvian dance teacher—two Marias—and by riding their coattails I was able to sit in on competitors’ private classes. I remember a Danish woman keeling over at the barre, falling to the floor, and tearlessly, wordlessly pounding the floor with her fists, her face contorted in rage. There was no explanation, only the quiet efficiency characteristic of ballet, as she was carried out of the room. Class continued. I didn’t see her on the stage again.

At the IBC there is an intoxicating cosmopolitanism as people converge from the world over, a haute sheen over interactions and introductions. Evening wear is appropriate. Stilettos click on the floor. Glasses clink as toasts are made. The euphonic hum of languages converging—English, Russian, Japanese, Portuguese. The per capita presence of dancers means there is a high density of beautiful people everywhere you turn. They come because of passion, drive, allegiance, belief. By being there with them, you are a part of this magic. I hoarded the beauty of this Jackson like a secret, unable and unwilling to elucidate for my friends back home. How could I describe what it was—this temporary, wispy loveliness?

I decided to return this summer, my first IBC in eight years. Mama Becky was delighted, though concerned that I had waited too long—procuring tickets would be a challenge, since they sell out months in advance. “Well, you’ll find a way. You always have,” she said, referring to my old habit of insinuating myself into the dancers’ strata, moving amongst them—including slipping un-ticketed into performances, where I blended into the shuffle and joined them in the dancers’ section, in the balcony. When I was fourteen, the year my grandmother remembers as the one I “decided to be someone else,” I sustained a vaguely European accent the whole time, introducing myself to everyone as an Estonian adoptee turned dancer. This was a bold move among a whole bevy of multilingual Europeans who could snap my story to twigs in seconds. But my commitment to character was unwavering and I never got caught. “We had a great time,” Mama Becky tells me now, “but I didn’t know what you would do next.”

In my fantasies leading up to the IBC, I had envisioned palling around with the dancers, making some friends, slipping again into their world. But something I hadn’t accounted for: I’m older than the oldest competitors now (the oldest members of the senior division are twenty-five, and their numbers are few) and the dancers, with their high buns and iPhones and knobby limbs, felt intimidatingly, bracingly young. This is a career of assured, brutal brevity where most professionals retire by their mid-thirties. So I’ve spent the week at a remove, watching from the crowd like everyone else. Maybe people see me and think I’m a former dancer, but probably they just think I’m my grandmother’s plus-one.

Dancing, pessimistically, can be said to inevitably, eventually erode one’s body. In transcending the limits of beauty, one must confront the limits of the body. The registry of de rigeur injuries is sobering: plantar fasciatis, dislocations, sprains, spondylosis. Female dancers’ feet, behind those pretty pointe shoes, are usually gnarled, bunioned, toenails split. There is even a foot injury called a dancer’s fracture—it happens most commonly on the fifth metatarsal, the outside edge, usually the result of a bad landing during a jump. Tonight, the final in two weeks of competition, is full of bad landings.

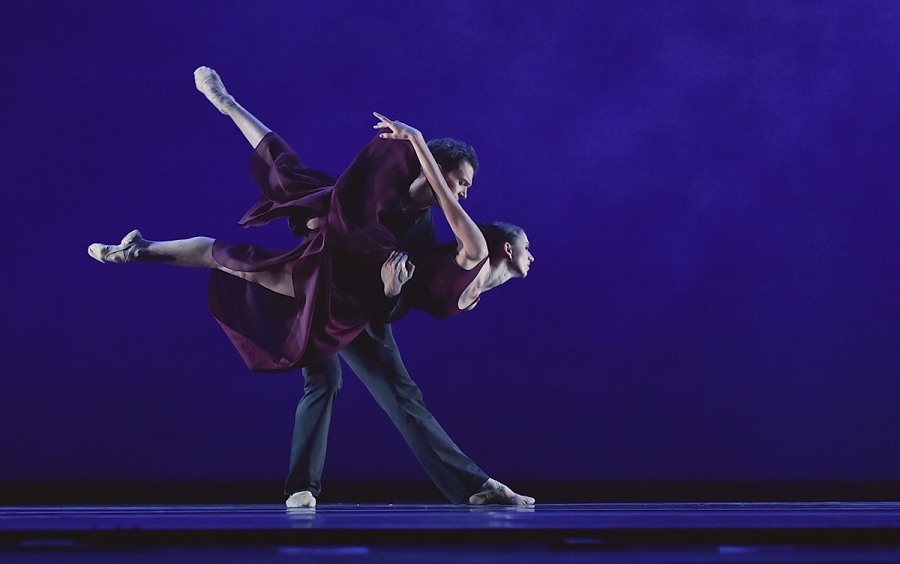

Sitting here, watching the dancers’ willful, determined displays of all their accumulated ambition, I experience a kind of somber awe—contrast to the giddiness I remember from years past. I focus on details and I can see from my front row perch what the general audience cannot. The smile of the ballerina as her supporting leg quivers when she extends into arabesque. The split second where the female dancer, in a pas de deux, locks eyes with her partner and something unspoken passes between them. The sheen of sweat on shoulders. The heaving of a male dancer’s chest after a virtuoso report of jumps. A new awareness of the competitors’ ascetic dedication to ballet settles heavily upon me.

As dancer after dancer takes the stage and performs their piece, the product of endless studio hours and exacting perfectionism, only to wobble a bit on a landing or to lose their balance during a turn, I hurt for them. It feels wrong. Ballet is a submission to impermanence, an art form that requires so much from its performers in exchange for just a few brief, bright bursts on the stage. It is the absolute devotion to something gorgeous with no assurance.

We get home late, past eleven, but there is much to talk about. The awards go out tomorrow. Mama Becky is troubled that her beloved Russian, who slightly stumbled, is out of the running. She’s seen every competition in Jackson since the inaugural, she reminds me. “I’ve never seen them give a gold to anybody who fell.”