Thrive

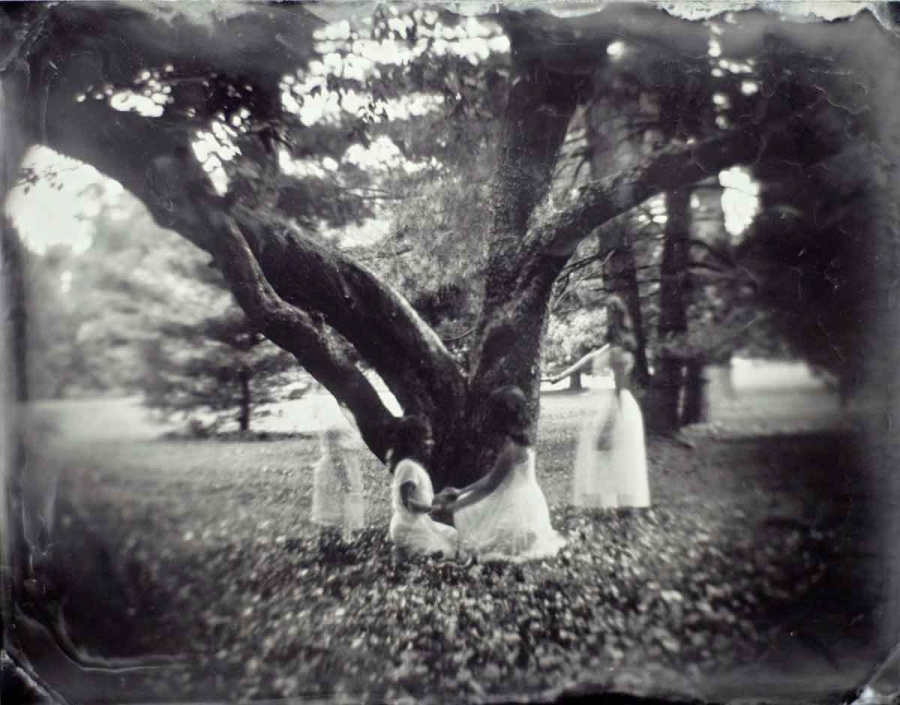

The history of the South is the South. And history is always with us—as present as you are, reading these words. As present as I mean to be as I type them. My South made me, in spite of itself. I love it because it is mine. But I’ll never know that it loves me, though I do belong to it . . . in it. I guess you’d say that sounds like slavery. In all the years I’ve watched television, in all the time it took me to get degree after degree, I’ve never heard anyone say slavery was a bad idea.

Slavery was a bad idea. It is also a bad idea to ignore the word we think most automatically when we think “South.” We may think “humidity.” We may think “hospitality.” More definitively, though, we see “South,” and we think “slavery.” I know because I’m a poet, and the poet in this South must say what historians and politicians and journalists and scientists neglect to say. Let me go further.

No sentence or idea should ever begin, “The good thing about slavery was . . . ” No pastor should be allowed to impart that through slavery some gained Christianity. No economist should pretend that all America got in exchange for slavery was cotton. No patriarch or matriarch needs to brag that the proof of black people’s strength is evident in their survival of slavery (especially since thriving—not surviving—is the actual goal of any life). I would like everyone to say, at least to one other person today, “Slavery was a bad idea” without adding an impulsive “but” at the end of the clause.

I live at the end of that clause. Let a man live in truth with you. In 2011, 46% of people diagnosed with HIV were young gay men living in the American South. Black men represented half of those cases. I am one of those black men. I want my South to want me alive. To agree that I do not deserve the death penalty for being or seeing or cussing or loving or smiling with my eyes wide open.

Today, in 2014, I just love how everything gets to be new. Criticism. Formalism. I hear sincerity is new. And, look at that, the South. I live in Georgia: 40 prisons. But I’m from Louisiana: 10 prisons. Well that’s just as many places to keep black and Latino people confined as there are states in the whole nation.

I will call the South “new” when it is new enough to lead—to admit that someone benefitted from slavery and that, today, someone’s descendants benefit from a system that looks a hell of a lot like slavery. Someone gains something from the system of incarceration that is big business in this country, and that someone ain’t most at risk of being thrown into prison. I am at risk.

I am at risk, and I know it because I look like the people at risk. In my generation, I am the only man on my father’s side of the family who has never been to prison. I am at risk until the South that made me acts as if my life is worth the value of any life.

I am a poet. I make theorems through language. I say, “Slavery was a bad idea.” Then I look at the land that made me and say, “If I know slavery was a bad idea, what else built on that evil can we tear down?” Let me go further.

You don’t get to be a poet without publicly asking questions that people say it’s rude to answer in public. Stay with me. What is the value of any human life? Now—what is the value of my life where I’m from, where I intend to thrive, where I’ve chosen to die?

Return to the Poetry in Place symposium.