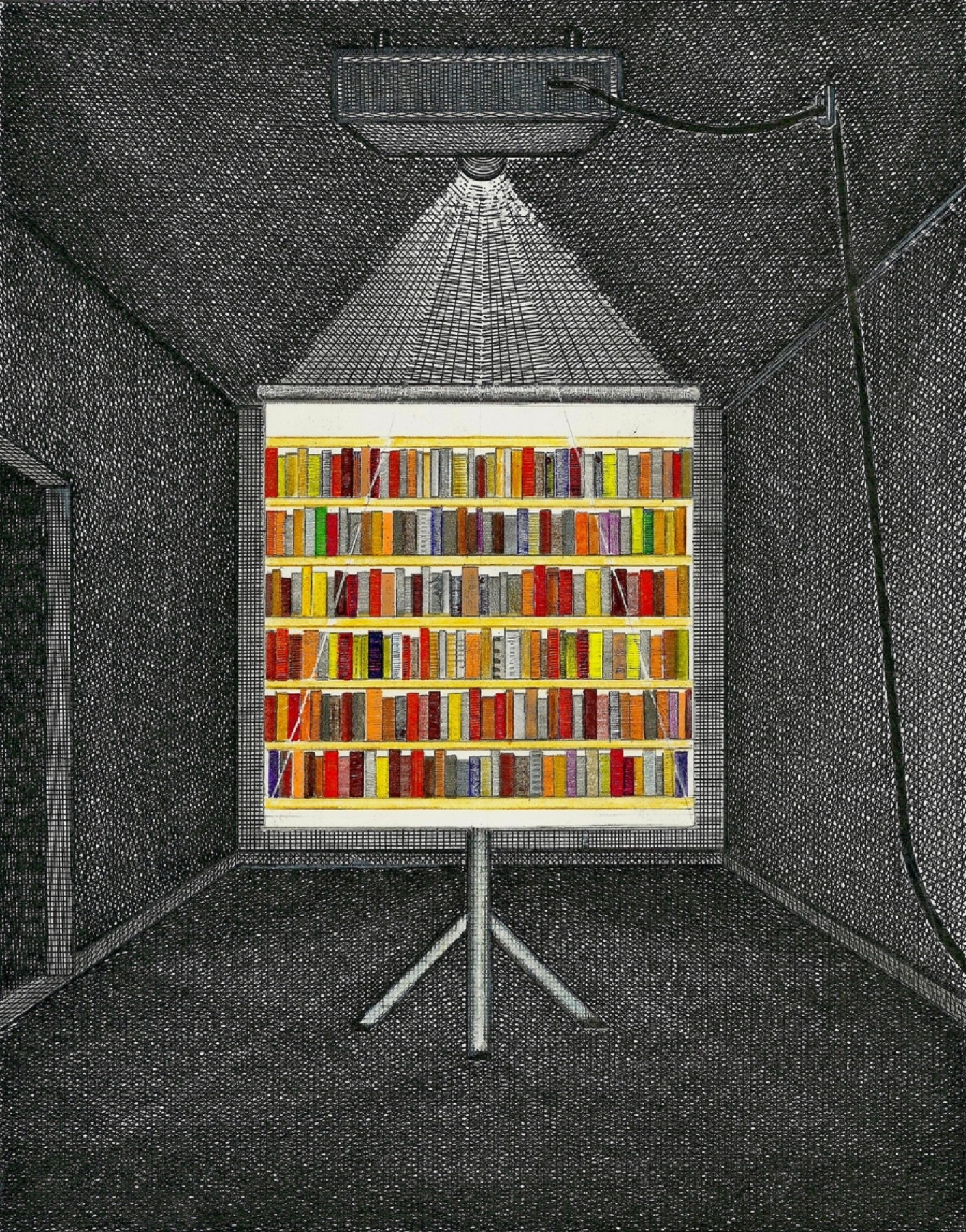

"Bookshelf Projection" by Fabian Hausermann

Where Books Fall Open

By James Seay

Some thirty or forty linear feet of my poetry library played a minor role in the movie The Portrait, starring Lauren Bacall and Gregory Peck. A minor role in a minor movie. It was directed by Arthur Penn, but it is no Bonnie and Clyde by any tally. That saddens me, as I was a Penn fan and I had a pleasant talk with him on the movie set, mainly about our mutual friend, the poet Richard Wilbur.

I say linear feet because that is apparently the metric by which prop managers deal with books. Once they hear that you have books and determine that those books have the right look for the movie, they negotiate to rent enough of them to fill the designated shelf space. A few linear feet of my poetry books made the final cut in one scene, and a linear inch appears in Peck’s hand as he descends the stairs in another scene. He tells Bacall that he has found a misplaced car insurance policy tucked away in a book of Richard Wilbur’s poems.

Aware myself that things get misplaced in the world, I had inventoried my books before sending them out to bear witness for literature—and bring home revenue for additional books to extend their sovereignty on my shelves.

A book of Whittier’s poems, nicely bound, the pages gilt-edged, did not make it back home. I cannot say that I felt this loss keenly—in the way, say, I would feel the loss of a book inscribed to me by a fellow writer—because Whittier is not one of my favorite poets. Some of his poems have historical value for me, and I’ve always liked the sound and incremental syllable-spread of his name. John Greenleaf Whittier. What the early rhetoricians called a rhopalic. Friends, Romans, countrymen. But Whittier’s sentimentality has kept him generally unvisited on my bookshelf.

Nonetheless I did feel the loss of the book, owing to the fond memory I have of my initial engagement with the physical book itself—and to the situational irony of that experience. I bought it in a used book store in Nags Head on the Outer Banks of North Carolina during a summer vacation. When I took the book from the shelf and tested its heft, it fell open to “Snow-Bound.” Standing there beneath a ceiling fan that barely stirred the humid coastal air in the room, I skimmed Whittier’s once-famous winter idyl. The poem renders in nostalgic measures a family’s experiences during a winter storm that raged for three days in rural Massachusetts when the poet was a boy.

You will recall, or your grandparents will recall, that the snow-bound poet and his family are drawn into even closer intimacy as they face the chill embargo of the snow. They go about their nightly chores—bringing in firewood, littering the stalls with hay, feeding the livestock—and then they gather around the hearth-fire to share stories. There is no question but that these storytellers have a snug relationship with the Angel of the backward look. Nostalgia reigneth.

Closing the book and holding its spine in my palm, I could see along the length of its fore edge a thin line of discoloration and wear that marked the location of “Snow-Bound.” Pilgrims, tourists, whoever under whatever banner, they had collectively worn a path to the same place at the altar rail.

This set me to thinking of books that I have returned to over the years and how any one of them could also be expected to fall open, as did the Whittier, to a favored passage or poem or story. Likely many of your own books would fall open in consonance:

Lend me a looking-glass; / If that her breath will mist or stain the stone, / Why, then she lives. But Cordelia is of course "dead as earth."

”There’s a certain Slant of light, / Winter Afternoons— / That oppresses, like the Heft / Of Cathedral Tunes— / Heavenly Hurt, it gives us— / We can find no scar, / But internal difference, / Where the Meanings, are— / None may teach it—…

…I was a flower of the mountain yes when I put the rose in my hair like the Andalusian girls used or shall I wear a red yes and how he kissed me under the Moorish wall and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.

There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names of places had dignity. Certain numbers were the same way and certain dates and these with the names of the places were all you could say and have them mean anything. Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates.

Proust’s tea and madeleines; Odysseus’s homecoming, he in disguise and his dog Argos’ tail thumping in recognition before breathing his last; Achilles’ shield; Auden’s take on the implications of that shield, That girls are raped, that two boys knife a third, / Were axioms to him, who’d never heard / Of any world where promises were kept, / Or one could weep because another wept. Eudora Welty’s “Petrified Man,” her character who asks Funny-haha or funny-peculiar? How Milton’s serpent approaches Eve with tract oblique. The cunning of indirection. On and on, books falling open, the canon ever changing, each register inevitably of the reader’s time and place.

Mine was not a bookish family, though I could count on a new Hardy Boys mystery every year under the Christmas tree. And I cherished the slipcase edition of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer that my Uncle Jack sent me from Marshall Field’s in Chicago. In search of more such adventures, I became a regular at our town library, which was housed in a sweet little church that the local Episcopalians had outgrown and given to the town. And so my engagement with books came to be informed by the light that transfused softly through the body of the Virgin Mary, the Dove of Peace descending upon her in Annunciation, Christ in Gethsemane, O my Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me. Christ laboring to Golgotha, And he bearing his cross went forth into a place called the place of a skull. The Resurrection, O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory? All in the stained glass of the windows surrounding me.

As I was innocent of the concepts of faith and salvation beyond mere rote, those stained glass representations had only a nominal claim on my mind. But the lucency, the transformed quality of the light itself coming through the windows, made for a sense of magic and the ineffable. Sitting at my library table, surely I must have sensed that the light falling on the book before me was enhanced by its union with mystery and miracle, though I could not have given voice to any such notion.

In my hunger for adventure I typically gravitated to the table beneath Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. With Nebuchadnezzar’s fiery furnace behind them, they were in league with the Hardy Boys and dangers evaded, whether providential or by Boy Scout preparedness. The library tables themselves, and the chairs complementing them, came out of the furnace of World War II. They had been made by soldiers of Rommel’s Afrika Korps interned in a POW camp, Camp Como, in my home county in Mississippi. Some of the prisoners were put to work in the cotton fields. Others made the clunky tables and chairs which I now realize were simulacra formed in wistful dreams of taverns in Bavaria.

In addition to the name of the deft and relentless Rommel in my mind was the name of Isabel Swann. Isabel lived in my hometown and had worked in the canteen of the POW camp. She began an affair with one of the German soldiers, a former Panzer tank driver. You would think that she would have taken up with one of the Desert Fox’s officers, given that they had less supervision and thus more opportunity for an assignation, but instead she found romance with a tank driver who was assigned to a Singer sewing machine in the camp. He repaired uniforms, let out pants, and such. He was reassigned to a camp in Idaho, digging potatoes, beets, and onions. Isabel was heartbroken and became known in town as one who “had been up there at Como fucking Nazis.”

And so I sat in my chair under the silent furnace of Nebuchadnezzar, a book open before me on one of the tables crafted by Rommel’s imprisoned Panzers, reading my way into the future. That chair and table, the hagiography of the windows made simple in annunciations of flushed light, the dove descending, Mary in blue, Isabel and her abandon, a treadle sewing machine, all are a permanent inscription in my formation as a reader. One could speak of palimpsests on which our journeys as readers continue to be recorded, layer upon layer. When gathered together in bound signatures and tested for heft, where will they fall open?

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.